Issue Archive

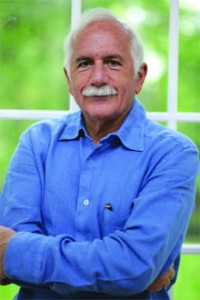

Interview: Moshe Safdie

Moshe Safdie’s architectural legacy runs from his first revolutionary work, Habitat, in Montreal in 1967—which reconfigured the typical apartment complex by incorporating open architectural features of single-family houses—up to his recent redesign of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem. Today, at 67, this Israeli is profoundly influencing future generations as director of urban design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Safdie’s vision is embodied in museums, national theaters, universities, airports and entire cities.

Moshe Safdie’s architectural legacy runs from his first revolutionary work, Habitat, in Montreal in 1967—which reconfigured the typical apartment complex by incorporating open architectural features of single-family houses—up to his recent redesign of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem. Today, at 67, this Israeli is profoundly influencing future generations as director of urban design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Safdie’s vision is embodied in museums, national theaters, universities, airports and entire cities.

Q. Your firm is based in Somerville, Massachusetts. But your fingerprints are everywhere in Israel, in old cities and new, in memorials and in the nation’s gateway airport. How does working in Israel compare with other countries?

A. I can’t imagine anywhere else on the globe where it would have been possible to conceive and realize a totally new city on the scale of Modi’in. I won the Ben-Gurion Airport project even though I had never before done an airport. Other countries would have asked, “How many airports have you done?” before putting me on the short list of candidates. The opportunity to help rebuild the center of Jerusalem, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City and the Mamilla district were equally unique. On the other hand, the number of projects I have planned that did not come to fruition is also mind-boggling. The Western Wall plan to reestablish the area’s historic topography has not been realized because of religious objections. A plan for the Desert Research Institute at Sde Boker, also not. Israel is a tough case…in the sense that there are so many skeptics. You have to work harder to realize your visions.

Q. What will make a 21st-century city a great city?

A. In the past, it was a precondition for a city to be worthy to have a heritage, a history. Whether it was Barcelona or Florence or even New York or Boston, there is a rich heritage. Today we must recognize that some world cities have had their heritages erased intentionally to [remove] their colonial past: Singapore, Shanghai and Beijing, much of Warsaw. We will emerge with 21st-century cities that are significant but have much less heritage. When we think about great cities, we think naturally about cultural life, about creating a force and also about physical features and beauty. Tel Aviv is a very vital city culturally, with a nice shoreline [and a] natural setting that is quite wonderful, but it gets no high marks as a city of great architectural beauty. Jerusalem, on the other hand—very beautiful, but very neglected with a struggling cultural life. Which cities have it all today? Milan has it, Barcelona, too.

Q. What personal inclinations do you bring to a new task?

A. I am probably a minority in my profession, but I must be inspired and curious about the place in which my work is. My antennae go up to understand the place. Boston is not Philadelphia, not to mention the differences between Jerusalem, Toronto [and] Singapore. Place is unique in both the micro and the macro. Tel Aviv is different from Jerusalem, and within Jerusalem, Mamilla is different than Yad Vashem. I must gain a profound understanding of the venue and allow this to become a shaper of the design. I don’t believe I have one signature style… but rather an integration of my perceptions with the distinct local attributes. [This] makes me feel like I am reinvented all the time and rediscovered every time I create something new.

Q. How did you decide what is ‘right’ for the new terminal at Ben-Gurion Airport?

A. Ben-Gurion…is a gateway for a small country that aspires to turn arrivals and departures into something of a ritual. The initial master plan channeled arriving passengers down into a maze of corridors and tunnels into passport control. It took departing passengers through upper levels, the king’s highway, to the plane. The first thing I realized was the need to elevate the arrival experience. Ninety-five percent of the arriving passengers are coming into an experience—new olim, religious pilgrims and so on. You cannot shunt them down a corridor to a basement. Let them be on the upper level, seeing the country as they get off the plane. I created this mutual moving up and down ramp where people entering and leaving the country are conscious of the others’ movement and can even wave to one another. This all had to do with understanding…that this airport serves a core gateway function. Most airports are constructed with steel; I chose precast concrete, which is more suitable to the Israeli construction industry and also more economical.

Q. What kind of special connection and challenge has Yad Vashem presented for you?

A. My relationship with Yad Vashem is very long term. It began with the Children’s Memorial in the 1970’s. For a decade my plan sat on a shelf. Only later did a benefactor come whose son had died at Auschwitz. He saw the model for the children [it is hollowed out from an underground cavern, where memorial candles are reflected infinitely in a dark and somber space] and eventually built it. There is a complexity…at Yad Vashem that is not matched anywhere else. Every single thing is symbolically charged. Next, I did the transport memorial [depicting a railway car barely balanced on a destroyed bridge].

When they decided to redo the entire place, they had a competition. There were many different concepts. It has been a long journey, not a simple one. Even the project that just opened was a 10-year process for me. It involved more meetings per square meter than any other project I have done. [It] is probably the most profound and perhaps most important piece of architecture I have ever done… All the letters and comments I get have made this a very moving experience. I put my heart and soul into it, and you can only do that with genuine humility—otherwise, it just falls flat on its face. For me, that means never verbalizing what you meant symbolically. You must let people be themselves and associate their own symbols with what you have created.

Q. In what way did you make the Rabin ethos transcend the mere blueprints of The Yitzhak Rabin Center for Israeli Studies in Tel Aviv?

A. Owing to my personal relationship with Yitzhak and Leah Rabin, and now with their daughter, Dahlia, this is a very emotional work for me. I had spent much memorable time with the Rabins before [Yitzhak’s] assassination, which was a monumental national tragedy. When Leah said she wanted to build the center as a museum of his life and times, as an archive, I was entrusted with an opportunity to create an expression of my intense admiration for Rabin, who was transformed from a warrior to a peacemaker. I tried to find a way…to demonstrate this paradigm shift…. It has been a labor of love for me.

The exposed electrical power station known as “Redding 3″—which forms the base of the building—is somewhat symbolic of defense, with its mass representing Rabin the warrior. The installation was a top-secret facility in the 1950’s to generate power during wartime. The structure above [the Rabin Center itself] is all about lightness and whiteness and represents the latter phase in Rabin’s life as the statesman seeking peace. I am not fond of spelling out all my symbolic intentions in buildings as some architects love to do, but rather let people read into it what they need and want.

Q.Which work are you proudest of?

A. I must at least think of Habitat, my best-known building. I did it as a kid; it was a work of wonderment. Yad Vashem is at the other end of the spectrum. There, architecture was tested from adaptation through memorialization. Of course, you realize it’s like talking about children. How can you say which is your favorite kid? I have only four children, but no way can I say which is my favorite. They are all…absolutely unique.

Q. As a citizen of the world, which flag has the most meaning for you?

A. I am an Israeli. I was born a Jew in Israel at an extraordinary time. I was privileged to be here when the very state was born. Then, I found myself in Canada, a nation that has been very good to me on many levels. And for the past 25 years, I have been based in, actively working in the U.S. I have three passports. I am comfortable with it. I really do feel like a citizen of the world.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply