Food

An Ethiopian ‘Mouthful’ From Beejhy Barhany

Beejhy Barhany would love to feed you with her own two hands. “Silverware is so cold and clinical,” the Ethiopian-Israeli-American chef told me by phone from her home in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood. “The hands are the first tool that was given to us by nature, and the best way ensure a point of connection. If I want to show you hospitality, I am going to offer you the best morsel I’ve got straight from the tips of my fingers.”

It’s a concept central to Ethiopian food culture known as gursha (“mouthful” in Amharic), which Barhany also chose as the title for her tantalizing new cookbook, Gursha: Timeless Recipes for Modern Kitchens, from Ethiopia, Israel, Harlem, and Beyond, scheduled to be released on April 1. Barhany, owner of the vegan and kosher Tsion Cafe in Harlem, sees the book as a vehicle to extol the virtues of Ethiopian food to a wider audience.

“A lot of people think that it’s only spicy food, or a lot of raw meat, or that it’s all vegan,” said the 48-year-old, who parents two teenage children—daughter Alem and son Berhan Ori—with her husband, Padmore John, who grew up on the Caribbean island of Dominica. “We’re talking about a now-trendy but ancient cuisine rich in health benefits, vegetable-forward and very delicious.”

Barhany also documents in the book her dramatic childhood years and the larger story of both her family and people—the Beta Israel, as Ethiopian Jews are known. Co-authored with food writer Elisa Ung, Gursha spans generations and continents, returning again and again to the Beta Israel’s enduring love for Judaism and Israel, where the chef’s extended family remains and which she visits frequently.

RELATED READING: Israel’s Ethiopian Culinary Luminaries

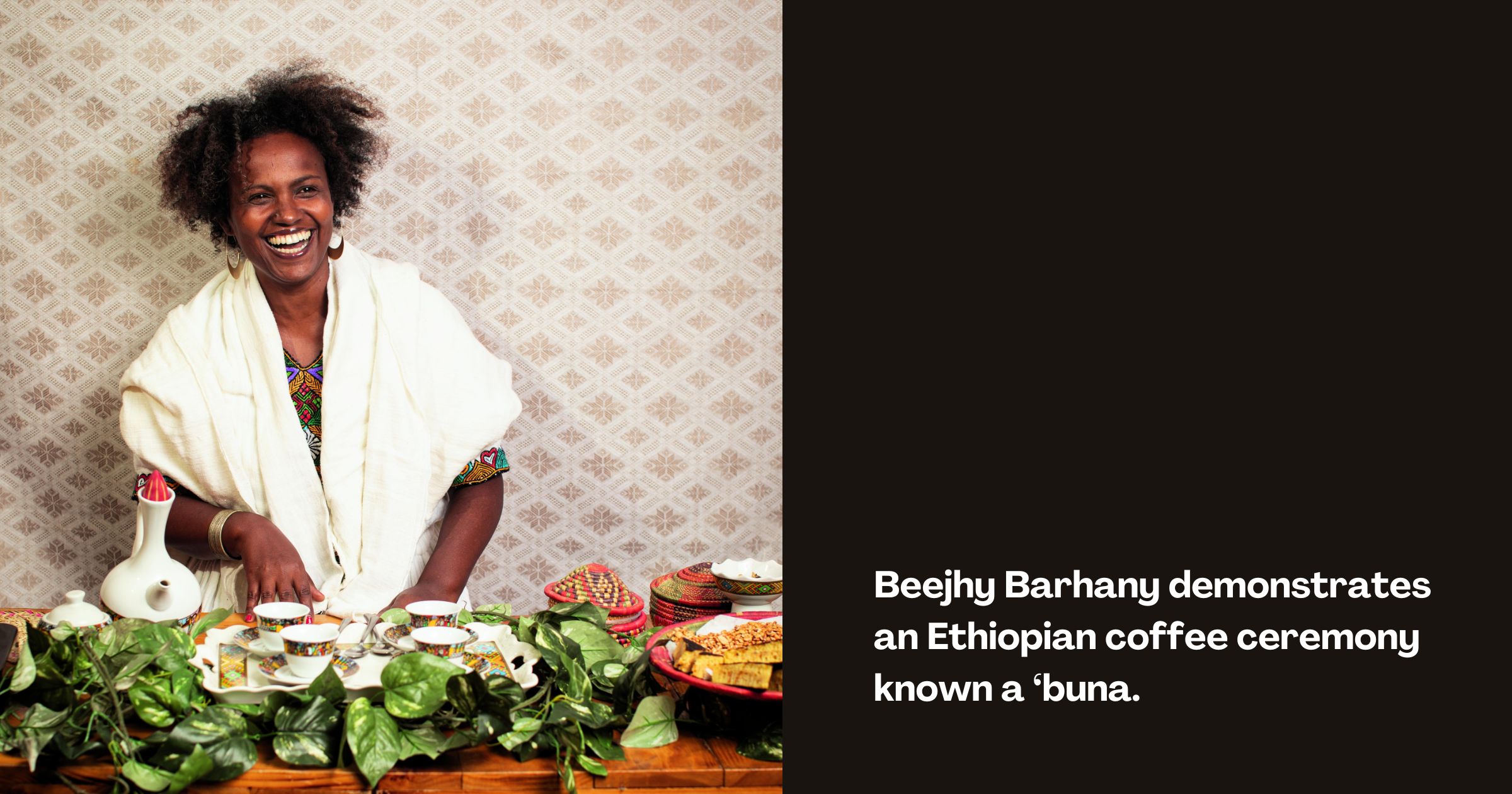

Barhany’s story begins in fertile Tigray, Ethiopia, where she was the beloved first grandchild of her generation, given free rein to scamper among fields of pumpkin and wild greens on her family’s land. Her mother, Azalech Ferede, would start every day by roasting potent green coffee beans for the Ethiopian coffee ceremony known as buna—the Amharic word for coffee.

Ferede would prepare for Shabbat by making dishes like the berbere-spiced chicken stew known as doro wat (see accompanying recipe) and fragrant dabo bread—the Ethiopian Jewish version of challah—that she’d serve to her young daughter with milk and honey to remind her to continue yearning for Zion.

But her idyllic childhood ended abruptly. In the immediate years after the assassination of dictator Haile Selassie in 1975, violence broke out all over the country, creating an unstable environment ripe for discrimination against the Beta Israel. In 1980, Barhany’s community, though forbidden to leave Ethiopia, traveled in a caravan of 300 people under the cover of darkness, loading everything they could onto their horses and carts. They eventually bribed their way past the Sudanese border to the northwest, where they met other Beta Israel refugees who eased their arrival. Still, the next two years in Sudan were tense. Unable to reveal their Jewish identities, they observed Shabbat and kashrut in secret, though they had warm relations with their Muslim neighbors.

Eventually, Barhany’s cousin, Ferede Aklum, known affectionately as “The Moses of Ethiopia” for his role working with the Mossad to squire hundreds of Ethiopians through Sudan on their way to Israel, smuggled the family via Uganda and eventually Kenya. After a few weeks on the move, they finally flew to Israel on their own, not as part of one of Israel’s airlifts that brought tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews to Israel beginning in 1984.

Though everyone kissed the ground on arrival, once they moved into an absorption center, the family experienced their first reality check. Many Israelis had never seen a Black Jew, and Barhany and her relatives were forced to undergo official conversion in Israel. “That hurt, because we were far more ritually observant than the majority of Israelis,” she recalled.

Once the family settled in the southern coastal city of Ashkelon, Barhany adjusted well to school, eschewing her own cuisine and leaning hard into Israeli staples like chocolate spread and schnitzel. Living during her teen years in the Gaza envelope on Kibbutz Alumim—where she worked and studied—cemented her love of nature as she made friends from around the world.

When she returned from her post-army trip around the world in 1999, the Ethiopian community was beginning to push back against what it believed was institutionalized discrimination in military and professional settings.

“Racism is everywhere,” said Barhany. “Israel is the country that molded me to be who I am, but I have a very strong opinion about the integration of cultures there. We can’t sweep it under the rug, and I want it to be a better place for Jews of color and Black Jews. I don’t want to hear, ‘This is typical.’ Treat people as human beings in order for people to live harmoniously in the land of the Jews.”

In 2000, Barhany moved to New York, a city that had besotted her during her backpacking travels. In Harlem, she felt at home, celebrating the richness of Black culture and creating a community with other Ethiopian Jews, who in all of America number around 2,000. To quell homesickness and remain connected to her ancestry, she began recreating her family’s treasured recipes, eventually realizing that food was both a grounding influence and a potential career path.

It also became an outlet to promote Ethiopian culture among other Jews.

“I first met Beejhy over a decade ago when I was writing an article about Ethiopian Jewish food,” recalled Leah Koenig, the author of several best-selling Jewish cookbooks, most recently Portico: Cooking and Feasting in Rome’s Jewish Kitchen. “She invited me to her apartment in Harlem, and we cooked together—doro wat and kik wot—and I remember how welcoming she was, how vibrant her personality was and how passionate she was about her cuisine and culture.”

Barhany opened Tsion Cafe in the former home of Jimmy’s Chicken Shack, a legendary jazz club, in

Harlem in 2014. In addition to a full complement of Ethiopian breads and stews, she put Nigerian jollof rice on the menu to honor Pan-African culture; braised fava beans as a paean to a dish she loved during her time in Sudan; and her signature shakshuka.

“We are educating people about Jewish and Black diversity and inclusion through the food during a new Harlem renaissance,” Barhany said. “After they come, they leave intrigued, happy and satisfied. We want to engage and attract all people and walks of life and instill dialogue and respect.”

That has proven to be more of a challenge since the Hamas attacks on October 7. “My heart was broken,” Barhany said. “It is devastating, and I pray for peace and coexistence.”

Tsion Cafe has been added to boycott lists, and its entrance was vandalized with a swastika drawn on its awning. “We’ve been called ‘dirty Jews,’ but this existed even before that day,” she said. “There are people who hate for no reason.”

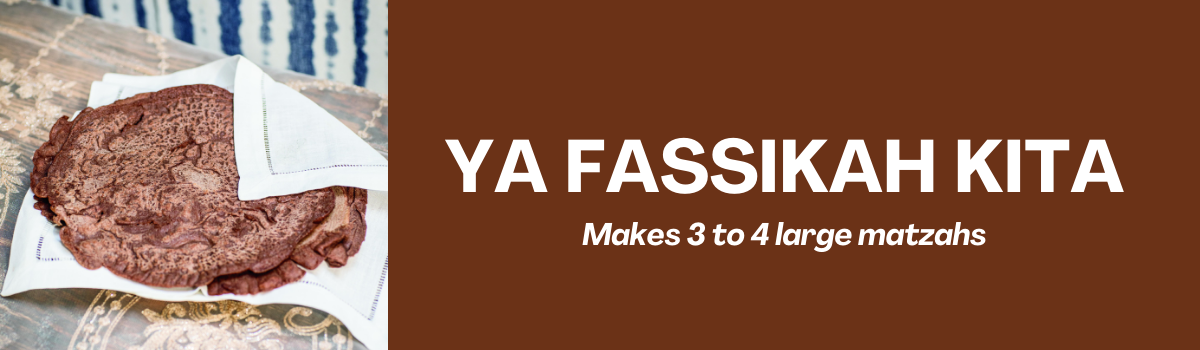

Countering that hate with positivity, hospitality and Jewish pride has become even more important to Barhany. In Gursha, for instance, she showcases Shabbat and holiday traditions through rich text and photographs. The book also features Passover-friendly recipes like the accompanying one for matzah, Ya Fassikah Kita, which uses the Ethiopian staple teff flour—considered kitniyot and therefore off limits to some Jews during the holiday.

In contrast, her seders, she said, are simple affairs that focus on family and storytelling rather than a lavish table groaning with sumptuous food. “Passover is about the journey from slavery to freedom, literal and spiritual,” Barhany said. “That’s what we’re always striving to remember.”

Ya Fassikah Kita

Ingredients

- 1⁄2 cup ivory teff flour

- 1⁄2 cup brown teff flour

- 1 teaspoon fine sea salt

- 2 cups lukewarm water

- 1 tablespoon vegetable oil (omit if using a nonstick pan)

Instructions

1. In a large bowl, use your hands to combine the teff flours, salt and lukewarm water, breaking up clumps of flour, until smooth.

2. Warm a 12-inch skillet over high heat. If the skillet does not have a nonstick coating, add the oil and swirl to coat the pan.

3. Pour 1 cup batter into the center of the pan and use the bottom of a ladle to spread it over the surface of the pan. Cook until dry on top, about 3 minutes. Push a wide spatula underneath the matzah and carefully flip it over. Reduce the heat to medium-low and cook until the matzah is completely cooked through, about 3 minutes.

4. Repeat with the remaining batter. Serve immediately.

Doro Wot

Ingredients

- 2 pounds chicken drumsticks (8–10), skinned

- 2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

- 1 tablespoon fine sea salt

- 8 large eggs

- 6 cups kulet (recipe follows)

1. In a large bowl, combine the drumsticks, lemon juice and salt. Add cold water to cover and swish the water around to mix. Soak for at least 10 minutes and up to 1 hour.

2. Prepare a large bowl of cold water and ice and keep it nearby. In a medium pot, combine the eggs with cold water to cover. Bring to a boil over medium heat and cook the eggs for 8 minutes. Remove the eggs from the pot and place in the ice bath until completely cooled.

3. Peel the eggs, leaving them whole. Make four shallow, evenly spaced cuts from top to bottom on each egg, scoring the white but stopping at the yolk.

4. Meanwhile, in a large pot, heat kulet over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until simmering.

5. Drain the water from the drumsticks. Wash the drumsticks well under running water, massaging the chicken and rinsing several times.

6. Submerge drumsticks in the kulet. Bring back to a simmer and cook gently, stirring occasionally and reducing the heat if the sauce begins to boil, until the drumsticks are completely cooked through, 25 to 30 minutes. During the last 5 minutes of cooking, add the eggs and gently stir to completely submerge them in the sauce. Serve warm.

Kulet

Ingredients

- 10-12 large yellow onions, peeled and quartered

- 6 cups vegetable oil, plus more if necessary

- 2 cups berbere (available in some groceries, or recipe follows below)

- 4 teaspoons minced garlic

- 2 teaspoons minced fresh ginger

- 3 tablespoons fine sea salt

- 8 cups hot water

- 6 ounces tomato paste (or 12 ounces, if you prefer less heat)

- 1 tablespoon ground cardamom

Instructions

1. In a food processor, puree the onions until smooth.

2. Pour the onions into a large pot and bring to simmer over high heat. Cook, stirring occasionally and reducing the heat if the onions begin browning, until most of the water has evaporated, 35 to 40 minutes.

3. Stir in the oil and simmer for about 5 minutes to incorporate. Stir in the berbere, garlic, ginger and salt. The mixture should be moist; if it appears dry, add more hot water, about 1/2 cup at a time. Cover the pot and cook over medium heat until the mixture has taken on a red hue, for another 10 to 15 minutes.

4. Add the hot water and tomato paste and stir well. Bring to a simmer, then reduce the heat and cook uncovered, stirring occasionally, until the flavors blend and the stew base becomes fragrant, about 1 hour.

5. Remove from the heat and stir in the cardamom. Let cool.

Berbere

Makes about 2 1/2 cups of spice blend

1 cup paprika

1/2 cup cayenne pepper

3 tablespoons ground cardamom

2 tablespoons ground ginger

1 tablespoon onion powder

1 tablespoon ground coriander

1 tablespoon ground cumin

1 tablespoon black pepper

2 tablespoons fine sea salt

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cloves

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1 1/2 teaspoons ground nutmeg

1 1/2 teaspoons ground fenugreek

In a small bowl, mix all the ingredients together and transfer to an airtight jar. Store at room temperature for up to 6 months.

Adeena Sussman lives in Tel Aviv. She is the author of Shabbat: Recipes and Rituals from My Kitchen to Yours and Sababa: Fresh, Sunny Flavors from My Israeli Kitchen. Sign up for her newsletter here.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Michele J Probst says

I would like the recipe for Gingery Swiss Chard mentioned on p. 42 of the March/April 2025 issue. It said it was available on hadasahmagazine.org/food but a search for the recipe came up empty. Can you please provide?

Arielle Kaplan says

Here’s the recipe! https://www.hadassahmagazine.org/2025/02/20/israels-ethiopian-culinary-luminaries/

Monica Sageman says

That question was for the Kulet recipe. Thank you autocorrect!

Barbara Rappaport says

What is Kyler flour. Thank you