Arts

Queen Esther Goes Dutch: An Exhibition

With the Eighty Years’ War still flaring and the yoke of Spanish rule hanging around their necks, the 17th-century Dutch were in need of a potent symbol of liberation that would speak to their fight for freedom.

Enter the biblical Queen Esther.

Rembrandt van Rijn, the great Dutch master, and his artist contemporaries found inspiration in the hero of the Purim story at a time when waves of Jewish immigrants were arriving in Amsterdam from the Iberian Peninsula. Beautiful, crafty and courageous, having saved the Jewish people from a genocide in ancient Persia, Esther seemed to resonate with the Dutch as they fought off Catholic Spain for independence.

Her story of daring wafted through the cultural air in Amsterdam and became a stand-in for the country’s political predicament. Meanwhile, the exotic setting of the biblical tale in far-off Persia (modern-day Iran) was particularly enticing as the Netherlands was fast becoming a global shipping power.

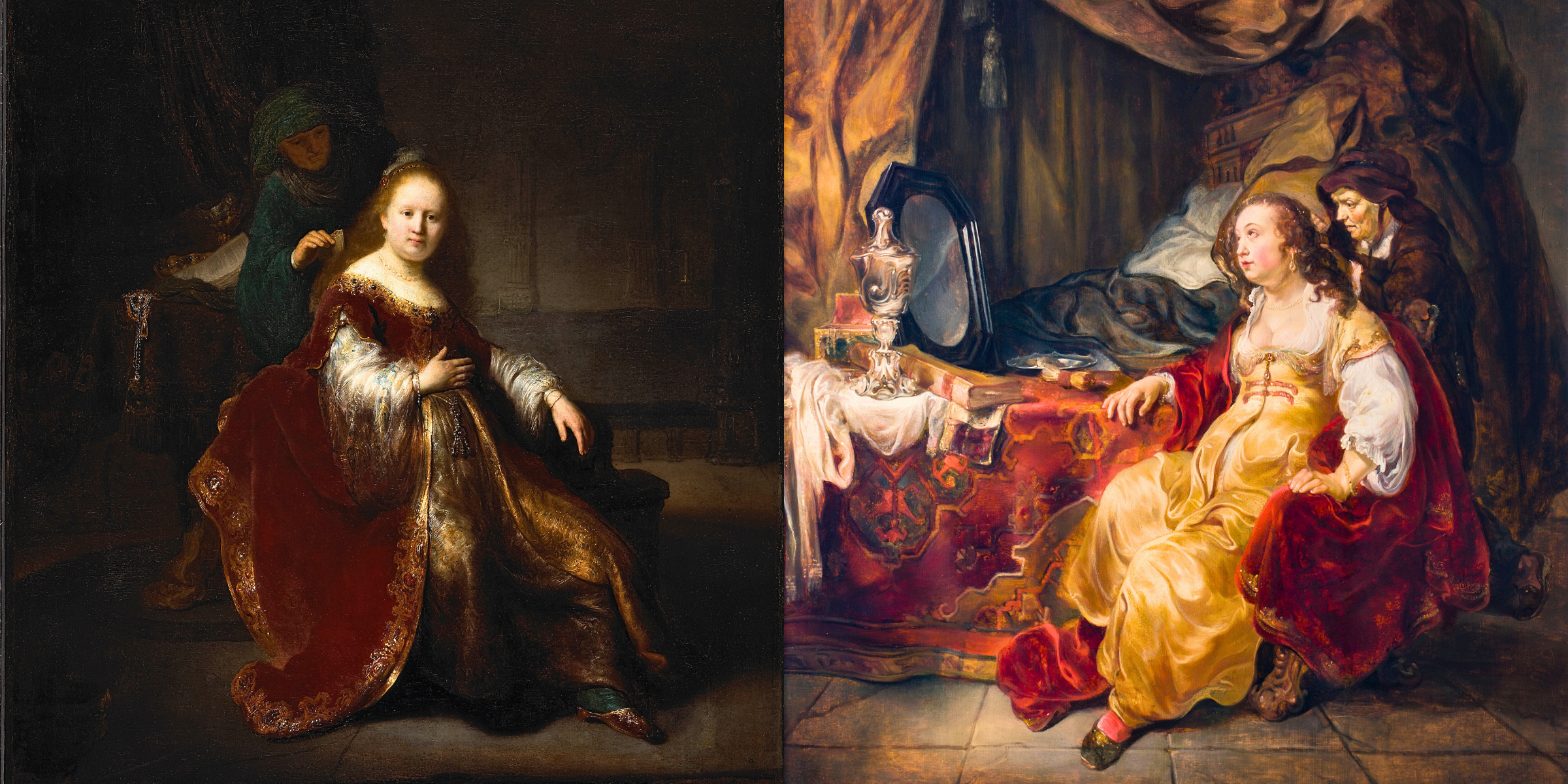

The story of Esther’s hold over the Dutch people, and their most celebrated painter, as their religiously tolerant nation was emerging is told in “The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt,” a traveling exhibition that opens on March 7 and runs through August 10 at The Jewish Museum in Manhattan. The exhibition, which curator Abigail Rapoport described as a “dialogue” between Amsterdam’s Sephardi Jews and the wider Protestant Dutch society, includes paintings by Rembrandt, his contemporary Jan Steen and his pupil Aert de Gelder. It also features ceremonial art, such as rare Esther scrolls and decorative objects.

“The Dutch at the time were kind of living with Esther,” Rapoport said in an interview. “The country was trying to get free from Spain, and she must have provided some kind of model. Amsterdam was framed as the New Jerusalem, a symbol of God’s favor for the Netherlands’ hard-fought independence.”

Indeed, Esther’s tale is one of “tyranny and triumph,” as University of Pennsylvania art historian Larry Silver writes in the introduction to the coffee table book of the same name that accompanies the exhibition.

In Amsterdam, Queen Esther, it seemed, was everywhere. Inside the Jewish community, the elaborate Esther scrolls created by Jewish illustrator and copper engraver Salom Italia—one of which is displayed in the exhibition—were wildly popular, Rapoport said. They were adorned with large-scale illustrations with figures from the Esther story set amid Dutch cityscapes, one example of the show’s cross-cultural “dialogue.”

Beyond the Jewish community, plays dramatizing the biblical tale were plentiful. Some Dutch homes featured large wooden cupboards with scenes from the Esther story intricately carved into them; those scenes also appeared etched into the cast-iron plates inside fireplaces. Snuffbox covers carried her image. Prominent Protestant women sat for portraits dressed in queenly garb—Esthers for a new generation.

Examples of the cupboards and cast-iron plates are among the more than 120 objects in the show, as are hanging Sabbath lamps bearing Esther’s likeness, a German stoneware jug with scenes from Esther’s life carved into it and a number of theater playbills for performances of the Purim story.

Rembrandt lends his sumptuous colors and magical interplay of light and dark to the subject of Esther—three of his oil paintings and five of his etchings are in the show—but he frames her in a new light.

“The essence of the show is about how Queen Esther is this icon,” Rapoport said, yet “Rembrandt is fashioning Queen Esther in his time. He’s transforming her image. Queen Esther was imagined before Rembrandt, but now he’s depicting her as a woman of their contemporary world instead of the static image of previous generations.”

In the show’s opening work, “The Great Jewish Bride (Esther?),” an etching from 1635, Rembrandt portrays a woman with a look of deep resolve, her long tresses falling over a billowy dress. She is gripping the chair she is seated in with her right hand and holding a scroll (perhaps, a Megillat Esther scroll?) in the left.

“It’s like the fate of the Jewish people is in her hands,” Rapoport said. Rembrandt, she explained, “is getting you to really focus on Esther in a lifelike way; he’s making her an empowered woman in the real world.”

James Snyder, The Jewish Museum’s director, noted in an interview that “Rembrandt had this fascination with the Jewish culture of the Netherlands, and many of his models and subjects were Jewish. And so there was total logic for his embrace of Esther at that time. But this also resonates with the social and political maturing of the newly empowered Netherlands.

“So, to look at that when we are in such a transitional social and political moment here is pretty moving,” added Snyder, evoking the current day.

The exhibition lands at a particularly fraught moment for Jews everywhere, as the antisemitism and anti-Zionism already on the rise prior to October 7 has since shot up dramatically worldwide, including in modern-day Amsterdam, when in November, Israelis soccer fans visiting the city for a game were harassed and attacked.

The Persian queen’s example provides both solace and strength for communities under siege at “such a time as this,” as Mordechai, Esther’s uncle, tells her in the Purim story.

During the 2024 election cycle, she also struck a deep chord with both sides of the political aisle in the United States. Christian conservatives seeking to mobilize women for Donald Trump saw a reflection of Esther’s bravery in their own fight, for example, against abortion rights, according to an article in The New York Times. And, in a CNN town hall, Kamala Harris mentioned that after President Biden announced that he wouldn’t run for re-election, she had spoken to her pastor about the Esther story, saying that “it was very comforting to me.”

Esther’s story, Rapoport said, is “perfect for this moment, because she’s like your quintessential heroine.… It really is a range of people, communities and cultures elevating Queen Esther.”

A similar cross-cultural “dialogue” is on display in the exhibit, with one of Salom Italia’s Purim scrolls situated next to Rembrandt’s Jewish bride, the brave queen pictured in old world Amsterdam still flexing her muscle for contemporary museumgoers in New Amsterdam.

Robert Goldblum is a writer living in New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply