Books

Feature

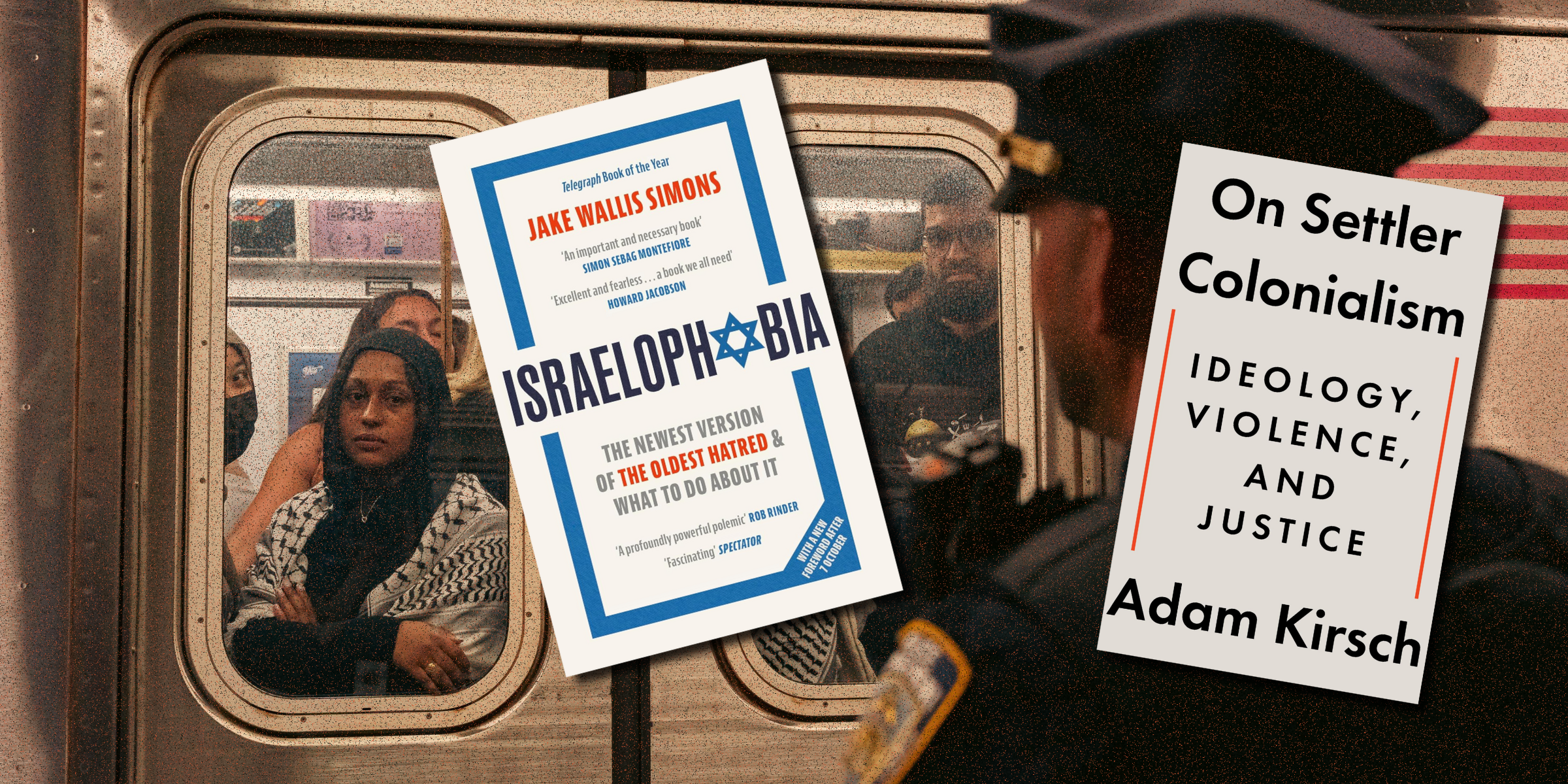

New Books Unravel Anti-Zionism

“Raise your hand if you’re a Zionist,” bellowed a man whose face was almost entirely covered by a mask on a packed New York City subway car as it pulled into the 14th Street-Union Square station. A menacing group, almost all hiding beneath masks and interspersed among crowded passengers, repeated the chant, as if under some demonic spell. “O.K., no Zionists,” the apparent leader continued. “We’re good.”

I grew up in Queens and had the good fortune to attend school with kids born in, or whose parents were from, countries such as Ecuador, Pakistan, China, the Philippines and Nigeria. I was never excluded because I was a Jew, never asked by classmates about anything related to Israel. And riding the subway is practically a New Yorker’s birthright (though I once had my wallet picked from my pocket). Of all the incidents of Jews being targeted over the past decade, and especially since October 7, none got me shaking my head in disbelief quite like this story, reported widely last June.

Something fundamental has shifted in America and around the world. It’s less comfortable and safe for Jews—and certainly any Jew who affirms Israel’s right to exist.

How did it get this bad? Why do people hate Israel? How can they accuse Jews of supporting genocide and colonialism? Is anti-Zionism automatically antisemitism, and does it matter? What happened to the world we thought we knew and what can we possibly do about it?

Even prior to October 7, explaining antisemitism had, sadly, become something of a book subgenre, with notable works including Deborah E. Lipstadt’s Antisemitism Here and Now, Bari Weiss’s How to Fight Antisemitism and Dara Horn’s provocatively titled wake-up call, People Love Dead Jews.

Add to this mix a slew of new works, including On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice (W.W. Norton) by Adam Kirsch, literary editor of the Wall Street Journal, and Israelophobia: The Newest Version of the Old Hatred and What to Do About It (Constable) by Jake Wallis Simons, editor of The Jewish Chronicle.

What these two books have in common is a focus on irrational hatred of Israel and its role in antisemitism’s resurgence. Though the white nationalist far right is mentioned and correctly identified as a menace, both set their sights on the progressive left, with very different results.

Kirsch, formerly of The New Republic, has written with erudition and clarity on a range of subjects, including the Talmud and the future of artificial intelligence. With On Settler Colonialism, Kirsch has given us a work we didn’t know we needed, making a compelling case that understanding the ideology of settler colonialism is key to unpacking the antipathy toward Israel and Jews. In a little more than 150 pages, he guides the reader through a college course’s worth of material on African postcolonial history, Australian politics and American campus culture.

As Kirsch explains, settler colonialism started out in the 1960s as a somewhat obscure academic theory to help predict the fate of newly independent nations around the world. Yet over time it has become less an academic theory to explain the past and more a political ideology. Colonialism wasn’t just something tragic that happened in the past, resulting in the eradication of countless native peoples, it is ongoing, argues the theory. In this view, America and Australia remain settler colonial states and all non-native peoples are settler colonialists to this day.

“What is distinctive about the ideology of settler colonialism is that it proposes a new syllogism: If settlement is a genocidal invasion and invasion is an ongoing structure, not a completed event, then everything (and perhaps everyone) that sustains a settler colonial society today is also genocidal,” Kirsch writes.

As Kirsch describes it, the true aim of those who subscribe to the settler colonialism ideology is the unattainable goal of dismantling long-established countries like the United States and Australia and returning those lands to native peoples. While banishing hundreds of millions of non-indigenous Americans might be science fiction, evicting eight million Jewish Israelis from the Holy Land seems much more feasible.

Kirsch makes a clear and convincing argument that Israel, faults and all, is neither a colonial nor genocidal nation.

Among his arguments against the accusation of colonialism is rather than expanding to fill a continent and displacing the native population, as in North America, the Jewish immigrants remained within a relatively small geographic area. “The language, culture, and religion of the Arab peoples remain overwhelmingly dominant in the region,” he writes.

Indeed, for Israel to fit the world-view of settler colonialist ideology, the definitions of colonialism and genocide have to be altered, he explains. Thus, Israel can be accused of committing both.

Those who might dismiss this as the argument of a right-leaning ideologue might be surprised to encounter an impassioned and compelling plea for a two-state solution. Perfect justice, Kirsch writes, would allow both Israelis and Palestinians full control of the land. Since that’s impossible, the two-state solution represents imperfect justice. “The tragedy of Israel-Palestine is that it is harder to imagine the humane futures than the cruel ones,” he writes.

The book manages to stay on track because it adheres to a narrow focus—explaining the harm caused by a particular worldview. The reader won’t find much on how current settler colonialist philosophy connects to traditional antisemitism or critical race theory—which has been an obsessive focus of the right. And what to do about it, other than think more clearly. This isn’t the book for mapping out a strategy.

As convincing as his argument is, I still have trouble with the idea that every expression of de-colonialism is inherently pernicious. We’ve seen examples of writers, artists, even chefs taking inspiration from the concept of de-colonialism. For example, chef and author Sean Sherman, who grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, has turned his restaurant Owamni into a Minneapolis hot spot, making dishes without any ingredients introduced to North America by Europeans, including dairy, sugar cane and black pepper.

Kirsch also finds Native American land acknowledgement—public statements recognizing that an event or institution might be transpiring or sit on land once inhabited by indigenous people who once lived in an area—troubling. He writes that, at best, they are disingenuous and, at worst, a mock call for the destruction of the United States. But there must be some way different groups can negotiate this terrain from a place of understanding, as opposed to a zero-sum game.

Israelophobia is a very different book, more explicitly partisan in tone, less aimed to convince than fortify. Simmons’s central thesis is nothing we haven’t read before but remains important to restate: Israel is uniquely demonized among all nations; such demonization is rooted, consciously or unconsciously, in antisemitism; and Jews in the Diaspora are targeted as a result. He sets out to prove this by piling on example after example.

There’s certainly value in reading the details of incidents that many in the United States might not have known before, especially in Simmons’s native Britain. Simmons offers the most detailed account I’ve read about Soviet propaganda efforts to discredit Israel and Zionism, which began in the 1940s and continued through the 1990s, and how much the former Soviet Union’s talking points are used today by opponents of Israel.

Here’s how Simons describes his title, no doubt a riff on Islamophobia: “Israelophobia is a form of antisemitism that fixates on the Jewish state, rather than the Jewish race or religion. It cloaks old bigoted tropes in the new language of anti-racism and presents hatred as virtue. It rests on propaganda that was invented by the Nazis and Soviets; and as a political rather than racial phenomenon, it can more easily recruit small numbers of like-minded Jews.”

The Oxford dictionary defines phobia as “an extreme or irrational fear of or aversion to something.”

Does this match what Simons describes? An aversion, maybe, but a fear? Simons spends little time explaining Israelophobia, a term that seems more designed to stoke outrage than clarify reality.

Readers looking for an alternative term would be better served reading Jonathan Karp’s “Anti-Israelism” essay in the winter 2024 issue of the Jewish Review of Books. Karp writes that anti-Israelism “is a sweeping judgment of an entire people, country, state, and culture that we would not tolerate if it were directed at anyone else.”

“What to do about it” is right in Simons’s title, and here is where the book falls short. Instead of focusing on strengthening Jewish identity, building alliances with other groups or behind-the-scenes political advocacy, he offers rhetorical comebacks to criticisms of Israel in verbal conversations or online encounters.

At the end of reading both books, I found myself torn between wanting to consult more books in search of solutions and feeling like fighting hatred is such an uphill climb I might as well read about more uplifting subjects.

When I first explored Israel and Zionism in my early 20s, I didn’t see myself as retreating from my multicultural New York experience. Rather, perhaps naively, I thought that with a stronger connection to the world’s lone Jewish state, I’d have a deeper identity to share with my neighbors of other backgrounds. Today, that feels like a distant, impossible dream, as renouncing Zionism is now the only possible ticket into many cultural spaces.

Yet, as Theodor Herzl, someone with more than a passing connection to Zionism, once said, “If you will it, it is no dream.”

Bryan Schwartzman is a writer living outside Philadelphia.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply