American View

Our Urgent Search for Non-Jewish Allies

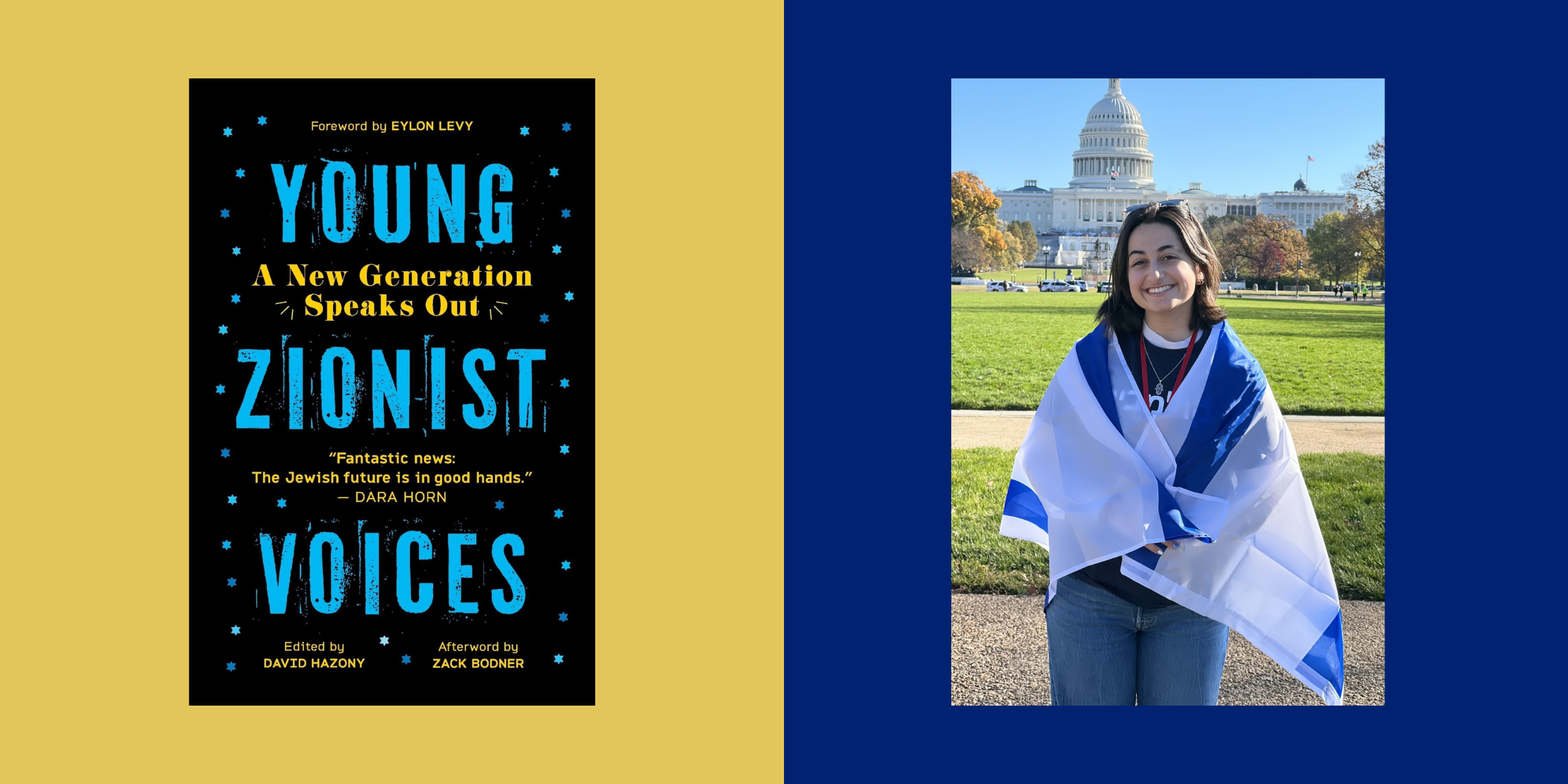

On college campuses around the world, there is a new bully in the yard. The name-calling, threats, intimidation and physical violence are not exactly new, but in the Campus Tentifada, the bullies have asserted their presence,” Eylon Levy, head of the Israeli Citizen Spokespersons’ Office and host of the Israel: State of a Nation podcast, writes in the foreword to the recently published Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out, edited by David Hazony, an Israeli writer, translator and editor.

“Like antisemites throughout history, they are driven by a moral zeal, a conviction that excluding Jews is the noblest expression of virtue. From colleges to workplaces to city streets, the bullies feel they have the license to scare Jews, to shout them into submission. But there is one thing they did not take into account: You can pick on the Jews, but the Jews are no longer easy pickings.

“The young writers, thinkers and activists appearing in this collection are not simply Gen-Z. They are ‘Gen-Zionists’: a new generation of Jews who understand this historical moment. Gen-Zionists stand up to bullies. They refuse to be intimidated. They will not let anyone shame them for who they are. Around the world, young Jews are mobilizing to show antisemites that Jews fight back, Jews answer back and Jews have each other’s backs.”

“Exactly one month after October 7, David Hazony published an essay in Sapir Journal called The War Against the Jews. ‘Stop acting like the benign ocean water that fuels the hurricane passing overhead,’ Hazony writes. ‘Instead, be the hurricane.’ Little could he have imagined that a song titled ‘Hurricane’ would, months later, at the Eurovision Song Contest in Sweden, become one of the defining texts of this era. There, Israeli Gen-Zionist heroine Eden Golan conquered Europe’s biggest stage despite the braying mobs determined to silence her.”

The essayists in Young Zionist Voices, which Hazony compiled and edited, “are the hurricane.”

In his own introduction to Young Zionist Voices, Hazony writes that the goal of this collection of essays is “to showcase a new generation of Jewish thought leaders” who are “calling for new ideas about everything being Jewish entails. Zionism for them is no longer just a political-activist position; it is a central pillar of the Jewish future.

“What they all share is not just an unflinching commitment to a flourishing Jewish people continuing far into the future, but also a creativity and dynamism that have been lacking in the Jewish discourse—an inner optimism that transcends the fear and pain which has, it seems, engulfed the conversations of older Jews.”

With thought leaders like these, he writes,“the Jewish future is in far better hands than many have come to believe. In their light, it is hard to be a pessimist.”

One of those thought leaders is Talia Bodner, whose essay follows.

On the morning of October 7, when Hamas showed the world exactly what the rallying cry “From the River to the Sea” looks like in practice, that genocidal slogan took off like wildfire on college campuses around the world. Fewer than five days after the October 7 attack, before Israel had even begun a significant military retaliation, thousands of my peers at Columbia University flooded the campus to protest against Israel’s right to defend itself—or more accurately, against Israel’s right to exist.

Immediately, teachers and other adults on campus reassured me that, while the voices of the anti-Zionists and antisemites may be loud, they are not the majority, and in fact represent only a tiny fraction of the population as a whole.

But while this might be the case for their generation, it does not feel true for mine. My parents and my friends’ parents received messages of love and support from their non-Jewish community members, expressing condolences and condemnation of what happened to our Israeli friends and family. I, on the other hand, did not receive a single text from my non-Jewish friends. Not one.

On November 14, 2023, when I stood before hundreds of thousands of people and spoke at the March for Israel at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., I felt immense gratitude for the ability to be in the presence of so many Jews. And still, I felt a deep sense of dread. Because I knew that while I was surrounded by so many Jews, there were so few non-Jews standing with us. Everyone around me was so impressed at the non-Jewish allies who spoke up at the rally to condemn Hamas and to advocate for Israel’s right to exist and to defend its people. And yet, all I could think was: Not one of them is my age.

In 2017, my Jewish friends and I marched in our pink hats alongside feminists from every generation and background. In 2018, I rallied with my peers from Jewish day school for gun safety, alongside students and their families from every school district and neighborhood. Then in 2020, my Jewish friends and I joined our African American peers in Black Lives Matter protests around the country.

My identity has been shaped by my efforts to be an advocate, a friend and an ally. In every movement of activism, I stood among friends of different races, religions, genders, sexualities, nationalities, ethnicities and ages. But in November 2023, I looked around at my peers and found myself standing among Jews only. Now, in our moment of great need, young Jews were left advocating alone.

College is the place where young people have the opportunity to develop and solidify their opinions, where we learn to build up our voices to become strong leaders. People tell me again and again that while these anti-Israel protests might sound the loudest, they are not the majority. But if we don’t act now, then they will be soon enough. And if we continue on this path, the voices yelling in colleges will be yelling in positions of authority in industry, in culture and in the halls of government.

Children are taught nowadays to be neither a bully nor a bystander. My generation has been raised to be active upstanders; we are a generation bred for activism. So why, when an Israeli student on my college campus hangs posters of innocent civilians who are being held hostage, and then gets beaten with a stick, does no one stand up? Why, when a student posts on a school-specific social media platform, calling for all Israel Defense Forces veteran students to “die a slow and painful death,” is it reposted, instead of reported? And why, when a Columbia student makes a video saying, “Zionists don’t deserve to live,” or “Be grateful I am not just going out and murdering Zionists,” do people not see why it’s the least bit problematic?

Jewish and Zionist students on college campuses are crying out for help, screaming into a void, only to be met with a tsunami of antisemitism and hate. The voice of young Jewish Zionists on campuses is louder than ever before, and still—in our generation of intersectionality, allyship and activism—we Jews are left standing alone. And as more and more “woke” Jews turn against their Zionist brothers and sisters, we Zionist youth who are standing up for ourselves are left with no allies.

Sadly, it seems like we are the only ones noticing.

So, how do we address what might be the single most important challenge for the young Zionist movement in America today: our lack of allyship?

One option would be to abandon our search for allies and to continue standing alone. We can adopt the bootstrap mentality of self-reliance: Only Jews are responsible for Jewish self determination, autonomy and auto-emancipation. And in some ways, when we do succeed, isn’t it even more gratifying to know we were able to do it ourselves?

Perhaps. But that is a big risk that could have disastrous consequences if it is not effective. So, while the Jewish people are a mighty nation, we are too tiny to overcome our challenges without allies. Just as Israel needs allies to stand alongside her in an international community that often seems out to get her, so, too, must we rely on the support of others to help us overcome the challenges of our adversaries. And that means we must continue to work to build allies.

So now the question is: What are we looking for in an ally? For starters, we need people who will amplify our voices rather than trying to speak on our behalf. But this, in turn, raises the question of how the beliefs and political opinions of potential allies affect our ability to collaborate with them on this issue. If we are truly going to recruit allies who will be there for us in our moment of need, then we must cultivate them from the left and the right, from both liberals and conservatives.

But that gets complicated, especially on campus. On the one hand, it has been reassuring to see leaders on the right who have advocated for American support of Israel. However, as a progressive young woman, I often find it uncomfortable to be in conservative political spaces. I often have to check my other values at the door; I don’t see eye-to-eye with them on so many other social justice issues like LGBTQ+ rights, gender equality, climate change, reproductive rights, racial equality, gun safety and the separation of church and state.

Sometimes, I even question whether our conservative allies are really advocating for us for the right reason. I worry when leaders of the radical right, some of whom have been known to promote antisemitism, support Israel’s war against Hamas. Are they supporting Israel because they believe in the justness and morality of the Jewish state, or because they hate our enemies more than they hate us right now? What happens when the war ends? Can these leaders remain our allies when the radicals among them fall back into antisemitic tropes like “Jews will not replace us?”

On the other hand, even if we can maintain our relationships with the conservative right, we may risk alienating our friends on the progressive left. For years, we had allies on the left because progressive leaders valued our intersectional identities. But now, progressive intersectionality has begun to exclude not only Zionism, but more and more, it seems no longer to include Judaism, either. When champions of social justice spew anti-Zionist and antisemitic hate speech in their efforts to delegitimize Israel, I find it hard to imagine a world in which we are ever able to rebuild those relationships.

And yet, surely, we must try. Right?

There was a time when we could engage in healthy discourse across the picket line, with diverse perspectives and opinions. When Israel and Hamas went to war in the spring of 2021, I was a junior in high school and the president of my school’s Jewish Student Association. When my progressive friends would post slogans on social media that were hypercritical of Israel, I found myself immersed in deep and difficult conversations about the complexities of the war, the nuances of the region and the righteousness of Israel’s struggle. After such conversations, my friends almost always stood by me.

Only three years later, in the wake of Israel’s war against Hamas, some of those people who were once my closest friends won’t talk to me. My high school best friend blocked me on October 7, the moment I posted “My heart is in Israel.” It seems dear friends would now rather completely ignore me than have a conversation about our differences of opinion. So yes, it’s disheartening and challenging, but I still believe we need to keep trying to find people willing to have the tough conversations.

Some of us will continue to reach out to our former allies on the progressive left, and we need those people not to give up on those friendships. Others will turn to the conservative right and attempt to build stronger relationships there—and we need those people to cultivate new allies as well. Still others will choose to go it alone, and we need those people’s valiant efforts to continue to strengthen our collective resolve. The question of which path to take is arguably the hardest and yet most important choice every young Zionist will inevitably have to make.

The truth of the matter is, I have seen people with whom I agree 99 percent of the time willing to drop me on a dime over the one thing we can’t agree on. And if I expect them to work harder at maintaining our friendship despite our differences, then I must be willing to commit to the same. It has become increasingly important to embrace the discomfort of disagreement in order to break the cycle of intolerance that our society has fallen into. We must be able to make space for people with opposing viewpoints and continue to engage them intellectually. And we have to remember that sometimes, we need to be able to check partisanship at the door so we can sit down and find our common ground.

Whichever path to allyship we decide to follow, one thing is clear: If we don’t choose for ourselves, the decision will be made for us. And we will continue to struggle alone.

Talia Bodner is a student from the San Francisco Bay Area who is studying in the joint program between Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City. An alumna of Young Judaea, she spent a gap year on the movement’s Year Course in Israel, where she interned in the Knesset and volunteered teaching English to Israeli Arab students.

This essay, and the introduction, were adapted and excerpted from Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out (Wicked Son). Edited by David Hazony. Copyright © 2025 David Hazony.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply