Hadassah

Feature

Moments from a Century

Defining experiences from Hadassah Magazine writers and contributors:

Home Free

From 1964 to 1971, I wrote the column “Diary of an American Housewife” for Hadassah Magazine. In April 1971, I experienced a Passover week that made the paradox of Israel more haunting and poignant than ever. Here’s what I described: Soldiers manning underground fortifications along the Suez Canal. People stampeding Jerusalem’s Fifth International Book Fair in such throngs that the officials gave up trying to sell tickets. The opening of a $4-million museum in Tel Aviv. Celebrating the Seder near the Western Wall with newcomers from the Soviet Union. Black Panthers (sons of Jewish immigrants from Arab lands) meeting with Prime Minister Golda Meir and demanding not only better housing and jobs but the right to serve in the Israeli Army. Leonard Bernstein conducting the Israel Philharmonic. Meeting a planeload of Russian Jews.

“I have seen every exodus into Israel since the birth of the State—Yemenites, Iraqis, Moroccans, Poles, Algerians, Bulgarians, Romanians, Persians, Indians, Russians,”

I wrote in the June 1971 issue. “The people wear different costumes. They have different appearances. But for all of them this is the moment. They are home. And free. This is the meaning of Israel.” —Ruth Gruber

Gruber is a pioneering woman journalist.

Remember the Alamo

Some time ago, I wrote a Purim piece for Hadassah Magazine in which I lamented the lack of Ashkenazic Jewish place names, for example, Schwartz’s Gap, in the American West, and I wondered whether there had been a minyan in the ill-fated Alamo. To my surprise, several months later, I received a letter from a member of the Texas Jewish Historical Society informing me that eight Jews had been in the Alamo. Almost a minyan but not quite. Three years ago, during a visit to Spain, when I wandered into the Ramban Institute in Girona (Ramban’s hometown), I received professional courtesy as I am a gabbai of the Ramban Synagogue in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem. As I reflected on the Expulsion from Spain and its far-flung consequences, I wondered about “the other side” at the Alamo. Might Santa Anna’s victorious Mexican army have included a minyan of Conversos or Chuetas? Or, at least, two to complement their eight coreligionists inside? If not Schwartz’s Gap, Ibn Gabirol’s Arroyo? Perhaps another letter will come my way. —Allen Hoffman

Hoffman is a fiction writer who lives in Jerusalem.

The Wall

After I left the staff of Hadassah Magazine, I was invited by the magazine to cover the International Conference for the Empowerment of Jewish Women, held in Jerusalem in December 1988. The conference brought together women from all streams of Judaism and all corners of the Jewish world. During the course of the conference, an interdenominational group of women—among them, Francine Klagsbrun and Rivka Haut—launched the idea of bringing a Sefer Torah into the women’s section of the Western Wall for a halakhic women’s prayer service. I was among some 70 women at the Kotel for that historic davening and Torah reading, which was met by jeers and shouts from the men’s section and objections from some haredi women. It was an extraordinary moment, and thanks to Hadassah Magazine, I witnessed the birth of Women of the Wall. —Roselyn Bell

Bell worked at Hadassah Magazine from 1978 to 1988. She is currently editor of the JOFA Journal.

Oral Tradition

I’ve been enjoying Hadassah Magazine for 47 years. I have watched it change in size and layout, but for all these years, I’ve eagerly read the articles.

I was installed as region president in 1989, holding my first board training immediately afterward. I wanted to open with something inspirational and also teach my board how to share materials from the magazine, so I read a brief article to them and then asked if anyone knew where the message came from.

The message moved all of them—but none recognized the source, though they had read the magazine. Reading an article is different than hearing it read out loud. Even seeing it in a local bulletin, taken out of context, makes it “new” and is a wonderful way to share exciting information. Hadassah Magazine articles remain timely and challenging. Share the articles, share the recipes and know that I’m thinking of you when I work on my message in the magazine! —Marcie Natan

Natan is national president of Hadassah.

Tea and Wisdom

When I was 15 years old, I had the privilege of having published in Hadassah Magazine a piece about my experiences on a Jewish teen tour of Poland and Israel. Many connections resulted from that article, but my favorite was the opportunity to meet an esteemed Hadassah reader (and contributor): Walter Eytan. He wrote to me through the magazine and suggested that if I were to return to Israel, he would love to meet me. I was 15; it did not occur to me to try to research this person in advance. On a family trip to Israel the following summer, I contacted him, and my parents and I were invited to tea.

As I only appreciated later, this was the equivalent of having tea with Thomas Jefferson. Eytan, a former British intelligence code-breaker and Oxford don, was the first director-general of the Israeli foreign ministry in 1948. He led the armistice negotiations after Israel’s War of Independence, was Israel’s ambassador to France in the 1960s and later ran the Israel Broadcasting Authority. In his gorgeous home in Rehavia, both my parents and I were gobsmacked by this man’s regal 83-year-old presence, his endless erudition, his almost comical articulateness and the thousands of books in many languages lining the walls behind him as he sipped his tea. He told us that day that he had largely given up reading the foreign press, that the quality of Le Monde and The Guardian and The New York Times were no longer worthy of his time or intellect. “The only English-language publication worth reading,” he told us with absolute authority, “is Hadassah Magazine.” —Dara Horn

Horn’s latest book is A Guide for the Perplexed (W.W. Norton).

Looking Deep

In the almost three decades of contributing to the “Israeli Life” column in Hadassah Magazine, I have learned the DNA of a people that laughs at their founders’ idealism yet measures themselves against it; rebels against but also embraces Jewish values.

I have visited student villages being created on the footprints of defunct moshavim, in a return to Israel’s collective ethos; seen young people reach out to work with at-risk youth; and secular youth reconnect to Jewish texts in egalitarian yeshivot and pre-army mekhinot, creating rock music suffused with biblical references.

I also observed how, facing existential dilemmas, Israel must balance defense with human rights. And the magazine allows a portrayal of the human condition in all its complexity—the Israeli-Arab conflict, the reaction to Iran and the security fence that disrupts the lives of Arabs while saving Israeli lives.

During the disengagement from Gaza, I recorded the voices of women in Gush Katif, with whom I disagreed ideologically but could not help admiring. On assignment for the magazine, I have been encouraged to help readers understand Israel more deeply—with professionalism and compassion. —Rochelle Furstenberg

Furstenberg is a freelance writer living in Jerusalem.

Love and War

In 1973, as my family and I prepared for a vacation in Israel, Hadassah Magazine asked me to do a story on a summer wedding to be held in Rosh Ha’ayin. The bride, a 19-year-old American and a Young Judaea Year Course graduate, was to be married according to the traditions of her groom’s Yemenite family in a celebration spanning two evenings, the first devoted to the henna ceremony and the second to the formal marriage beneath the huppa.

My husband and I joined the guests watching as the henna paste, a mixture of herbs beaten into a fine green cream, was placed on the hands of the bride. For this ceremony, the bride wore pantaloons and a gown of shimmering gold and black and a lovely matching hood. Friends and relatives showered her with necklaces, bracelets and earrings, all on loan according to the Yemenite custom that holds that every bride be adorned. However, I noted one untraditional item of jewelry. Pinned to the neck of her dress was the Hadassah life membership pin she had asked for and received for her 16th birthday back in Long Island. Hadassah and its Zionist message were represented on this brightly lit rooftop, fragrant with incense and permeated with the music of a culture that dated back to the days of the Queen of Sheba.

The beautiful photograph of the bride was scheduled to be the cover of the November 1973 issue. But because of the Yom Kippur War, the cover instead showed a tender farewell between a soldier and his fiancée in the plaza before the Western Wall. The article entitled “A Wedding in Israel” still appeared in that issue, a reassuring affirmation that, war and tragedy notwithstanding, the joy and promise of a state in which many people became one nation endures. As does the always realistic and optimistic message of the wonderful publication that has been integral to my professional and Zionist life for more than half a century. —Gloria Goldreich

Goldreich’s The Bridal Chair: A Novel (Sourcebooks) will be published in March 2015.

Three-Corner Breakthrough

One day in 1979, my friend, the as-yet unknown Wolf Blitzer, called me. “You’ve just hit the Jewish jackpot,” said Wolf, then Hadassah Magazine’s Washington correspondent. “What do you mean?,” I asked. “There is a two-page excerpt in Hadassah Magazine from your new book,” he responded. “It’s all about hamantaschen.”

Hamantaschen? For years I had been pitching food stories to no avail to Hadassah Magazine’s then-editor Jesse Zel Lurie. He told me repeatedly that he did not want to feature food in the magazine. So I called him to ask why the sudden turnaround with an excerpt from The Jewish Holiday Cookbook. He paused, then said in his gruff Brooklyn accent: “Well, I like hamantaschen, I like Purim and I like you.”

That was my first but not last food article I wrote for Hadassah Magazine. And, as Wolf said, it was the one that put me on the map. —Joan Nathan

Nathan is working on her 11th cookbook, King Solomon’s Table (Knopf).

Papers, Please?

“I hate doing things this way,” said the Jewish Agency man who was helping arrange my trip to Samarkand. It was July 1992. In June, Hadassah Magazine’s executive editor, Alan Tigay, had passed through Jerusalem and asked me for article ideas. Half-seriously, I suggested a travel piece on Samarkand in newly independent Uzbekistan. Completely seriously, Alan said, “I need it by August.”

There were no scheduled flights from Israel. Luckily, the Jewish Agency agreed to let me take the biweekly charter to Tashkent that picked up immigrants. A day before my flight, though, I had no visa. The former Soviet, now Russian, embassy in Tel Aviv could issue valid papers, but wasn’t supposed to.

The Jewish Agency man’s wife, originally from Soviet Georgia, knew the wife of a Georgian official at the ex-Soviet Embassy. Phone calls were made. Holding 280 shekels in a sealed envelope, I arrived the next morning at the embassy. It was closed—to all but friends of the Georgian. At noon I had the papers. That evening, I boarded the near-empty plane to Uzbekistan. —Gershom Gorenberg

Gorenberg’s latest book is The Unmaking of Israel (Harper Perennial/HarperCollins).

Giving Life

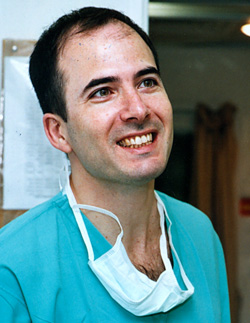

It was 2004 and deep into the second intifada. Neurosurgeon José Cohen was new to Hadassah’s medical center but I had heard about him. “He reaches into the grave to pull people back,” they said. I had been writing for Hadassah Magazine about the hospital for 15 years by then and thought: “Many here can claim that.” But then

I met José (above) and he told me about a recent patient, a soldier shot in the neck by a Hamas terrorist. The soldier was dying, blood gushing from his wound. With no time for surgery, José inserted a $1,000 endovascular coil into the young man’s leg and guided it through his

vessels to seal the ripped vertebral artery. The bleeding continued. He inserted another, then another.

“It took 16 coils,” he told me. “We just kept putting them in.” Three months later, the young man was back in Hadassah Hospital to hold his newborn daughter. The Argentinean-born surgeon’s account has stayed with me—riveting in itself and a symbol of what the medical center has become to me and to Israel. —Wendy Elliman

Elliman, a British-born freelance writer, has lived in Jerusalem for 40 years.

The Missing Issue

Hadassah Newsletter was published for many years under the competent editorship of Shulamit Schwartz Nardi. I had written several articles for it.

In the spring of 1947, the United Nations convened a Special Assembly to decide the fate of Palestine to replace the British Mandate. Hadassah felt a need for a newspaper that could bring reports from the United Nations and Israel into Hadassah homes when they happened. The newsletter had been printed in a large shop in Illinois that specialized in organizational papers. Two or three weeks elapsed between the time that Shulamit put the issue to bed in New York and she received a copy from Illinois.

Hadassah signed a contract with me to edit an eight-page tabloid newspaper beginning in October 1947. I started work the month before. With one assistant, the venerable Rebecca Jaffe—who was always Miss Jaffe—I put out the first issue of the tabloid Hadassah Newsletter dated October 1947. Here is the mystery: What happened to my first issue? Why was there not a single copy available when we bound the copies at the end of the year? Had a collector of first editions acquired every copy of the first issue in the morgue?

The first issue must have had a report from the United Nations. The Political Committee, but only by a simple majority, had submitted to the assembly for its approval by the necessary two-thirds majority a resolution partitioning Palestine into two states: one Jewish and one Arab.

Tension was high at the United Nations and in the capitals of small countries, such as the Philippines and Haiti, which had voted against the resolution in the Political Committee.

A two-thirds majority was achieved on November 29, 1947, and the December issue of Hadassah Newsletter carried a thrilling banner headline across the front page: “UN VOTES JEWISH STATE.”

The Arabs rejected their state—they wanted all of Palestine—and they attacked their Jewish neighbors. There have been 64 years of wars and ceasefires while the Jewish state, named Israel, flourished.

But I will never know what happened to my first issue. No one has a copy. —J. Zel Lurie

J. Zel Lurie was editor of Hadassah Magazine from 1947 to 1980 and publisher from 1980 to 1984.

Both Sides Now

I have so many memories of covering Hadassah conventions, stretching from the early 1990s to 2010. Thanks to Hadassah Magazine, I’ve heard everyone from Hillary Rodham Clinton to Shimon Peres to the late Wendy Wasserstein. Interviewing former Charlie’s Angel Jaclyn Smith in 2008 on her work for breast cancer awareness stands out in my mind because I never imagined someone so gorgeous could be so modest and considerate. My dad had died about a year earlier, and I was able to tell her how much he admired her. Rabbi and author Harold Kushner is the most interesting person I ever sat next to at a Hadassah banquet. By the end of dinner, we knew each other’s life stories.

During Washington, D.C., conventions, every politician and diplomat in town wanted to speak to Hadassah Magazine. Some, like Anthony Weiner, have not lived up to their early promise. Others, like Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL), have gone on to big things. At the last convention I attended, my novel Rich Boy was about to come out, and I suddenly found myself on the other side of the podium, fielding questions. —Sharon Pomerantz

Pomerantz is a novelist, short story and nonfiction writer who teaches at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

A Higher Authority

May 1991. One of the first people I called on my arrival in Jerusalem was Wendy Elliman, a longtime correspondent for Hadassah Magazine. She mentioned that she was working on an embargoed story—one that could not be revealed to the public before a specific date—on the airlift of Ethiopian Jews to Israel.

She was covering the story for United Jewish Appeal and said if I wanted press credentials for the military side of Ben-Gurion Airport, I had to call Rafi Rothstein in New York. That was good news, since Rafi was a friend. When I called Rafi and told him what I wanted, the first thing I heard was, “You have to talk to God.”

It turned out he was referring to Gad Ben Ari, the Jewish Agency official handling press in Jerusalem. I contacted Gad, got my credentials and spent the next two days shuttling between Ben-Gurion and various absorption centers. The scenes of immigrants streaming down the stairs of commercial airliners or out of the rear hatches of transport planes were mesmerizing—young and old; mothers carrying babies in their arms; men carrying elderly parents on their backs; onlookers from the media, airport personnel, government and army smiling, laughing and crying. It was like watching a scene from the Bible.

To me, it was the most intense view I ever had of Israel’s reason for being. In two days, more than 15,000 Ethiopian Jews arrived. It was the best story I ever covered, for Hadassah Magazine or any other publication.

When it comes to faith, I’ve always liked the expression, “God is in the details.” After that experience, I understood that He is also in the pauses. —Alan M. Tigay

Tigay is executive editor of Hadassah Magazine.

The Covenant

One article I labored over for the October 1978 issue dealt with the rising number of Jewish singles in their thirties and forties, well past conventional marriage age. Women without the prospect of marriage should consider bringing a biological child into the world, I suggested, and the community should be supportive. Replenishing the population was one rationale. “Why be punished twice?” was another.

But I hesitated to put it into print. Unmarried pregnant women were stigmatized as wanton; artificial insemination was secretive. “Single mothers by choice” was not in the lexicon. The editors approved but friends cautioned, ‘Who needs this!’ Yet Arlene, single and nearing 40, urged me on. So I printed, anticipating criticism. Not only was there no flak, but affirmation followed in touching letters from liberal and Orthodox Jews; single women, parents and grandparents. I learned something lovely: For Jews, the ethic of raising children is so primary it supersedes other cherished conventions.

Only now, almost 40 years later, do I fully understand what I missed then. At a recent Kolech conference of Israeli religious feminists, four single mothers by choice spoke of the meaning of covenant to them in choosing to have a child. What I had once called primary family values was a deeper sense of the Jewish covenantal mission: the responsibility, the utter privilege, of transmitting generation to generation Jewish values, identity, narrative, tradition, faith and the task of repairing the world. That was what Hadassah readers had understood. —Blu Greenberg

Greenberg is a founder of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance.

Paris Souvenir

In addition to Hebrew columns, book reviews, author profiles and essays about Jewish holidays, i have written for Hadassah Magazine’s The Jewish Traveler. When I was assigned to write about Paris, the French Government Tourist Office went out of its way to accommodate me, pointing me toward the many places I could sample kosher French cuisine.

One elegant restaurant in the 16th Arrondissement stands out for another reason. No sooner had my wife and I been seated than the owner plunked himself down to lecture us on the fascinating history of the premises. “You see the green velvet mizrah?” he said. “That’s from a Jewish house of ill repute that used to occupy this building.” After much hondling, I bought the mizrah, and to this day it hangs on the Eastern wall of my home. —Joseph Lowin

Lowin’s book Art and Creativity in the Israeli Novel is forthcoming from Lexington Books.

Jewish and Proud

In 1972, my first drawing appeared on The New York Times op-ed page. That drawing on the Munich Olympics massacre was later exhibited in Paris at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs Palais du Louvre. When that same drawing was published on the cover of Hadassah Magazine (October 1972), an enduring relationship began. Over the years, my artwork has illustrated essays, the back page and even an entire issue on Jewish medicine. Elin Schoen Brockman’s 1999 interview “The Artist Will See You Now” prompted Congregation Agudas Achim in Austin, Texas, to commission me to design its Ark’s images and Torah mantles. My drawing Vashti was auctioned at a Jewish Museum of New York Purim Ball. I believe my art for Hadassah Magazine received such responses because of a readership dedicated to the pride of being Jewish and a nonwavering love and support of Israel. Incidentally, whenever one of my drawings was published in the magazine, my mother would kvell and tell all her friends. —Mark Podwal

Podwal is an artist and physician in New York.

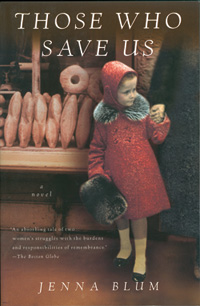

In 2005, Hadassah Magazine awarded my first novel, Those Who Save Us, the Harold U. Ribalow Prize. I still remember receiving the message and wondering if it were a prank call! One of the judges for the Ribalow Prize was Elie Wiesel, with whom I’d had the great honor of taking a course while getting a master’s at Boston University—and who I knew frowned upon Holocaust-themed fiction not written by survivors. That Wiesel was associated with a prize to my war-era novel bespoke once again his immense largesse, and the generosity of the Ribalow family and Hadassah Magazine gave this debut novelist encouragement for her future and a reconnection with her past.

Since 1999, when my Jewish dad passed away, I had drifted from the Jewish community; Hadassah Magazine reintroduced me to so many wonderful friends and readers. I will forever be grateful. —Jenna Blum

Blum’s novella, “The Lucky One,” has recently been published in the postwar anthology Grand Central (Penguin).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply