American View

Feature

Woodstock Values

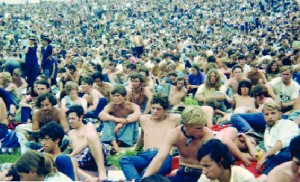

You may have walked by one on the street and never had a clue. Balding, paunchy and wearing a business suit, there’s nothing about these middle-agers to tip you off. But more than four decades ago, they spent a magical weekend reveling in the cream of the nation’s folk and rock music—and the mud—a moment in time that would go down in America as the Big One: Woodstock.

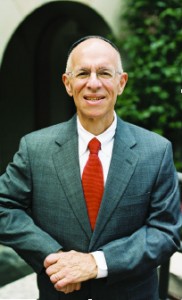

Geographically, Alan Cooper has not traveled that far away from Woodstock—actually Bethel, New York. These days, he takes the train from South Orange, New Jersey, to the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, where he is provost and a professor of Jewish studies.

Jeff Meshel has lived in Israel for 35 years, teaching English and theater at a Beersheba high school for 25 of them. Today, he telecommutes to a Tel Aviv high-tech firm where he is a technical editor.

What remains of his Woodstock experience?

Perhaps it is the blog Meshel posts on 1960s rock at www .jmeshel.com; evening rehearsals with a singing group; or his “living archaeological relic”—’60s music presentations to an awed group of Israeli teens.

But 43 years ago, Meshel and Cooper—and nearly a half million other hippies—had very different to-do lists.

Even the organizers of Woodstock—billed as “An Aquarian Exposition in White Lake, New York: 3 Days of Peace and Music”—could not have known that the upstate farmland would become the second most populated city in New York State August 15 to 17, 1969. Asked in a PBS interview about Woodstock, rocker David Crosby said, “…the important thing about it wasn’t how many people were there or that it was a lot of truly wonderful music…. The important thing was…that [a] generation of hippies looked at each other and said, ‘Wait a minute, we’re not a fringe element…. We’re what’s happening here!’’

That same year the Beatles released Yellow Submarine, the first humans walked on the moon and Golda Meir was sworn in as Israel’s first (and still only) female prime minister. It was a time of angry antiwar demonstrations and Chicago Eight arrests.

But for many of the tens of thousands of young Jews who made the pilgrimage to Woodstock, there was something vaguely Jewish about the experience. The festival celebrated ideals easy to label as hesed (lovingkindness), tzedek (justice) and tikkun olam (repair of the world), but were paraded under the banners of “sharing and caring,” “we shall overcome” and pursuit of peace.

Certainly there were Jews aplenty involved in every aspect of the festival. Organizers Artie Kornfeld, Michael Lang, John Roberts and Joel Rosenman were Jewish, as was Bethel dairy farmer Max Yasgur, who rented them 600 acres for $75,000.

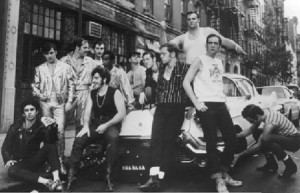

Jewish musical frontliners included Jorma Kaukonen (son of a Jewish mother) and Marty Balin (whose father was Jewish) of the Jefferson Airplane; Arlo Guthrie (his mother was Jewish); Country Joe and the Fish’s Joe McDonald (son of a Jewish mother) and Barry Melton; and Blood, Sweat & Tears’s Jerry Hyman, Steve Katz, Fred Lipsius and Lew Soloff. There were the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart and Bert Sommer and many in Sha Na Na, including Henry Gross, Elliot Cahn and Cooper.

Even the local Monticello Jewish Community Center played a part when it generously donated thousands of sandwiches to hungry festival-goers.

“There is a brakha you say when 600,000 Jews are assembled in one place,” says Meshel, 63. “There weren’t nearly that many at Woodstock, but there certainly were plenty of us.” He and his friend Bill Spear had just finished their junior year at the University of Cincinnati, and Spear’s ’68 Mustang was at their disposal. With two shoeboxes packed with chicken-on-halla sandwiches, apples and strudel courtesy of Meshel’s grandmother, they arrived Friday afternoon to the sounds of—silence.

Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Courtesy of Alan Cooper.

“All you could hear was the shuffle,” Meshel adds. “We were surrounded by other hippies, as we say in benching, ‘as the streams return to the Negev.’ In Cincinnati we felt like the ‘other.’ Now, all of a sudden, we were a critical mass. We were part of the Woodstock Nation.”

They stayed for folk-set Friday night, where the likes of Richie Havens, Joan Baez and, Meshel’s favorite, Arlo Guthrie, played through the raindrops. The friends crawled under the Mustang to stay dry; cramped and bleary-eyed, they left the next morning. “We were certainly uncomfortable,” Meshel recalls, “but also such musical purists that we preferred the pristine recording studio conditions to the live performance.”

Meshel notes that the 1970 killings at Kent State University in Ohio reminded him that America had another, angrier side. “When I saw the bumper sticker ‘America: Love It or Leave It,’ it was a message I could not ignore.” By the following spring he had made aliya with two suitcases and a box of record albums. “[In Israel,] I felt embraced, like I’d come home,” he says. Still, he would not have traded the experience. “How lucky we were to grow up in that generation, with incredible things happening not just musically but socially, spiritually and politically,” he says. “The truth is, we did grow up in legendary times.”

Woodstock veteran Sharon Klein, today a New Paltz, New York, real estate broker and singer-songwriter, lives close to the Yasgur farm. But 41 years ago she was a 15-year-old from Queens whose Woodstock junket left her with a sour taste—and a bad case of mono. “I was so sick I missed my brother’s bar mitzva,” recalls Klein, who sums up the festival as “miserable, disgusting and an open sewer.”

Yielding to their daughter’s determination to go, Klein’s parents braved the Friday traffic to drop her and two friends at the site, then checked into a boarding house in White Lake to await their return. Within hours, Klein had become separated from her friends and was watching young men setting their draft cards on fire as Joan Baez sang “We Shall Overcome.”

It was a night of aimless wandering and no protection from the driving rain. Just before dawn, a young man invited her into his tent where she slept soundly. “But I knew my mother would be terribly worried about me,” she says, so she set off on the seven-mile hike to her parents’ boarding house. Seeing their daughter caked with mud, they were more relieved than horrified.

“And you know what was kind of endearing?” Klein asks. “I was such a belligerent kid but my parents knew how badly I wanted to go so they took me.”

Klein returned to the Woodstock site last summer for a Sting concert at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, emerging with a new appreciation of that damp weekend. “The strange thing is you can still feel the vibe,” she says, “kind of like it’s sacred ground. Only now it’s pristine.”

It drives Joel Weinstein crazy that his wife, Sherry Adams Weinstein, went to Woodstock while he, who had played studio backup for the Animals and Sha Na Na, was stuck doing gigs back in New York City.

“He always says, ‘You are the last person in the world to be at Woodstock,’” says Weinstein. She was studying fashion design at New York Technical College when her friend Shelley Habif called to say she had ordered their Woodstock tickets and booked a motel room in Bethel. After hours of gridlock on the New York State Thruway, Habif’s mom told the girls (including Habif’s cousin) they would be walking the rest of the way. Fifteen miles later, they arrived to hear Richie Havens kick off the festival.

But the rain grew more insistent—and the cousin was lost to a fellow she met. The hike was the last gasp for Weinstein’s high heels (luckily, she had also brought sandals along). They went to their motel room, where they found a young woman asleep in their bed and joined her.

By morning, they went back to the site to look for Habif’s cousin when they heard approaching helicopters. “We looked up to see an amazing sight: cans of soda and water dropping from the sky.”

After the Saturday morning set the friends resolved that, cousin or no, they needed to head home. “I kept looking for guys with a Jewish star or hai, thinking maybe a nice Jewish guy would be willing to give us a ride,” Weinstein recalls. At long last, they found someone who drove them to Scarsdale in his flower-decaled Volkswagen. From there they hitchhiked for the first time ever.

Fashion is still Weinstein’s thing—she owns Selections, a Framingham, Massachusetts, boutique. Her high heels are long gone, but she still has her Woodstock tickets.

But not everyone at Woodstock suffered deprivation. Just ask Cooper; food—even champagne—was abundant if you were on the other side of the stage, he says. Today, Cooper’s students at JTS seem to know he was Sha Na Na’s lead singer at Woodstock. They easily spot him in the film Woodstock or on YouTube. He’s the guy doing the twist in the gold vest, shades, chest hair and black cap in “At the Hop” at dawn on Monday.

“I looked totally stupid,” Cooper says good-naturedly. It was minutes before Jimi Hendrix would close the festival with his now classic “Star Spangled Banner.”

Cooper and his friends at Columbia University were performing at a New York club earlier that summer when Michael Lang came by to catch their oldies act. They agreed to his terms: $700 for the 12 of them, signing away all recording and film rights. With performer passes, band members were treated royally, including hanging in British blues band Ten Years After’s food-packed van. “Looking out at the crowd was almost impossible to believe,” he says. “Of course, none of us had the brains to bring a camera. That was the kind of thing our parents did.”

By the time Cooper played Monday morning, the crowd had diminished to about 50,000. Still, their appearance in the movie and album transformed the band into a household name. True stardom would come with the Sha Na Na television show years after Cooper left the band for academic pursuits, but he was in the group long enough to perform on their first album, Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay and on The Tonight Show and The Merv Griffin Show.

“I never intended the world of rock ’n’ roll to be my life’s work,” he says. “It was fun, but then the time came to get on with my real life….” Cooper went on to earn a Ph.D. degree in biblical studies at Yale. “But mostly I feel lucky to have been there,” he adds. “Woodstock was a defining moment of our generation, though my kids think it’s amazing—and amusing—that their dad was…there.”

Forty-three years later, historians and sociologists still debate whether Woodstock marked the end of the era of peace and love or its pinnacle. That December, a Hell’s Angel stabbed a man to death at a rock concert in California and, by spring, National Guardsmen had killed four students at Kent State. Slowly, mainstream culture absorbed hippie tie-dye clothing, its music and drugs.

It was a generation in search of meaning, says Meshel: “Bill became a guru, another friend turned to the bottle. Me? I got religion.”

And Klein, despite her discomfort, ticks off Woodstock’s blessings. “I learned there are people who would feed a stranger who’s hungry, “ she says, “even when they didn’t have much themselves, and take you into their tent if you need a place to sleep. Our generation was very magical…with an idealism that a lot of us still carry with us.”

Looking back, Weinstein says, “Woodstock was totally heimish. In the rain and heat, everyone helped each other, and when I got home there was a kind of pride. If everyone would treat each other like we did at Woodstock, my God, what a better world.”

“You always know when you’re in a liminal moment,” says Cooper. “You can feel you’re crossing a threshold and you know everything is going to be different afterward…. It’s a split second in life that gives rise to a mix of hope and uncertainty. That, in a nutshell, was Woodstock.” H

The Museum

The Museum at Bethel Woods Center for the Arts (www.bethelwoodscenter.org; 845-583-2000) in Bethel, New York, on the site of the 1969 Woodstock festival, is a monument to an era of social, political, cultural and musical change and offers educational dialogue about peace, equality, the environment and social responsibility. Multimedia and interactive displays and artifacts (right) are on permanent display. Included are performance clips and stories from and about iconic rockers, the civil rights movement, the space race, the cold war and the counterculture. Interactive exhibits allow viewers to immerse in the sights and sounds of the festival. An April 1 to July 22 retrospective includes the work of Jewish artist Arnold Skolnik, who created the famous Woodstock peace and music poster.

The Trip

Teetering on the precipice between high school and college, I was 17 when my little sister, Tobi, and I pooled our money and bought tickets to the mythical-sounding weekend. Thursday morning we climbed into a friend’s aged Peugeot, hoping to trade the heat of Silver Spring, Maryland, for cool green fields.

I recall the dazzling clarity of the stars that night as we unrolled our bags on a quiet hilltop. But even in the dark, we sensed that this was bigger than a weekend of music amid the cow pies. In the morning, the final touches were hammered onto the scaffolding and Tobi and I admired the silver jewelry, musk oil and leather belts for sale as well as the guys diving like young otters in the pond.

By Friday afternoon, there were tents and blankets everywhere and news helicopters circling overhead. Soon the stage burst into life, Richie Havens’s “Freedom” echoing off the hills, and Joan Baez’s “Ballad of Joe Hill,” a lullaby for the sleepy children in this never-never land. The rain started gently at first.

We watched a naked old man with long white hair saunter by with his sheep as nightfall upped the drug ante. When some of the kids’ acid trips turned terrifying, we heard their screams from the medical tent. It was the only moment when I felt truly afraid.

By midnight, when everything was soaked through, we were invited into a pup tent belonging to kids from Long Island. Slabbed sideways, we slept to the sound of raindrops on canvas.

The next morning, en route to the Greyhound bus, we encountered angry glares from behind blinds and car windows. But the locals I remember best defied stereotypes. There was a couple who set up a picnic table piled with peanut butter sandwiches and pitchers of lemonade. Welcoming us to eat and use their bathroom, they invited us to call our parents from their kitchen phone. Even later, after we were harangued by the bus driver (“Who gave you kids the right to screw up this town?”), it was that couple’s kindness I remember best.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply