Issue Archive

The Arts: Max Liebermann: A Belated Impression

From the 1880’s to the 1930’s the premier artist in Berlin was a Jew whose work was later reviled by the Nazis. A new exhibit showcases his talent for an American audience.

At the age of 26, after a decade of academic studies and apprenticeship, the German Jewish painter Max Liebermann signaled his coming of age as a young artist with Self-Portrait with Kitchen Still Life. The large oil on canvas, his first self-portrait, measures almost three foot by five foot and shows a smiling cook, the artist, standing in front of a table laden with food. Amid the profusion, a keen-eyed viewer can detecta kosher seal on the chicken—an homage to his parents’ observant lifestyle.

Though Liebermann had not yet gone on the Wanderjahre, a period of travel and exploration customarily taken by German artists after their formal training, the piece contains evidence of his lifelong approach to his work: adaptation and reinterpretation, taking the subjects and formalistic techniques of earlier artists and then infusing them with his own vision and message.

In the case of Kitchen Still Life, he used 17th-century Dutch paintings that combine portrait and food, often given as wedding gifts. In Liebermann’s version, the theme has a playfulness and a personal touch, from the smiling cook to the kashrut symbol to the profusion of foodstuffs, thought to be an allusion to his mother’s culinary skills.

Kitchen still life is one of 70 paintings and drawings assembled by senior curator Barbara Gilbert at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles for the exhibit “Max Liebermann: From Realism to Impressionism.” On view through January 29, 2006, the exhibit represents the first American survey of the artist’s work. The Jewish Museum of New York will host a smaller version, with 40 to 45 paintings, from March 10 to July 9, 2006.

Considered the greatest artist in Berlin for most of his lifetime, Liebermann was born in 1847 and died at the age of 87. His life spanned a time that saw incredible freedom and success for the German Jewish community and ended with the start of the Nazi era. He created some 1,500 paintings, studies and drawings, about one-third of which disappeared during the Nazi regime and World War II.

The Skirball’s Getty Gallery welcomes visitors with an introductory eight-minute video on the artist’s life. The gallery itself is divided into 10 sections, encompassing both Liebermann’s development as an artist, from the realism of his youth to the loose impressionism with which he created the masterworks of his later years, and his personal reactions to the tenor of his times—his patriotism during World War I, his romanticization of rural life and, finally, his increased isolation from Berlin’s art world and German society toward the end of his life.

Three self-portraits adorn the first section, including Kitchen Still Life, whose smiling “cook” differs sharply from the stern visage in Self-Portrait with Brush and Palette, which he created at age 66, and 20 years later, Self-Portrait with Brushes and Palette.

Five early realistic paintings of workers, peasants and market scenes in the second section bear clear marks of the influence of Frans Hals and his Dutch contemporaries. Typical is the Vegetable Vendor–Market Scene; its ruddy palette and strong contrasts between dark and light center on two women in peasant attire. One, arms akimbo, is trying to sell cabbages and other wares to the second woman.

At the Swimming Hole shows 10 boys gathered on a dock. Each of them, in various stages of undress, is given an equal amount of space and is preoccupied with himself.

“This pairing of solitude and sociability,” says Mason Klein, associate curator of The Jewish Museum, “is especially evident in many of Liebermann’s paintings of rural peasantry and in later portraits of the residents of orphanages and old-age homes.”

Liebermann rarely used Jewish themes in his paintings, perhaps discouraged by the reception of his 1879 work The Twelve-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple with the Scholars, which shows a young Jesus debating a group of rabbis. To find models for the rabbis, Liebermann visited synagogues in Amsterdam and Venice. Jesus was originally portrayed as a scruffy, unkempt boy with gesticulating hands and a distinctively Semitic nose. The painting elicited howls of outrage in the Bavarian parliament that a painter, and a Jew at that, would depict Christ in such an unflattering manner.

As a result of the attacks, Liebermann changed the painting to show the young Jesus in a clean white robe with an “Aryanized” nose.

Because of security restrictions imposed by the lending museums in Berlin and Hamburg, the Skirball will display only the original crayon-over-graphite drawing of the “Semitic” Jesus in section three, while The Jewish Museum will exhibit only the “Aryanized” final painting.

“[Leibermann] was bewildered by the fierce response to the [unkempt Jesus] and unwilling to understand the attacks as anti-Semitic, illustrating his refusal to acknowledge a cultural divide between Gentile and Jew,” writes Klein in the richly illustrated 220-page catalog that accompanies the exhibit.

Liebermann commented about the furor that “I never would have dreamed of such a thing when I painted that innocent picture and the clerics demanded that it be removed to the side

by the opening of the exhibition. I was consoled by the approval of my colleagues, and people congratulated me on the picture, [saying]…it is the best that has been painted in Munich in 15 years.”

From then on Liebermann avoided New Testament depictions, turning to the Old Testament for Samson and Delilah, which he did not finish until 1910. The final painting, also placed in the third section, shows a naked Delilah shearing Samson’s sideburns while Philistine soldiers lurk in the background.

The Netherlands was another great influence on Liebermann’s work. From around the 1870’s until the outbreak of World War I, he made annual trips for both work and rest. While there he created realistic works depicting craftsmen and peasants, paintings that earned him praise for his skillful technique, but ridiculed for the subject matter. In particular, his Women Plucking Geese (not in the exhibit) earned him critical jeers and the moniker “the apostle of the ugly.” The artist’s tribute to the laboring class unites the works in section four, from Brabant Lacemaker–Study with Three Figures (second version) to Girl Sewing with Cat–Dutch Interior.

Liebermann manifested a lifelong interest in social institutions, represented here by Study for Recess in the Amsterdam Orphanage, View of the Inner Courtyard and Study for Old Men’s Home in Amsterdam.

Liebermann’s return to Berlin in 1884 marked a distinct change in his personal and artistic life. He married the former Martha Marckwald, and the following year their only child, Kaethe, was born. He started collecting French impressionist paintings by Manet, Degas, Renoir and Pissaro, whose influence led to a number of changes in his own perceptions. He eventually amassed a large collection.

His new style revealed a reduction of objects, light and movement to the simplest forms, executed with concise but abstract brushstrokes. He also started to work in the medium of pastel, which allows greater spontaneity than oil paint.

As he developed a looser and more spontaneous impressionist style, Liebermann was hailed by art writer Julius Elias as “the founder of German naturalism, who at the time made French impressionism German.”

In the next groupings, prime examples of this impressionism include: Beer Garden in Brannenburg, which demonstrated his growing ability to merge human form with the natural environment; and The Artist’s Wife at the Beach, a striking portrait of his wife. His somber Winter and Country House in Hilversum clearly show Manet’s influence, as does the playful Tennis Game by the Sea, with ladies in full-length skirts and hats.

In 1898, Liebermann entered the politics of culture when he joined 65 antiestablishment rebels to create the Berlin Secession, which staged exhibitions of modernist art rejected by most leading museums and galleries. He was elected the movement’s first president, a role he held until 1911. This put Liebermann in a leadership position among the German avant garde, and he quickly proved his international outlook by displaying German and French paintings side by side in secession exhibits.

During this period, despite his new duties, Liebermann entered into the most adventurous, experimental and exuberant phase of his career; his series of paintings of the parrot keeper at the Amsterdam zoo, including Study for the Parrotman, is considered the outstanding example.

Section six of the exhibit has an early and somewhat sketchy and abstract Study for the Parrotman and Ropewalk in Edam as well as two distinct impressionistic versions of Jewish Quarter in Amsterdam, complemented by Vegetable Market in Amsterdam.

Liebermann’s beloved beach scenes are shown in the same section with, among others, Promenade at the Dunes at Noordwijk; Horseback Rider on the Beach, Facing Left; and Horserace at Cascina. With the outbreak of World War I, Liebermann joined in his countrymen’s patriotic fervor, even suggesting in a letter that “war seems to be necessary to curb the excessive materialism of peacetime.” He contributed a number of lithographs to the Kriegszeit Künstblätter, or Wartime Art Newspaper, of which four are displayed.

In The Kaiser, a saber-wielding Wilhelm II on horseback leads a charge; in March, March, Hurrah, enthusiastic German soldiers go on the attack; and in The Samaritan, a medic tends to the wounded.

Most interesting is a sketch, inscribed To My Beloved Jews, of Russian Cossacks killing Jews during the 1903 Kishinev Pogrom. In 1916, however, two years into the war, Liebermann returned to more peaceful outdoor scenes such as Evening at the Brandenburg Gate and a new Beach Scene in Noordwijk.

With the end of the war, Liebermann again explored new avenues. He became a highly regarded and well-paid portrait artist whose sitters included Albert Einstein, Richard Strauss and German President Paul von Hindenburg.

Compared to his rather stiff late-19th-century family portraits, Liebermann now demonstrated an increasing ability to capture the personality of his subject. Over half his commissions in the 1920’s came from Berlin’s upper-middle-class Jews, including portraits of community leader Heinrich Stahl and publisher Bruno Cassir, painter Lovis Corinth and the eminent surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch—all placed in section eight of the exhibit. Among the rare portraits of women is that of Adele Wolde and Bertha Bierman; the latter is considered one of his best.

As the Weimar Republic brought a brief interlude of liberalism to Germany, Liebermann reached the apogee of his cultural-political influence. In 1920, he was elected president of the Prussian Academy of Arts, a prestigious post never held by a Jew before. Liebermann was repeatedly reelected, but resigned in 1932 after a 12-year tenure, in the face of rising anti-Semitism.

With advancing age, liebermann retreated increasingly to his spacious villa in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, which ironically later became known as the setting for the Nazi gathering that outlined the Final Solution. During the last nine years of his life, from 1926 to 1935, he concentrated on intimate family scenes and views of flowers and gardens, such as The Artist Sketching in the Circle of His Family, showcased in the last two sections.

Liebermann used compact, dense colors in his garden paintings and perfected the blending of human figures with nature, particularly in the Cabbage Field. Other Wannsee paintings include The Artist’s Garden in Wannsee: Birch Trees by the Lake and The Flower Terrace in the Wannsee Garden, Facing Northwest.

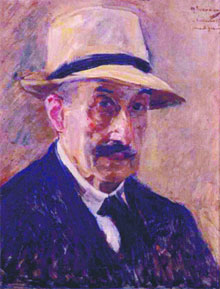

The final section shows a portrait of a still dapper artist in 1929 in Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat. In contrast is his 1934 Self-Portrait in Smock, with Hat, Brush, and Palette, which shows a much older, grayer man, wearied perhaps by the politics and rising tensions of the time.

The last entry in the exhibit is the lithograph To The Mothers of the Twelve Thousand, finished shortly before his death. It refers to the 12,000 Jews who died fighting for Germany in World War I. The work, showing a woman standing by the grave of her son, was sponsored by a Jewish veterans’ organization. The group, and perhaps Liebermann too, hoped that the publicity might protect former Jewish combat soldiers against new anti-Semitic laws.

With Hitler’s ascent to power, Liebermann became a favorite target of the Nazi press as a modern painter, political moderate and most visible representative of the Berlin Jewish community. His paintings were removed from museums and flaunted as examples of “degenerate art.”

Liebermann became increasingly depressed. In a famous anecdote, he met an old acquaintance who observed that the artist did not look well and inquired whether he was eating enough. Pointing to the swastikas festooning Unter den Linden boulevard, Liebermann replied, “I can’t eat because I want to throw up.”

Liebermann died in Berlin in 1935, and the passing of the man who had been a German cultural icon for so many decades was completely ignored by the Nazi-controlled press. His wife, Martha, who refused to leave the city where her husband was buried, committed suicide in 1943 when she was 86, after receiving her deportation orders to Theresienstadt.

During his life Liebermann hardly fit the image of the bohemian artist. He was a devoted family man and, even when painting at a beach, always wore a suit, tie and hat. In addition, he was a prolific and conscientious correspondent, writing thousands of letters. In one, he characterized himself as “an inveterate Jew, who otherwise feels like a German.” Most of his life he was able to combine and balance the two loyalties. As late as 1931, he wrote to Tel Aviv Mayor Meir Dizengoff, “Art knows neither political nor religious boundaries…although I have felt as a German throughout my whole life, my kinship to the Jewish people is no less alive in me.”

But only three years later, responding to an appeal for support of a Zionist youth group, Liebermann observed: “We have only awakened now from the beautiful dream of assimilation and…I am too old to emigrate, but for the Jewish youth there is no salvation but to leave for Palestine, where they can live as a free people.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply