Books

Finding True Love at a Nazi Concentration Camp

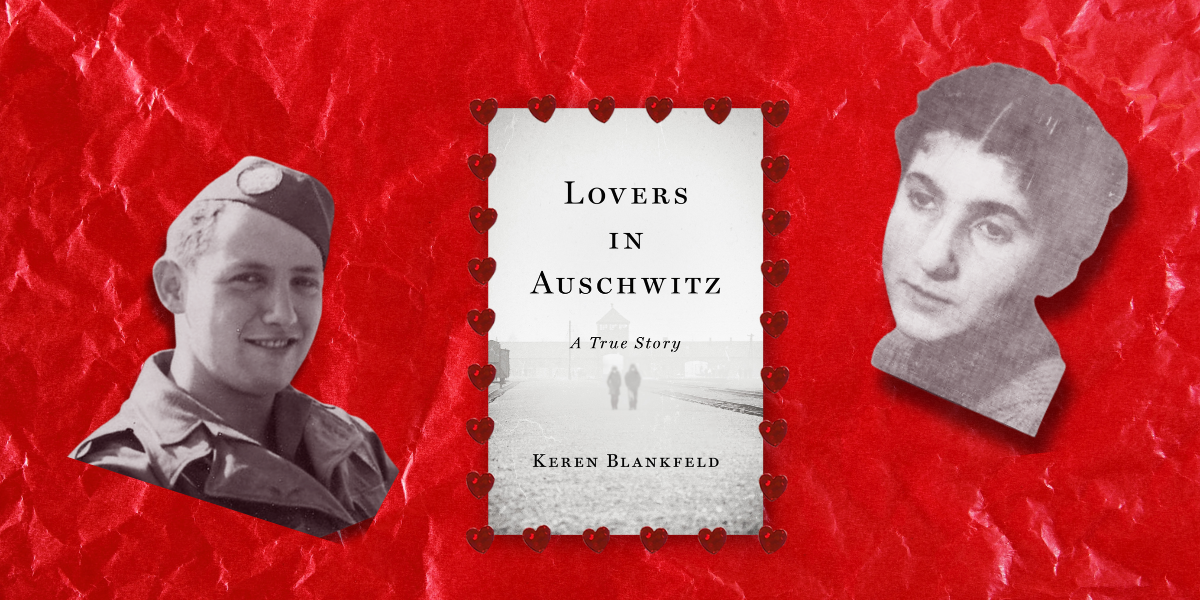

Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story

By Keren Blankfeld (Little, Brown and Company)

Can true love be forged in a Nazi concentration camp? Sex, probably, but abiding love? Journalist Keren Blankfeld’s Lovers in Auschwitz, an account of an unlikely love story, provides a strong and poignant answer eight decades after the Holocaust.

Helen “Zippi” Spitzer was a 25-year-old graphic designer when she was sent to Auschwitz. Determined to survive, she took on clerical duties, designed diagrams of the camp for officials and cleaned Nazi uniforms, all of which gave her relative freedom.

Another inmate, David Wisnia, 17, a child singing star in Warsaw, was also privileged. His captors had discovered his vocal talents and called upon him to entertain the guards, in addition to other duties such as laundry work.

Spitzer had noticed Wisnia at the “Sauna,” where clothing was cleaned and disinfected, and decided to approach him. “She chose me,” Wisnia said in an interview with Blankfeld near the end of his life about his relationship with Spitzer.

And so they became romantically involved, meeting at the barracks between crematoria 4 and 5. There, in a space they constructed from piles of prisoners’ clothing, they consummated their relationship, guarded by fellow prisoners who had been bribed with additional food rations.

Blankfeld poignantly describes their once-a-month trysts. In brief conversations during their “dates,” Wisnia told Spitzer of his father, an opera lover killed in the Warsaw Ghetto, who had inspired him to sing. Spitzer, who played the piano and mandolin—she had been in an orchestra in Bratislava—taught her young lover a Hungarian song, “Evening in the Moonlight.”

The secret meetings continued for months, and, at one point, the couple made plans to reunite in Warsaw if they were separated after the war.

But their lives went in different directions. Wisnia escaped captivity and was rescued by American soldiers. From Auschwitz, Spitzer was sent to several other camps before escaping during a death march.

Amid the chaos of postwar Europe, Spitzer made it to Feldafing displaced persons camp in the American zone of occupied Germany. Wisnia found a job with the American military and delivered supplies to Feldafing. Yet the former lovers’ paths never crossed.

At one point, Spitzer traveled to Warsaw and waited for Wisnia to no avail.

Blankfeld first came across their story when interviewing Wisnia in 2018 for an article on World War II refugees. For her book, she supplemented that account with an unpublished memoir by Spitzer as well as interviews with historians and recorded accounts of her story. Lovers at Auschwitz ably places the couple’s story into historical context, beginning with the Nazis’ rise to power in the 1930s and deftly continuing through to Wisnia and Spitzer’s final years.

In September 1945, Spitzer married Erwin Tichauer, the Feldafing camp’s acting police chief. She and her husband, a trained bioengineer and university professor, then moved to Australia and, eventually, to the United States, ending up in New York City, where he taught bioengineering at New York University.

For his part, Wisnia arrived in the United States not long after the war and, in short order, married and started a family. Based in Levittown, Pa., he became vice president of sales for an encyclopedia company and served as a cantor at his congregation for many years.

In the mid-1960s, he learned that the woman he had loved in Auschwitz was living in New York City. A mutual friend arranged a get-together and Wisnia drove the two hours to Manhattan for a meeting in a hotel lobby across from Central Park. She never showed up.

“I found out after,” Wisnia told Blankfeld, “that she decided it wouldn’t be smart. She was married; she had a husband.”

Wisnia kept tabs on her through their mutual friends and, in 2016, reached out again and she agreed to a reunion. Her husband had died in 1996, and she was ill and homebound. The reunion was in her apartment.

At first, she did not recognize her long-lost love. Then something clicked and they began talking in English. After reminding him that she had saved his life five times, she added: “I was waiting for you.” She had loved him, she told him quietly. He had loved her, too, he said. And then he sang the Hungarian song of their youth.

They never saw each other again. She died in 2018 at age 100. He died three years later at 94. Their reunion occurred 72 years after they first met.

Theirs is a love story like no other. It is a privilege to share and honor it.

Stewart Kampel was a longtime editor at The New York Times.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply