Arts

Exhibit

Design Providence: Jews and Midcentury Modern

“Mid-century Modern Designs—Shop This Look” reads a recent advertisement on The New York Times website. Glass-walled houses, teak furniture, the Eames lounge chair: In the middle of the 20th century it wasn’t called midcentury modern, just modern—until it became passé. And then, sometime in the 1980s, it was rediscovered.

Today, the style has become a fad approaching kitsch, with real estate listings featuring the term (if not the aesthetic) and shops and auction houses doing a brisk business in the furniture and artifacts. If the spare lines and bright, geometric patterns are everywhere, from the popular television show Mad Men to the home furnishings store Design Within Reach, what is often forgotten is how many Jews were among its star creators, including Saul Bass, Marcel Breuer, Richard Neutra and Saul Steinberg.

Their contributions are celebrated in San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum’s stunning show, “Designing Home: Jews and Midcentury Modernism,” the first to examine the subject, according to guest curator Donald Albrecht. Albrecht has gathered over 120 objects from 35 midcentury modern artists, from those who worked in architecture and interior design to ceramicists, weavers, photographers and graphic designers. The exhibit is at the CJM through October 6 and then will travel (contact the CJM for details: 415-655-7800; www.thecjm.org).

Museum-goers are greeted by a wall-size slide show featuring the work of many of the represented artists, among them Joseph Eichler, little-known outside California, who created subdivisions in both Northern and Southern California. His modest, well-designed houses feature wood paneling and open floor plans, blending indoors and outdoors. (Eichler refused to sign “restrictive” agreements, which discriminated against minority buyers, for the subdivisions he designed.)

A chart called “Network Connections” is also near the entrance. It shows the influence on the artists, both American-born and émigrés from Europe, of six seminal American institutions, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center.

The exhibit is divided into five sections. The first and main gallery features furniture, wall hangings and other artifacts. Textiles, ceramics and lamps line the walls and are interspersed with large pictures of period house interiors. Some of their creators are household names; others are only familiar through their work.

Among the latter is industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, born in New York in 1904. He is the creator of the iconic Princess telephone (a pink version is on display), Big Ben alarm clock, Honeywell thermostat and the squared-off white porcelain sink with chrome legs—some of which can still be found in homes across America.

At the other end of the spectrum is Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer, represented in the show not by his leather-and-chrome Wassily Chair, still produced today, but by an angular, no-nonsense wood-and-plywood desk and chair designed for a dormitory at Pennsylvania’s Bryn Mawr College. His work is also shown in photographs of a model home he created for MoMA’s garden in 1949.

Other imaginative furnishings include american-born George Nelson’s Marshmallow Sofa, created in 1956 and made of round red pads on a metal frame, as well as a lamp and an angular desk. (Nelson was design director of the Herman Miller furniture company.) Viennese native Rudolph M. Schindler, who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, is represented by a chunky wood-and-upholstery chair that incorporates a side table. Paul T. Frankl’s Skyscraper Bookcase has the staggered look of the rooflines of a row of high rises.

Decorating many of the modern houses were textiles and ceramics by Jewish artisans such as Anni Albers, who studied at Germany’s influential Bauhaus arts and crafts school (her matza holder incorporates metallic gold thread); and fellow textile artists Marli Ehrman; Lili Blumenau, who studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and later worked at New York’s Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum); Trude Guermonprez, who taught at Black Mountain and later at Pond Farm in California; and Ruth Adler Schnee, whose early studies with Swiss painter Paul Klee are evident in her witty, abstract designs.

Among the ceramicists in the exhibit are Bauhaus-trained Marguerite Wildenhain, who, after moving to the United States, taught at Pond Farm. American-born Ben Seibel’s stoneware dishes have a smooth-lined 1950s vibe. A luminous green glaze decorates a coffee set by Eugene Deutsch.

Gertrude and Otto Natzler, immigrants from Vienna, created earth-toned vessels in their adopted home of Los Angeles. The couple is known for their work in pottery forms and glazes; Otto invented more than 2,000 glazes. A number of their vases and a bowl are on display.

The smaller galleries focus on architecture, graphic arts (including advertising), Judaica and film. Richard Neutra’s Schiff Duplex, a three-story building in San Francisco with glass-and-metal-walls, is represented in photographs by Julius Shulman, one of the century’s most influential architectural photographers. Neutra, an immigrant from Vienna, designed the duplex for Dr. William and Ilse Schiff, affluent Jews who left Nazi Germany in 1935; the couple wanted a house that would showcase Bauhaus furniture from their pre-emigration Berlin apartment. Examples of the furniture, designed by acclaimed interior designer and architect Harry Rosenthal, including a cube-like desk and chair and a chrome-and-glass table lamp, are on public view for the first time. Also in the exhibit are Shulman’s photographs of a house that Neutra designed in Palm Springs, California, for Edgar Kaufmann Sr., founder of Kaufmann’s Department Store in Pittsburgh. (Kaufmann had previously commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece, Fallingwater.)

Single-family model houses embodying contemporary ideas were sponsored both by MoMA and Arts & Architecture magazine. Starting in 1945, the latter sponsored a series of inexpensive and efficient Case Study Houses in Los Angeles and Phoenix; MoMA commissioned Pittsburgh-born Gregory Ain to build a model house in its sculpture garden. Another such house was built by Marcel Breuer in 1949. (From 1950 to 1955, under the guidance of Edgar Kaufmann Jr., MoMA held a series of exhibits of household objects—teapots, lamps, broom handles—titled “What Is Good Design?”)

The small gallery showcasing modernist Judaica—another field in which, unsurprisingly, Jewish craftspeople shone—includes mezuzas, Seder plates and other ceremonial objects. Among them is a rounded copper alloy Hannuka lamp, an example of the work of Ludwig Yehuda Wolpert, for many years director of the Tobe Pascher Workshop for ceremonial Jewish objects at New York’s Jewish Museum. Wolpert’s polished brass mezuza is on exhibit, as is Victor S. Ries’s geometric brass mezuza.

However, it is in the field of graphic design that Jewish contributions were the most visible. Many logos—IBM, Kleenex, Fuller Paints, United Way, UPS—were designed by Jews, as were movie posters, book and magazine covers, record jackets and advertisements. Alex Steinweiss created jackets for Columbia Records from the 1940s, when the LP record was introduced, to the 1970s. His witty, colorful designs for albums from calypso to classical decorate one wall. George Tscherny’s magazine advertisements for Pan American Airways and Herman Miller furniture hang on another.

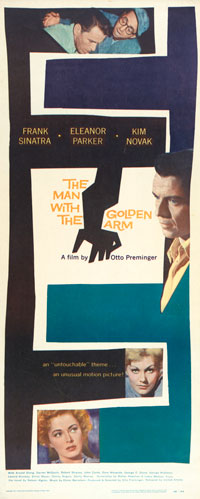

Prominent graphic artist Saul Bass created movie posters and famous title sequences for The Man with the Golden Arm, Exodus, Anatomy of a Murder as well as other films. A series of these sequences, including many for films by Alfred Hitchcock and Otto Preminger, are projected in a separate space.

“Designing home,” together with its excellent catalog, edited by Albrecht, explores ways in which the midcentury aesthetic derives from the Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, in 1919. The school championed unornamented, affordable and functional design. When Nazism forced the Bauhaus to close in 1933, many of its students and teachers immigrated to the United States.

As the Bauhaus pioneered modern architectural and industrial design in Europe, several American organizations took up the banner. MoMA, which opened in 1929, was the most influential. Not that Jews were always welcomed: For the museum’s 1938 exhibition, “Bauhaus: 1919-1928,” museum director Alfred H. Barr wanted to include a disclaimer that not all of the artists represented were Jewish. He was overruled. And, during the 1930s, Philip Johnson, founder of the museum’s department of architecture and design, espoused fascist causes and worked for the political campaign of anti-Semitic propagandist Father Charles E. Coughlin. (Johnson later apologized.)

Other institutions significant in promoting modern design were Black Mountain College, founded in 1933, which employed several former Bauhaus faculty members and championed that institution’s principles of hands-on learning and utilitarian design; the Institute of Design, founded in 1937 and now part of the Illinois Institute of Technology; Walker Art Center, which opened in 1927 with a focus on modern art; Arts & Architecture magazine; and the almost-forgotten artists’ colony, Pond Farm, founded around 1940 near Guerneville, north of San Francisco.

Jewish prominence in the modern design world is explored by Albrecht, curator of architecture and design at the Museum of the City of New York, and other authors and historians in the exhibit’s catalog.

Traditionally, Jews were often designers and creators of objects for the home, including ritual objects such as menoras and Kiddush cups, as well as their merchandisers. In early-20th-century Europe, Jews gained wider recognition with their participation in the Art Nouveau movement and in the Vienna Secession style with its simple, decorative patterns.

Meanwhile, in the New World, social workers tried to imbue tenement dwellers with the “gospel of simplicity,” explains Jenna Weissman Joselit in “Home Sweet Haym,” a catalog essay. The clean lines of Mission furniture were held out as models. Housewives, however, preferred overstuffed “matched parlor sets.” Nonetheless, a seed may have been planted.

The post-World War II period saw major strides in acceptance and progress for Jews. “For most postwar modern designers and their patrons, religion was a nonissue,” writes Albrecht. At the same time, Judaism gained admirers, in part because of the religious revival of the 1950s, when Jews were regarded as partners in the Judeo-Christian force against “godless communism” and in part because of the founding of Israel, which received widespread support in the United States.

The popularity of biblical novels and films, in which Jews were depicted as heroic, helped increase their acceptance, notes Michelle Mart in her catalog essay, “The ‘Christianization’ of Israel and Jews in 1950s America.” The opening of New York’s Jewish Museum in 1944 as well as the establishment of other Jewish museums throughout the country contributed to the recognition of Jews in world arts and culture.

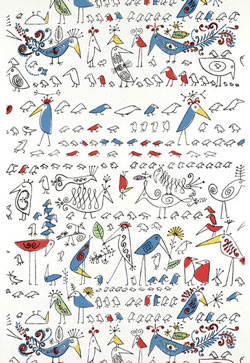

Among the best-known artists shown is Saul Steinberg. Born in Romania, Steinberg is most readily remembered for his 87 New Yorker covers and more than a thousand drawings for the magazine. The magazine also sponsored Steinberg’s immigration to the United States.

However, there are no Steinberg magazine covers in the exhibition; instead, on display is a large panel of wallpaper entitled Aviary, in which drawings of fanciful, bright-colored birds march from right to left and back. It is an example not only of midcentury modern design but of timeless imagination.

I would hang it on my wall in a heartbeat.

Renata Polt is editor and translator of A Thousand Kisses: A Grandmother’s Holocaust Letters (University of Alabama Press). She lives in Berkeley, California.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply