Arts

‘June Zero’: Three Tales Around Eichmann

Jake Paltrow’s latest film, June Zero, has an unlikely but fascinating origin story. The idea, said the director, “grew out of [my] learning the fact that only Mizrahi officers were allowed to guard Eichmann and the unusual detail that in a culture and religion with no cremation, an official decision was made to incinerate Eichmann’s body after he was hanged.

“Both seemed like very compelling places to start from,” he added.

The result is indeed a compelling anthology of three distinct yet interconnected short films related to the captivity, trial and death of the infamous Eichmann. Each film focuses on a different character: David Saada (played by Noam Ovadia), a precocious 13-year-old Jewish Libyan immigrant to Israel; Haim Gouri (Yoav Levi), the Jewish Moroccan prison guard charged with guarding Eichmann; and Micha Aaronson (Tom Hagi), a Polish-born Auschwitz survivor and an investigator for the prosecution.

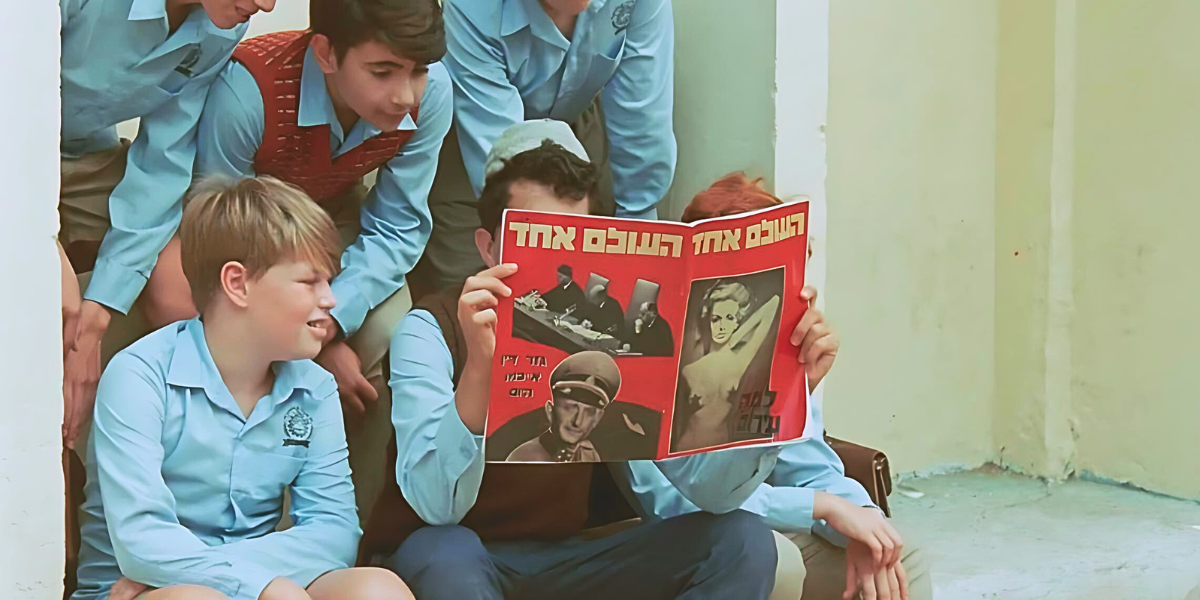

We meet David first, running with his younger brother from a merchant after shoplifting goods. David doesn’t fit into his new country; he is picked on by fellow students because he’s slight and by his teacher because he’s Sephardi and an immigrant.

When he’s kicked out of school, his father lands him a temporary job at a factory that manufactures bakery ovens. He’s hired principally because he’s small enough to enter and clean tiny compartments in the factory. David proves himself a bright and capable employee and impresses his gruff new boss, Shlomi Zebco (Tzahi Grad), referred to as Zebco in the film. The job gives David both a sense of purpose and a feeling of inclusion.

Paltrow then switches focus to Haim, who is charged with assuring Eichmann’s safety—until he is hanged, the first capital punishment in Israel’s history. The country is full of Holocaust survivors and those with family members who didn’t survive, so Haim is specifically tasked to ensure no European Jews are allowed near the prisoner, which is why only Mizrahim guard him.

Haim becomes obsessed and overprotective of his charge. A barber sent to cut the prisoner’s hair is constantly restrained by Haim as he moves his scissors. In response, the barber tells the guard: “You Israeli police have it all wrong. You’re his prisoner.”

The Israeli government decides to cremate Eichmann after he is executed and then scatter his ashes at sea to prevent his burial site from becoming a Nazi shrine. (The title of the film comes from the official date of execution, listed as June Zero to decrease the possibility of anniversary commemorations.)

The problem is that, with cremation forbidden in Judaism, not only are there no crematoria in Israel, no one even knows how to build one. Haim, who knows Zebco, turns to him for assistance. He even offers Zebco plans used by the Nazis to build theirs, an offer that Zebco angrily turns down. Instead, David will prove instrumental to the project.

The third story features Micha, the investigator gathering evidence against Eichmann. The movie follows him to his native Poland, where he is a featured speaker on a Jewish Agency trip, during which he shares his experiences under the Nazis—from being whipped by a Nazi soldier to surviving Auschwitz. But the pain followed him to his new land.

“My own people’s disbelief was the first blow,” he tells a tour group in Poland. His immigration officer did not believe the stories he told about his treatment at Nazi hands.

It’s an emotional speech that affects the group. And when the attractive tour leader knocks on his hotel room door, my first thought was, this smart film is going to descend into rom-com territory. Just the opposite. She wants him to lead tour groups to the camps and the ghettos. But Micha bristles, angry that they want to turn the sites of these atrocities into a tourist attraction. “They’re not sanctifying the memory,” he says to her. “They’re just commemorating the crime.” And no, he tells her, he doesn’t want to return to Auschwitz. “I’ve already been to Auschwitz,” he says.

Individually, each film in the anthology is entertaining and thoughtful. Viewed together, they touch on issues that resonate in the Jewish state today: The treatment of Sephardi and Mizrahi immigrants and questions about how to remember the past without commercializing it, or being consumed by it.

The three don’t always fit together perfectly in tone and content, but that is a minor distraction. What is noticeable, however, is how expertly the film is cast. This is young Ovadia’s first film, and he is a natural in the role of David.

Indeed, all the main characters inhabit their roles, apparent in tiny moments, such as the panic on Haim’s face when he suspects his prisoner has died before his execution. He rushes into Eichmann’s cell and holds a mirror to his face to check for breathing.

The script, co-written by Paltrow and Israeli writer Tom Shoval, is also excellent—a perfect blend of fact and fiction.

For example, the role of Haim “is a composite of a number of different officers,” Paltrow said. “The oven factory really existed in Petah Tikva and the crematorium was built there. And they really sent one of the factory workers to Ramle Prison the night of the execution to operate it.”

But through the research process, the director explained, “We filled in the details and invented characters.”

Another of Paltrow’s choices was to mostly shoot the film in Israel. “It ultimately seemed essential to largely make the movie in the location and language”—the film is in Hebrew, with English subtitles—“where the events really took place,” he said.

The 48-year-old Paltrow is the son of Jewish director and producer Bruce Paltrow (The White Shadow and St. Elsewhere, among others) and the Tony- and Emmy-award winning actress Blythe Danner. He is also the younger brother of actor Gwyneth Paltrow.

Preceding my next question, I offered a disclaimer that it might be stupid—then asked him if he thinks often of his father, who died at age 58 more than two decades ago.

“It is not a stupid question at all. I’d go one step further to say that the meaning of my Judaism and my Jewishness is my father, and in turn his connection to his father and my grandfather’s connection to his father and so on. Philip Roth and David Simon articulated this view of Judaism so beautifully in the adaption of The Plot Against America.

“I think my father would be proud of this movie,” he continued. “I talk to him in my head all the time and at every stage of the process…. We disagree a lot.”

June Zero is now playing in select theaters.

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply