Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: A Walk in the Park with Marc Chagall

Perhaps the most surprising, and telling, images in “Chagall” an exhibit of works by famed 20th-century artist Marc Chagall, curated by Constance Schwartz at the Nassau County Museum of Art in Roslyn Harbor, New York, and running through November 4 (www.nassaumuseum.org), are the two that open and close the displays on the main floor. The former, The Finding of Moses, is a small 1930 line drawing (graphite on wove tracing paper) of baby Moses in a basket, the Egyptian princess standing nearby. The latter is a larger dramatic work entitled Job (gouache on paper). According to the wall text, Chagall worked all day in his studio on Job—it was his last work and he died that same evening, March 28, 1985. In the picture, Job’s wife is supporting the limp body of her suffering husband, telling him (as in Scripture) to “Curse God and die”—which he refuses to do. Accompanying Job at the last stage of his life are: a figure holding scriptures, a crucifixion, the city of Jerusalem, a mass of fellow villager reaching out to him and the angel Gabriel, who brings good news. This symbolically rich painting not only personifies Chagall and connects the artist to his biblical sources, it expresses his lifelong belief in an optimistic faith (the colors, however, are relatively muted in blue, purple, green and red).

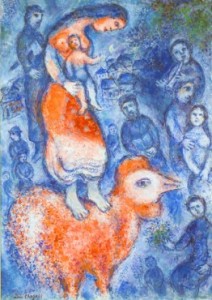

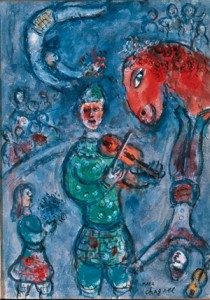

Although the majority of the other works in the four galleries on the first floor are representative of Chagall’s signature styles and boast his familiar icons—reclining nude lovers, brilliant flowers, rich colors, fabulous circus entertainers, voluptuous women, Jewish peasants in Vitebsk, fantastic floating images, various animals—these two works demonstrate Chagall’s intense and lasting interest in the Bible. They also introduce viewers to the second part of the exhibit, which fills the second floor of the museum: a series of hand-painted biblical etchings that Chagall began in 1932 and only completed in 1957.

New York/ ADAGP, Paris.

The seven galleries in the museum, once a mansion where poet and editor William Cullen Bryant lived, are labeled to help guide visitors chronologically through the displays. A downstairs hallway has a long horizontal timeline of Chagall’s life beginning with his birth in 1887 in a suburb of Vitebsk, the village he would affectionately memorialize his entire life.

The first gallery (1917 to 1949) gives some background on Chagall’s transformative first stay in Paris, where he lived from 1910 until 1914, when World War I broke out. He studied the Old Masters at the Louvre and viewed the avant-garde work of contemporary artists at galleries, some of whose styles—such as the geometric techniques of Cubists and rich colors of Fauvism—he integrated into his own work. But mostly, Paris is the city where he became an Expressionist (some would say he helped birth Surrealism). According to the wall text, Chagall came to Paris, he said, because of the light: “I was very dark when I arrived in Paris. I was potato colored, like Van Gogh, Paris is light and bright.” After the war, he returned to Russia, where he established an Academy of Art and Museum. In 1923, he returned to Paris.

Altogether, the 50 works on the first floor vary between nostalgia and love for home and family, celebrating the fantastic and romantic as well as depicting suffering, some of it in his crucifixion pictures. In those controversial works, Chagall, who saw himself as a citizen of the world, perceived Jesus as a great man, a prophet and a symbol of universal—and Jewish—suffering.

Two early works honor two of Chagall’s living places. House in Vitebsk, 1917 (oil on paper on canvas), shows the exterior of his beloved town: A wooden gate on a dusty road is entry into a quiet, peaceful village of wooden houses and a light post. Les chardons, 1931 (oil on canvas, laid on board), reflects the winter Chagall spent in the Alps: The interior of an eating nook is brightened, dreamlike, by the light of a haloed moon on the white tablecloth, in tones of white, gray, blue and turquoise. It is a cozy setting with a glass, book and vase with flowers.

La calèche fantastique, 1949 (gouache and pastel on paper), takes another look at Vitebsk, this time when Chagall returned to Paris after spending the war years in New York. Chagall’s fiddler on the roof—a wandering Jew in exile—floats before an intense orange ball of the sun. The musician (who represents Chagall) is joined by a fantastical, upright green donkey-like creature harnessed to a wagon pulling peasants.

New York / ADAGP, Paris.

A later work, Le bouquet sur le toit, 1968 (brush and ink, pastel, oil and gouache on paper), shows the continued pull—and love—of Vitebsk. The centerpiece of this color-saturated picture is a red vase atop a red-roofed house with red flowers amid the green leaves against a blue and purple sky, bird and goat; a mother and child and other characters surround the vase.

Another large work set in Vitebsk, also in red, from 1968-71, Le village fantastique (oil on canvas), feels joyous and mystical. It is replete with a man (Chagall?) riding a diving bird, a smaller man holding a globe standing on another bird, a mother holding a child, a goat looking on. The largest, mysterious figure has a head with an onion-shaped eye and is wearing an aproned skirt decorated with planetary shapes.

For variety, the exhibit includes The Good Samaritan, 1967, a reproduction of an arched leaded stained-glass window that is one of a series of nine in the Union Church in Pocantico Hills, New York. It was commissioned by the grandchildren of John D. Rockefeller Jr. in his honor. (In addition to those in Hadassah Hospital’s Abell Synagogue, Chagall created stained-glass windows for churches in France, Germany and Switzerland and one at the United Nations headquarters in New York.)

Chagall’s work on theater sets and costumes is represented by Design for Gogol’s Play: The Marriage, 1918-1919 (watercolor, gouache and pencil on paper). This Cubistic stage-set has a purple background that divides the players from the upside down background scenery.

In Paris, Chagall received several commissions from art dealer Ambroise Vollard. The first was to create illustrations for a two-volume series based on Oriental stories (Fables of La Fontaine; Tériade); the second was a circus series (Cirque Vollard), several of which are in this show (Femme Ane depicts a voluptuous woman with a head of a donkey).

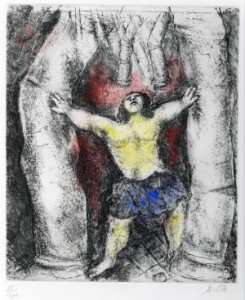

It is the third assignment that makes up the remainder of the Chagall display in the museum’s upper three galleries and hallway. Chagall worked on the Bible series—which is comprised of 105 plates, with 50 on display—through the 1930’s. By 1939, he had completed 66 of the hand-colored plates. Then World War II broke out and he moved to the United States. After he returned to France, he resumed work on the series, finishing it in 1957. The display is on loan from the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art of Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and was published by Édition Tériade. It is only the second time the Bible series has been shown in New York. (Previously it was exhibited at MOBIA, the Museum of Biblical Art, in New York.)

In contrast to the brilliant colors bursting forth from the works on the first floor, these mostly black and white etchings are delicately touched with soft colors—yellow, blue, pink, green, orange and rose. Beginning with The Creation of Man (a loving God carrying his creation the way a parent carries a child) to the Crossing the Red Sea (a winged angel leads the Israelites); from Joshua Armed by the Angel of God (a forceful angel encourages the new leader) to The Vision of Isaiah (an angel tells Isaiah that God is choosing Israel), the etchings are to be appreciated not for daring artistic innovations but for their storytelling.

Whether the crowds that are filling the Nassau County Museum of Art are coming to see the Bible through Chagall’s eyes—as poetry or spirituality—or to find joy and humanity in Chagall’s floating brides, lovers and acrobats, there is no question that the beguiling artist is charming his audience.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply