Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: More Alive Than Ever

Counterintuitive, maybe, but the digital age has made the past more accessible than ever: Last year, in a collaboration between Google and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the oldest-known fragments of the Hebrew Bible, part of the Dead Sea Scrolls, went digital. Within four days, the site, https://dss.collections.imj.org.il, had a million hits.

George Blumenthal, founder of the Center for Online Judaic Studies and funder of the initiative, explained the phenomenon simply: “The Dead Sea Scrolls are magic,” he said.

And it seems they are just as powerful in the flesh. Earlier this year, visitors thronged to see “Dead Sea Scrolls: Life and Faith in Biblical Times” at Discovery Times Square in New York to get a glimpse of the scrolls offscreen. The exhibit has moved south to Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute (215-448-1200; www.fi.edu), where it will be on view in The Mandell Center through October 14.

On display with the scrolls is an astounding collection of artifacts ranging from the Iron Age to the era of the Second Temple and beyond—the most comprehensive exhibition of the scrolls ever shown in the United States. But the exhibition, created by the Israel Antiquities Authority with the help of Discovery Times Square and the Franklin Institute, is more than just a catch-all for the period leading up to the writing of the scrolls. It paints a deliberately eclectic picture of life in the Holy Land, one that spans thousands of years and the myriad practices of the religion that ultimately culminated in Judaism as we know it today.

A multimedia presentation kicks off the journey into the past. Visitors are ushered into a dark room and surrounded by high-definition images of the Dead Sea and its environs, then the sights and sounds of a bustling, Second Temple-era Jerusalem. The stage set, the traipse into the past continues down a long corridor—a walkable timeline stretching backward from 1948 and mapping every period of rule over the Holy Land from the British Mandate to the biblical era. Traveling backward, there already exists a tension between the timelessness of the text—what made the land important to so many different people—and constant cultural, religious and political shifts.

The core of the exhibit delves into the period around 1200 B.C.E., when the early Israelites lived and worshiped in biblical Israel, and encompasses the momentous and the mundane: A reconstructed four-room house, complete with dishes and cookware, affords a glimpse into Iron Age domesticity; just a few steps away lie earthenware vessels bearing the inscription of the king, probably used for the collection of royal taxes during King Hezekiah’s reign.

Iron arrowheads and flint stones bring the action of the Bible to life, documenting the battle at Lahish in 701 B.C.E. during the Assyrian conquest of Judah. From a fragment of a schoolboy’s alphabet table to letters written by the commander of the Judean fortress at Arad during the 7th century B.C.E., we see the written word flourishing at every level of society—a testament, along with other archaeological evidence, to the Golden Age documented in the Bible.

Indeed, part of the fun is tracing the biblical narrative along with the archaeological one, seeing where they intertwine and diverge. The curators have taken care to show that the Bible represents an idealized portrait of faith during its time, a time when Judaism—even the Bible itself—was taking shape. But, pointed out Lawrence H. Schiffman, an expert on the scrolls and academic adviser to the exhibit, this should come as no surprise to those who have read the Bible thoroughly.

“The Bible says people were doing other stuff,” he said. The text makes it clear that the strict version of monotheism it describes “wasn’t the only way of practicing,” as the artifacts with the greatest shock value attest to. Included in the exhibit are figurines thought to represent the Canaanite goddess Asherah. According to researchers, many Israelites believed her to be their God’s consort; a number of these female figures have cropped up in excavations of ancient houses. So have small incense altars—an example is also on display—evidence that biblical bans on burning ritual incense outside the Temple were flaunted in private households.

These pieces tell the story of localized folk religion influenced by other cultures, giving way to a faith governed by a central authority first embodied by the Temple in Jerusalem and, later, by the text of the Bible.

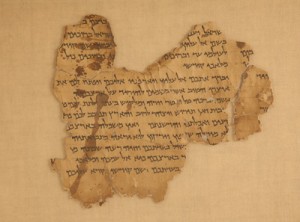

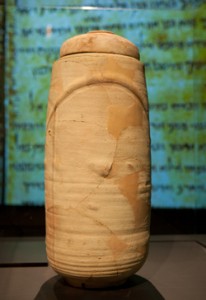

And that is where the scrolls come in. First discovered by Bedouin shepherds in 1947 in Khirbat Qumran, next to the Dead Sea, the scrolls constitute a wide body of ancient literature written in Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic. Subsequent excavations uncovered thousands of parchment fragments spanning the years from 250 B.C.E. to 70 C.E. The story of their discovery and introduction to the world just as Israel was on the brink of statehood, presented in a video in the exhibit, is fascinating.

Twenty scrolls are part of the exhibit and four of them are making their public premier with this exhibit. To preserve the delicate parchment, only 10 are shown at one time, visible through dimly lit protective glass in a round case at the center of a large atrium, the exhibit’s culmination.

There are copies of Isaiah, Deuteronomy and Psalms—the most ubiquitous of the biblical scrolls found at Qumran. Approximately 1,000 years older than the oldest copies of the Bible known before 1947, these scrolls connect the Bible to antiquity—to a time when different versions existed and the text was still taking shape. Variations among the copies of Deuteronomy and Psalms that diverge from the standard text tell us as much.

Some scrolls, for example, give us insight into the individuals who penned them. Various pesharim—early biblical commentaries—reflect the authors’ belief that the Bible contained hidden messages that only they were privy to. Pesharim also refer to contemporary events: The pesher for the book of Nahum replaces the people of Nineveh, the original setting of Nahum’s prophecy, with a designation thought to refer to the Pharisees, who the inhabitants of Qumran saw as false practitioners of their faith.

Messianism and references to the end of times, both themes that proliferated among different groups during the period, are also rampant among the texts. The Community Rule Scroll details the seasons and festivals of the year as well as the guiding principles and philosophies of the Qumran community.

Vessels used for ritual purity—a topic of controversy at the time—leather phylacteries and coins that may have been collected for a community tax are among the pieces displayed alongside the scrolls, bringing the ancient community to life.

The Qumran community began to take shape between 166 B.C.E. and 63 C.E., during the period of the Second Temple, when the Jews had thrown off the yoke of foreign rule and were living under the Hasmonean dynasty, celebrated on the holiday of Hanukka. The Hasmoneans had led a controversial overhaul of religious and political authority in Jerusalem, which may have led to the formation of the Qumran sect. This group believed that they alone were practitioners of divine truth, that the religion practiced and professed in Jerusalem was false and profane.

Authorship of the scrolls is contested among scholars, with some maintaining that they were in fact written by the Essenes, a Second Temple-era sect known to have withdrawn from urban society to live a life of purity and asceticism. The exhibit, however, does not explore the question of authorship, instead using the scrolls as a lens through which visitors can understand the circumstances that surrounded and formed them.

Rather than highlighting the people of Qumran, said Schiffman, “[the scrolls] are focused on an ongoing story”—a story that 2,000 years later still connects with people. The Hebrew Bible did, after all, lay the groundwork for three of the world’s major religions, and the scrolls in particular contain ideas that are similar to those of early Christianity.

Among the highlights of the exhibition is a three-ton stone from Jerusalem’s Western Wall, along with a scale re-creation of the wall itself in which visitors can slip notes to be eventually placed in the real Western Wall. There are also six ossuaries, found in a Jerusalem tomb, inscribed with the names Jesus, Mary and Joseph (common names in the Second Temple era) as well as the oldest-known version of the Ten Commandments—one of the scrolls (and a later addition to the exhibit).

But it is the scrolls themselves that are the real draw. As Schiffman noted, “The experience of being in a room with documents and scrolls from over 2,000 years ago” is one that goes unmatched.

Ray Katz works in digital production and lives in New York.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply