American View

Feature

Transforming the Rabbinate Over 50 Years

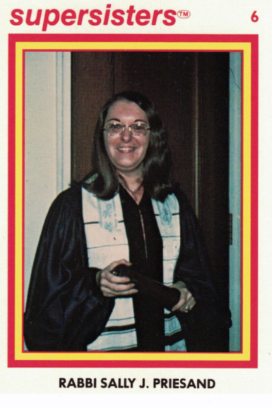

When Sally J. Priesand became the first woman to be ordained by a rabbinical seminary, at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion on June 3, 1972, some hoped and others feared that it would start a revolution.

Instead, it has been an evolution.

Over the past five decades, the rise and integration of women into the rabbinate has transformed many aspects of Jewish life.

“We’re at a tipping point where we have as many women in the active rabbinate as we do men. It’s more or less equal,” said Rabbi Hara Person, president and CEO of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the professional organization of Reform rabbis known as CCAR. Of the group’s 2,200 current members, she said, 810 identify as female.

“Women’s voices and ideas and creativity have become central,” Person continued. “At one time, it was marginal, maybe even discounted or minimized. Today, women are in leadership and decision-making roles. Women are out in the front, leading the rabbinate.”

In Israel, Breaking Barriers in the Orthodox World

More than 1,500 women have been ordained across the Jewish world in the past 50 years, according to a survey of leaders of all the movements, from Orthodox to Renewal. Female scholar-rabbis now teach at and, in some cases, run rabbinical schools. Through books and other platforms, they have broadened the understanding of Jewish history, ritual and theology. Gender-inclusive language is now the norm in all prayerbooks in the mainstream liberal denominations. Women in the rabbinate have also raised questions pertinent to all clergy about issues like work-life balance.

Yet serious challenges remain, and, for some, progress has been too slow.

Many pioneering rabbis say that the constant surveillance and commentary about what they wore; verbal digs from male rabbis, board members and congregants; and, sometimes, outright verbal, physical and sexual harassment remain bitter memories.

Nasty remarks were frequent, recalled Rabbi Amy Eilberg, who in 1985 became the first woman ordained by the Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary. She remembers comments like: “Oh, do I get to kiss the rabbi?” and “The rabbi is wearing open-toed shoes.”

Eilberg, now 67 and living near San Francisco, moved to chaplaincy and pastoral care after one year with a congregation and has since focused on providing spiritual direction and teaching mussar, or Jewish ethics.

Though inappropriate remarks and behavior continue, it has diminished in recent years, according to many in the field. As Person noted, “Women are much less likely to take it today than they were at one time.”

“Culture has changed. The putting-down remarks, the microaggressions, those have become unacceptable. They were rampant in the early years,” said Pamela Nadell, professor and Patrick Clendenen Chair in Women’s and Gender History at American University and author of Women Who Would be Rabbis: A History of Women’s Ordination, 1889-1985.

Today, the non-Orthodox movements are paying new attention to sexual harassment and misconduct in the rabbinate, including misconduct directed at female rabbis and rabbinical students. A 2021 report from the Reform movement’s HUC found a history, going back decades, of sexual abuse, harassment and discrimination by powerful leaders, including presidents and chancellors, against female students.

WATCH NOW: CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF FEMALE RABBIS

A virtual event featuring Rabbis Sally Priesand, Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, Amy Eilberg and Sara Hurwitz, all of whom made history by becoming the first ordained rabbis in their respective denominations.

For its part, the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly is in the process of conducting its own study, said Rabbi Jacob Blumenthal, CEO of both the RA and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the denomination’s congregational arm. Last fall, the RA for the first time began publishing the names of rabbis sanctioned for ethics breaches, shifting the culture of secrecy that until now protected rabbis guilty of sexual misconduct.

Today, female rabbis face discrimination primarily when it comes to pay disparities between men and women as well as in their quest for top congregational jobs and for equitable family leave policies, experts say.

A study by the Conservative rabbinical body in 2004 found a $40,000 difference in mean compensation between male and female rabbis. Fifteen years later, a 2019 study showed that the largest gap remains only for newly ordained rabbis, with women fresh out of seminary earning an average of 18 percent less than men. The study, which is not available to the public though selections from the report were shared with Hadassah Magazine, found that among rabbis with five to 10 years of experience, men make an average of 3 percent more. The small number of women serving the largest congregations actually earn slightly more than their male colleagues—on average, $170,500 compared to $168,700.

In the Reform movement, an across-the-board 18 percent wage gap exists for women, according to Rabbi Mary Zamore, executive director of the Women’s Rabbinic Network, a 600-member organization that was founded in 1990 to advocate for female Reform rabbis. She noted that in the past three years, “we’ve seen a nice narrowing [of the wage gap] for assistant rabbis and senior rabbis at the larger congregations.”

Meanwhile, the Reform Pay Equity Initiative, which was formed five years ago by 17 organizations, is working to create a uniform family leave policy to be used in all rabbinic contracts, rather than have each negotiated individually, which often works to the rabbi’s disadvantage.

Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso started rabbinical school at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in 1969 as part of its second class because, she said, the institution’s president at the time feared that admitting a woman in its inaugural year would be too controversial. During her time at RRC, Sasso, now 75, wanted to research women in Judaism, but “there were no books” on the subject, she said. “When I asked questions or was asked to speak about women and Judaism, I could find no material.”

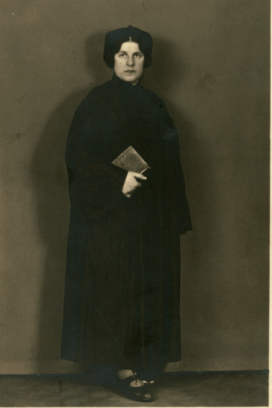

As the number of female rabbis has grown, their intellectual and creative contributions have also expanded. Libraries are now filled with volumes written by female rabbis and scholars, from Torah commentaries to books on women in Torah and long-forgotten pioneers who have been rescued from the ash heap of history. Among those neglected innovators is Regina Jonas, widely considered the first ordained female rabbi, who received a private ordination in 1935 because the German seminary where she had studied refused to grant her semicha. Jonas was murdered in Auschwitz nine years later. (Watch this powerful short video about Regina Jonas.)

Change in the religious realm happens slowly, noted Sasso, who was ordained in 1974 and served for 36 years as co-rabbi with her husband, Rabbi Dennis Sasso, at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis. “When everything around us is changing and topsy-turvy, and the ground is not firm, we assume religion will be the place we can escape to,” she said. “People are less comfortable with rapid change in religion. That’s why women doctors and lawyers were accepted before rabbis.”

Another major issue for female rabbis today, said Nadell of American University, “is the challenge that American women face in all professions: How do you balance family life and an extremely challenging career in a country that does not have adequate childcare?”

For some of the trailblazers, family life didn’t seem like an option, and becoming a rabbinic leader came at a cost.

“I always thought I would get married and have children and planned a nursery next to my study,” said Priesand. But once she began working in a synagogue, “I realized I just couldn’t do it. I could never have both a career and a family and do both well. So I chose my career.”

“I made decisions based on what was best for women in the rabbinate, not necessarily what was best for me,” Priesand continued. “I was very conscious of the fact that people were judging women in the rabbinate through me.”

Now 75, Priesand is retired from Monmouth Reform Temple, the New Jersey synagogue she led for 25 years and where she continues to attend services regularly. Her first rabbinic job was at the prestigious Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in Manhattan, where she worked for seven years as assistant and then associate rabbi.

Finding a position as a senior rabbi, however, was extremely challenging, recalled Priesand. “People just weren’t ready yet” for a woman to fill the senior position at a large synagogue.

Today, the job of being a rabbi is changing, at least in part because of female rabbis advocating for greater flexibility.

“Women have helped all colleagues with issues of institutional culture,” including work-life balance issues, said the Conservative movement’s Blumenthal. “These aren’t just priorities for women, but often women speak in a stronger voice, and it’s a help to our entire profession. There is no one way for women or men to be a leader but notions of leadership are changing because we have a more diverse field of rabbis.”

That diversity has expanded in recent years to include rabbis of color, rabbis with disabilities, openly gay rabbis and transgender and non-binary rabbis.

In part because of work-life balance concerns, rabbis—both men and women—are increasingly opting for careers as educators, Hillel directors, chaplains and nonprofit leaders rather than pulpit positions in congregations.

It is different today than it was in the time of Reconstructionist founder Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, when the expectation associated with becoming a pulpit rabbi meant “a rise to status, maybe even a national voice, along with significant pay,” said Rabbi Deborah Waxman, CEO and president of Reconstructing Judaism, which includes the Reconstructionist rabbinical seminary and its congregational arm. “I don’t think that’s the future [young rabbis] necessarily want or expect.”

The first women in the major liberal denominations paved the way not only for female rabbis worldwide but also for Modern Orthodox women to join the rabbinate—a much newer phenomenon.

Holy Sparks: Celebrating Fifty Years of Women in the Rabbinate

“Seeing women as rabbis became more normative and allowed young Orthodox women to see themselves in that role,” said Rabba Sara Hurwitz, 44, president of Yeshivat Maharat, which she co-founded with Rabbi Avi Weiss of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale, who ordained her privately in 2009. “This allowed us to begin dreaming what was possible.”

Since its first class in 2013, the women-only Yeshivat Maharat, which is an acronym for Hebrew words meaning a female leader of Jewish law, spirituality and Torah, has ordained 49 women, with each deciding her own title. They include rabba, rabbanit, maharat and rabbi. Nine more women are slated to be ordained in June. Most work as educators, chaplains and in other non-pulpit roles, though a few serve in assistant and associate positions at synagogues.

Maharat Ruth Friedman, for example, was in Yeshivat Maharat’s first cohort and serves as clergy at Congregation Ohev Shalom-The National Synagogue in Washington, D.C. Rabbanit Hadas Fruchter is the only Yeshivat Maharat graduate to lead her own congregation, the South Philadelphia Shtiebel, which she founded in 2019.

For all the challenges faced by women in the rabbinate, the rewards have been great, pioneers agree.

“I’ve seen tremendous change,” said Eilberg, despite the fact that there remains “understandable outrage that women are still being paid less and respected less.” Just because there have been female rabbis for 50 years, she added, “doesn’t mean sexism has been eradicated. It’s alive and well.”

At the same time, she said, “there was never any question about whether what we are doing is meaningful.”

There are very few careers, Priesand agreed, “where you can touch people’s lives in such meaningful ways.”

READ MORE:

Then and Now: The ‘Four Firsts’ ordained in their respective denominations weigh challenges to the Jewish community

MORE STORIES:

Building Community Far From the Madding Crowd

Envisioning the Rabbinate Through a Different Lens

Holy Sparks: Celebrating Fifty Years of Women in the Rabbinate

In Israel, Breaking Barriers in the Orthodox World

Blu Greenberg Is Still Advocating for That Rabbinic Will

Debra Nussbaum Cohen, author of Celebrating Your New Jewish Daughter: Creating Jewish Ways to Welcome Baby Girls into the Covenant, is a journalist living in New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Carol Steinfeld says

This will be a wonderful program to watch. I saw them in Indianapolis a number of years ago in Indianapolis. I am a member of Rabbi Sandy’s synagogue and will be interested in hearing the differences since then and how things are now. THank you for bringing this Hadassah program.

Shoshana says

Regarding the article about Rabbanit Henderson and her Toratah project (switching the male and female characters in the Torah), I am appalled that she would do this and that your magazine would even consider printing such chutzpa and a shandeh! One cannot change our history! History has happened. It’s our rock as Jews; it gives us credence that we existed and still exist today. We learn from our predecessors’ role models such as Chana how to pray with our lips when she begged Hashem to bless her with a child! To dare write that Moses was a woman is defacing our history, creating confusion, and spreading a lie to people who don’t know any better!

The Torah is not a fantasy book in which characters are interchangeable nor is it immutable. There was ONE Torah given at Mt. Sinai to ONE people. The Torah we read today is the same and original version, revealed directly by G-d through Moses. It has never and will never be revised like a second edition! Our interpretation may be different across the spectrum of Jews; however, one cannot alter G-d’s direct, holy and sacred transmission.

The future can be shaped and we can learn from the past but one cannot change history!

Sarah Rousso Lascar says

I’m reading this article after attending my nephew’s wedding. This young man comes from a family of both Sefardic and ashkenazi heritage. His great grandfathers were Hazanim and Rabbis in their respective European communities.

They lived in neighborhoods that oftentimes were mixed yet were respectful of diverse religious affiliations. The communities existed for hundreds of years while maintaining and following traditional norms. While living in more modern societies that oftentimes had discrimination towards our Tribe modifications were adopted to be part of the norm, in order to fit in. Nevertheless, our ethical Biblical laws haven’t changed. Some Talmudic, Mishnaic laws written by Rabbis have modified observances by both Sephardic and Eshkenazi Jews. And the customs to observe life cycle events holidays and Shabbat originate in the location of the family, specifically where they came from. Cuisines, rituals, religious objects were all influenced by the ambience and surrounding communities that Jews adapted and adopted. As an egalitarian woman Sefardic Rabbi I open the gates to future generations who will carry on the traditional customs of Sefardim, the remnants of the Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492, the year Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue. Shabbat Shalom