Issue Archive

Israeli Life: Pop Music and the Bible

Today’s leading Israeli singers are ‘God obsessed’; they mine traditional stories and customs—from Shabbat to the Golden Calf—to create spiritually inclined rock ’n’ roll.

“Let us leave Egypt,/ Come to the desert,/ Perhaps we’ll find water there,” croons dark-haired, wide-eyed 36-year-old Etti Ankri. “We built pyramids, interpreted dreams./ But nothing was ours,/ Only salt and tears./ And sometimes I just want to give up,/ Pharaoh’s [within] me, and I feel the pain of Egypt….”

The Israeli singer is finishing the final song of her concert, part of a conference on Jewish identity sponsored by the magazine Eretz Aheret. Her song, “Yetziat Mitzrayyim” (“Exodus from Egypt”), ostensibly describes the Israelites leaving Egypt, but she has transformed it into a personal midrash.

“The Pharaoh might be within me,” she says. “I might be enslaved within an old idea and weary of seeking, but I must keep on praying for the waters to open, the waters of life.”

Ankri sees her music as a tool for searching, part of a lifelong dialogue with God and Jewish sources.

The popularity of “Yetziat Mitzrayyim” and other songs that fuse texts from the Bible or liturgy with a variety of ethnic sounds and genres is one aspect of a general Israeli search for identity and spirituality, a Jewish renewal movement that has contributed to increased interest in Jewish texts and liturgy.

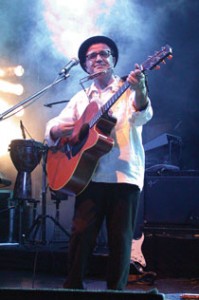

The most culturally exciting development in israel in recent years is the emergence of a spiritual… popular music,” said Yossi Klein Halevi, a senior fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem, in an interview on Blogs of Zion (www.blogsofzion.com). “The best bands and singers, Shotei Hanevua, Ehud Banai, Etti Ankri, Beit Habubot, Mosh Ben Ari, are God obsessed.

“And what’s wonderful about Israel’s God Rock is that it is not fundamentalist, but the opposite. It is pluralistic, it is universalistic and it embraces other religions. [W]hat it says to me is that the old model of secular versus Orthodox is breaking down among younger Israelis.”

Introspective 45-year-old Banai has long combined rock and pop with Eastern strains and biblical sources. He uses the text to create modern moral parables. For example, his song “The Golden Calf” refers to the idolatrous worship by the Israelites, but it is also about the confusion of a hapless, leaderless society: “There’s no leadership./ The people are lost./ There’s no one to hit the rock./ In the darkness, everyone’s fighting over every crumb,/ Around the golden cow.”

Banai comes from an entertainment family: His late father was an actor and storyteller; his uncle, Yossi Banai, is a renowned actor and singer. He grew up hearing music in his home in the Mahane Yehuda area of Jerusalem.

“It took me a long time to find myself,” he explains. “But once my grandmother—who was herself a wise and funny storyteller—heard me strumming on the guitar. It reminded her of my grandfather’s haunting melodies, and she encouraged me.”

Incorporating moral parables and the Bible into music is not a uniquely Israeli phenomenon, notes Aviva Dayan, a flautist and songwriter who studied musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Joan Baez has drawn upon classical English ballads such as ‘Barbra Allen,’” she says, “and has even used biblical stories…in a midrashic manner.” Banai and other Israeli singers, influenced by Bob Dylan and Baez, naturally turned to the Tanakh for their parables.

The Beatles also made a big impression on Banai. “I was influenced by the sense of space [in their music], of moving around,” he relates, “and I traveled to Safed and Acre, but the poet Oded Peled said to me, ‘In a big country, it’s geography [and] space that counts. What we have in this small land of Israel is breadth, an extension in time.’ I understood that I must make my journey on the long road back to the past.”

“Banai makes biblical figures sound contemporary,” says Menahem Granit, director of Channel Gimmel at Kol Israel Radio. The singer is adept at relating the past to the present. In “David and Saul,” Banai describes an interaction between the two legendary figures: “Late at night/ Everyone has gone to bed./ Only Saul is up depressed./ Picks up the telephone to David./ Maybe you will jump over ya, David./ My soul is heavy and dark,/ Bring your guitar,/ because there is light in your fingers.”

Like Banai, Ankri was also exposed to music from a young age. She grew up in Lod, part of a Tunisian family. “My grandmother and mother sang all the time,” she reminisces. “I heard Tunisian, Indian, Arab music. My father loved Flamenco music.” It is only in the last 12 years that Ankri has become increasingly concerned with spiritual issues. “It’s not that I suddenly woke up to Judaism,” she says. “It’s always been there, but sometimes…you lose contact and then reconnect.

“[Today] my whole life is connected with Torah,” explains Ankri, who observes Shabbat and describes herself as spiritual. “I study in havruta and try to find my own way within Torah. I translate psalms into my own songs. My last album, Hameitav, were songs of praise, all touching on my dialogue with God. The critics were very positive. If they had heard it from a Hasid, they would think it’s crazy.”

Young Israelis today enjoy exploring different kinds of world music, explains bass player Avraham Sasson Eliyahu, but that brings them back to their own roots. “They travel in India and are attracted to Indian spiritual music,” he says, “but then they seek something closer to themselves. They try to find a place where they feel comfortable and begin to look at Jewish sources of spirituality and music.”

“The recent trend is to reach out to exotic music from Africa and Asia,” says Granit.

Idan Raichel’s music relies on the convergence of African sounds and pop. One of the most popular young singers today, Raichel draws upon the music Jews brought with them from Ethiopia, which is rich in Jewish sources; he only has to go five minutes to the Ethiopian community near his home in Tel Aviv for African sounds that are tied to the Tanakh.

The dreadlocked, 29-year-old Raichel sings mesmerizing melodies with instrumentalists of Ethiopian, Iraqi and Caribbean ancestry in his band, The Idan Raichel Project.

His music is often sung both in Hebrew and Amharic, an expression of the pride he feels in the blending of culture in Israel today. Raichel subtly weaves biblical phrases and expressions that echo in the collective unconscious into his lyrics. One example, “Mimaamakim Karati Elayikh, Bo’i Elai,” (“Out of The Depths I Called to You, Come to Me”), is a recent hit. Initially, it sounds like a straightforward rendition of Psalm 130, where the psalmist calls to God from the depths of his soul. But Raichel transforms it into a love song, calling out to his lover.

Another romantic song, “Hinkha Yafeh” (“Here You Are, My Beautiful Lover”), echoes Song of Songs: “I searched the teeming, lying streets of the city,/ And I didn’t find her./ I found the guards that surround the city./ But my lover was not to be found….”

Love songs are a common motif in popular music. “It is no wonder,” says Edwin Seroussi of the Hebrew University Department of Musicology, “that Song of Songs, the love poem par excellence in Jewish sources, is used in much popular music.”

In fact, the Bible has always provided Jewish music with its themes and librettos. “For hundreds, even thousands of years, piyyutim, the song lyrics of Eastern Jews such as Rabbi Shalem Shabazi, [Israel ben Moses] Najara and [Solomon ben Judah] Ibn Gabirol drew heavily from biblical sources as a means of religious expression,” says Dayan. “These songs are sung at the Shabbat table to this day. With the Zionist return to the land of Israel, the pioneers from Eastern Europe and Russia sang songs around the campfire, incorporating biblical themes in order to reinforce the connection of the pioneers to the land of the Bible.”

“The Tanakh was Israel’s history book, its point of reference,” explains Seroussi. “The ideological climate in [David] Ben-Gurion’s time put emphasis on the Bible and promoted music based on it, as part of the Zionist ethos. Many songs about the return to Zion sound like they are taken straight from the Prophets.”

Granit points out that the Army made these songs popular. Many of Israel’s most important singers, such as Arik Einstein, Shlomo Artzi and Matti Caspi, came out of the Army.

While they raised the morale of the country, “wars gave rise to songs based on biblical sources,” he says. “After the ’56 war, the Army troops sang ‘Mul Har Sinai’ [‘In Front of Mount Sinai’]. The Six-Day War brought an outpouring of songs like ‘On the Road to Bethlehem.’

“But,” adds Granit, “these patriotic allusions did not catch on after the Yom Kippur War or Lebanon war.” Interest in a more international sound came with the introduction of the Beatles and Bob Dylan. Granit himself was infected with the sounds of rock ’n’ roll. “I saw John Lennon as a soulmate,” he explains. “Music became international, and Israeli music also opened up to the world. Today, Israeli music is very much integrated into world music.”

“Israeli singers may have been influenced by non-Israeli artists such as Baez,” Dayan adds, “but they also have drawn from the ballad tradition in Spanish and Ladino cultures.

“The multicultural heritage of young Israelis means that they have inherited these traditions from various Jewish and non-Jewish sources.”

The renewal of interest among many secular Jews in songs with biblical or Judaic imagery, mixed with those international sounds, is a recent phenomenon.

“In the 70’s and early 80’s, Israelis negated religion,” says Shira Ben Sasson, coordinator of religious pluralism at Shatil, the New Israel Fund’s Empowerment and Training Center for Social Change Organizations in Israel. “They fought for civil rights, freedom from religious legislation, what they saw as religious coercion. But since the end of the 80’s, secular Israel has reappropriated the Jewish bookshelf. Tanakh, Talmud, Kabbala help the individual discover his personal identity.”

Indeed, in the last decade a dazzling proliferation of programs have been developed to instruct secular Israelis about Judaic sources—educational frameworks that teach Talmud, Midrash, liturgy and Kabbala as well as Bible to the nonobservant. Among these programs are a new secular hesder (joint Army and Judaic studies program) in Tel Aviv under the aegis of Bina, the United Kibbutz Movement’s Center for Jewish Identity and Hebrew Culture, and Bamidbar Beit Midrash, the Center for Jewish Learning in Yeroham and Sde Boker in the Negev, which is teaching Jewish studies in factories and jails.

The secular Israeli studies Jewish texts in order to integrate into his world the voices bursting forth from the depths of the tradition, in order to decide in an autonomous way how to structure his world,” says Micah Goodman, one of the founders of Midrasha Hagavoah L’Manhigut, a school for leadership training in Kfar Adumim.

In this atmosphere, singers also feel free to express explicitly religious sentiments, from expressions of gratitude to God to an outright yearning for the time of the Messiah and the restoration of the Temple. Raichel’s “B’Yom Shabbat,” which uses the poetry of 17th-century Yemenite poet Shalem Shabazi, is one example: “On the day of Shabbat, I will praise God,/ My redeemer lives./ And I will bring sacrifices of incense,/ On the day the Temple is restored.”

“Zionism has taken different forms,” Dayan says, “but its involvement with the Tanakh is still part of Israeli consciousness and a way of reclaiming Judaism for secular Israelis.”

“Young people have so many diversions,” adds Granit. “Everything is celebrity, glamour and pyrotechnics…. But in Israel there is still the gathering of the tribe around the bonfire. There’s still intimacy, a sense of a shared experience [and destiny]. The singers are more down-to-earth. You can touch them.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Wilbrand Rakhorst says

I collected bible in secular popmusic. You can look into the database Godisadj.nu(muziekbijbel.nl) the other half In have in my google drive. in total IT,s thousand OR more. Greetings from the netherlands. thank you for the very interesting article. I learned some hebrew when In studies theology. Unfortunately

not enough to understanding modern hebrew songs.