The Jewish Traveler

In Portugal, Shadows of a Jewish Past

The Portuguese town of Castelo de Vide, less than 20 miles from the border with Spain, is as picturesque as they come. Its enchanting cobblestoned streets redolent of Jewish ancestry and wreathed in the scent of linden trees beg to be photographed. Its whitewashed homes adorned with glazed azulejo ceramic tiles dazzle the eyes. Yet hewn into the exterior stone walls of some of those houses are symbols left over from a dark page of history: the Portuguese Inquisition, which lasted almost 300 years.

The Portuguese town of Castelo de Vide, less than 20 miles from the border with Spain, is as picturesque as they come. Its enchanting cobblestoned streets redolent of Jewish ancestry and wreathed in the scent of linden trees beg to be photographed. Its whitewashed homes adorned with glazed azulejo ceramic tiles dazzle the eyes. Yet hewn into the exterior stone walls of some of those houses are symbols left over from a dark page of history: the Portuguese Inquisition, which lasted almost 300 years.

Above one doorway on Rua Nova (New Street), a crude carving of a fish representing St. Peter, the catcher of lost souls, floats above a name etched into the stone: Maroc. This once was the home of a formerly Jewish family that chose baptism to escape the Inquisition’s wrath. They were moved from the adjacent Jewish quarter to Rua Nova, a street that took its name from these residents who were New Christians, a term used in Portugal for conversos, or Jews who converted.

There are Rua Novas all over Portugal. The contrast between the country’s sunny charm and the Inquisition’s ruthless legacy gripped my heart and my imagination on a group tour I experienced earlier this year that was organized by the Jewish Heritage Alliance (JHA), a global nonprofit dedicated to preserving and promoting the legacy of Sepharad—the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula. The inquisitions in Spain and, later, Portugal were watershed events in Jewish history, yet they “receive scant attention,” said JHA founder and CEO Michael Steinberger.

Portugal’s breathtaking vistas stretch from north to south, from the stunning Douro Valley wine region to the southern Algarve coast. They include its two main cities—Porto in the north (also called Oporto) and Lisbon in the center of the country—along with smaller mountain towns.

Nobody really knows when Jews arrived in Portugal, said Rabbi Peter Tarlow, the tour’s academic leader and co-founder of the Center for Latino-Jewish Relations and Crypto-Jewish Studies. The earliest archeological evidence of Jewish life dates to the third century.

The Spanish Inquisition established in 1478 by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella intensified following the Edict of Expulsion in 1492 that forced Jews and Muslims to convert to Catholicism or leave. About 100,000 Jews fled west, to Portugal, whose Jewish population at the time was significantly smaller.

Their safety was short-lived. As a condition for marrying the infanta Isabella of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, Portugal’s King Manuel I promised to convert or expel his country’s Jews. In 1496, he promulgated an Edict of Expulsion, however, due to the prominence and professional influence of the Jews, the king didn’t want them to actually leave, and he instituted a 20-year grace period in which they were not investigated. Nevertheless, thousands of Jews left, fleeing to North Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

The Portuguese Inquisition was established by King João III in 1536 and targeted New Christians and crypto-Jews, the latter a subset of New Christians who maintained secret Jewish practices. Some 50,000 crypto-Jews left Portugal. Others hid in Portugal’s small towns. According to scholars’ estimates based on the available documentation, more than 1,100 were burned alive in autos-da-fé—public sentencings followed by punishment—and close to 30,000 suffered imprisonment and torture.

In the 19th century, a small number of Jews returned to Portugal, mainly from Morocco and Gibraltar. Some Eastern European Jews fleeing pogroms and economic ravage in the 1920s passed through on their way to other countries; a few stayed. Approximately 380 Jews were living in Portugal at the outbreak of World War II and an additional 650 Jewish refugees from Central Europe were granted resident status.

Today, Portugal, which has become a hot tourist destination, has a Jewish population of about 6,000. Most are French or Israelis whose Portuguese heritage traces back through ancestors who sought refuge in the former Ottoman Empire and North Africa. Studies estimate that the number of Portuguese with some Jewish lineage is as high as 40 percent out of a total population of more than 10 million. Worldwide, JHA estimates that there are 200 million people who are descended from either Spanish or Portuguese Jews.

Since 2015, descendants of Jews who were expelled have been able to obtain Portuguese citizenship. About 100,000 have applied and half have received citizenship; several thousand have moved to Portugal.

Portugal’s Jewish saga unfolded for me in layers. In Castelo de Vide, former mayor Carolino Tapadejo, a descendant of crypto-Jews, detailed the city’s Jewish history from Roman times to 1320, when 49 families from Gibraltar settled there. Thirteen years later, they received permission from the king to build a synagogue. Following the Spanish expulsion, 4,000 Jews crossed the border near Castelo de Vide. Among them were Tapadejo’s ancestors from Toledo.

Born on Rua Nova, Tapadejo, as a boy, often visited a neighbor who lit a hidden candle on Friday afternoons. “She told me, ‘This is what my grandmother did,’ ” he recalled. “She told me, ‘This is also your family [heritage].’ ”

“I am not religious,” said Tapadejo, whose wife is also of crypto-Jewish descent, “but like most b’nei anousim [descendants of forced converts], my heart is Jewish, and my children and grandson feel the same.”

After he was elected mayor in 1974 at the age of 26, Tapadejo organized the municipality’s purchase of the synagogue on Rua da Judiaria and helped turn it into a small Jewish museum.

Another museum, the House of the Inquisition, graphically depicts every aspect of the inquisitorial process. All the life-size wax figures—of guards, judges and victims—are modeled after the likenesses of real people now living in Castelo de Vide. Tapadejo posed for our group alongside a figure of the inquisitorial judge modeled after him, his smiling face a contrast to the judge’s grim expression. Also on view is a replica of a wooden cupboard that secretly housed a small Ark with a Torah.

Porto, almost 200 miles northwest of Castelo de Vide, is a vibrant, bustling mecca of tourists and residents along the Douro River. Its Jewish community has also spearheaded a number of museums.

A reconstruction of an Inquisition prison carriage greets visitors to the Jewish Museum of Porto, which opened in 2019. The museum retells Jewish history stretching back even before Portugal became a kingdom in 1143. For generations, Jewish merchants had their offices along the Douro, which flows through the city and extends 550 miles from Spain to the Atlantic.

For me, the most dramatic lesson of the museum came from learning about heroes such as Captain Artur Carlos de Barros Basto. Born near Porto in Amarante, Barros Basto, a descendent of crypto-Jews, officially converted back to Judaism in 1920. He founded the modern Porto Jewish community 100 years ago, when he was the sole Sephardi among a group of 30 Ashkenazim. From 1927 to 1930, he scouted rural towns in search of crypto-Jews, seeking to reintegrate them into communal life. He supervised the building of the Kadoorie-Mekor Haim Synagogue with donations from the Sephardi diaspora, including a hefty gift from the Baghdadi Kadoorie family.

That synagogue, located across the street from the museum, is the largest on the Iberian Peninsula. It was inaugurated in 1938, when synagogues in Nazi Germany were being razed. Its gleaming white Art Deco exterior and majestic Ark of maroon, navy and gold reflect Barros Basto’s ambitious goal of reviving the community. Today, the congregation boasts a membership of 1,000.

But Barros Basto’s work among the crypto-Jews failed for many reasons, including their refusal to convert to Judaism or give up rituals antithetical to Jewish law. Over the centuries, as families kept secret Jewish practices without any further education, their faith became diluted. In Portugal, that specific crypto-Jewish faith is called marranism, without the derogatory nuance that that word carries in Spain.

Like Alfred Dreyfus, his contemporary in France, Barros Basto experienced personal disgrace motivated by antisemitism. He was falsely accused of sexual misconduct before being dishonorably discharged from the army in 1937 for having taken part in the circumcisions—not illegal but considered immoral within the military—of several men with Jewish heritage. The uniform he was deprived of wearing is on display at the museum.

Portugal’s little-known role in the Holocaust is delineated in Porto’s Museum of the Holocaust, which has welcomed more than 100,000 students—10 percent of the country’s schoolchildren—from all over the country in the two years since it opened. A long wall displays 412 identification cards issued by the Portuguese Committee for Assistance to Jewish Refugees. Some of these Jews had received life-saving visas signed by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul general in Bordeaux, France, who issued thousands of visas to Jews in defiance of his government.

In Lisbon, 200 miles south of Porto, two synagogues played a major role in Holocaust rescue. Shaare Tikvah, established by Sephardi Jews from Morocco and Gibraltar, and Ohel Jacob, founded by Polish Jews in 1943, served as sanctuaries for thousands of Jewish refugees during World War II, providing food, clothing and health care. Some of the refugees stayed and changed the complexion of the community.

Shaare Tikvah, completed in 1904 and designed by well-known architect Miguel Ventura Terra, was the first synagogue built in Portugal since the Inquisition. Ohel Jacob is a Reform congregation that has welcomed crypto-Jews interested in returning to Judaism.

Lisbon holds special interest for the Chabad Lubavitch movement because the city was the point of departure for the Lubavitcher Rebbe—the late Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson—when he fled Europe in 1941 aboard the Serpa Pinto, headed to New York. The Rohr Chabad Portugal-Avner Cohen Casa Chabad in the nearby suburb of Caiscais welcomes visitors and residents alike. Its library contains a collection of rare books dating to the 15th century, including a copy of the first book ever printed in Lisbon, a commentary on the Torah by Moses ben Nahman, who is also known as the Ramban or Nahmanides.

Lisbon’s two ancient Jewish quarters, centered in the Alfama and today’s Praça do Comércio districts, were destroyed by an earthquake in 1755. The nearby Praça do Rossio, the city’s liveliest area, was the site of the Court of the Inquisition, where Jews and other heretics were burned at the stake.

At the edge of the square, outside the São Domingos church, is the site of the Jewish Lisbon Memorial. The simple round stone marker embedded with a silver Magen David memorializes the victims of a 1506 massacre, during which approximately 4,000 New Christians were murdered after they were accused of causing the plague and drought that were sweeping the country.

It was easy for me to imagine Portugal’s medieval past in its interior towns, some of them walled or formerly walled cities situated in the dramatic landscape of the Serra da Estrela Mountains. In Coimbra, Portugal’s capital from 1139 to 1260, I could picture Jewish merchants gathering in the main square until the Inquisition made the city its regional headquarters.

The University of Coimbra is the oldest university in Portugal and one of the oldest in Europe. Its students wear black cloaks that are said to have inspired the robes worn by Hogwarts’ students in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. As our tour entered the university’s ornately tiled and painted St. Michael’s Chapel, I noticed the nametag on a young chapel employee, Catia Cardoso. I asked her about her last name, which was one commonly adopted by Jews during forced conversions. She looked puzzled but told me that cardo means thistle, so she believes that she comes from a place where thistles grow.

She didn’t mention, and may not even know, that Isaac Cardoso was a prominent 17th-century physician, philosopher and scholar born in Portugal to a crypto-Jewish family. In fact, at our next stop, in the town of Trancoso, we visited the Isaac Cardoso Interpretation Centre of Jewish Culture, opened in 2012 by the local government.

Less than an hour’s drive south of Trancoso, the isolated hill town of Belmonte seems an unlikely place to find any Jews, past or present. But the area’s Jewish roots stretch back centuries. Today, the community of 45 maintains an active Orthodox congregation led by an Israeli rabbi. Souvenir shops sell Judaica as well as locally produced kosher wine.

A seven-branched menorah set against a red door unmistakably announces Belmonte’s Beit Eliahu Synagogue, built in 1996. The words of the Shema run the length of the sanctuary on a wall supporting the women’s balcony. The unique ner tamid is designed from an open pot with a spouted neck, a larger replica of what was used to hide and light Shabbat candles at home. Several group conversion ceremonies took place in Belmonte until the mid-1990s, when most of its Jews immigrated to Israel, Spain or the United States.

Our guide at Beit Eliahu was 15-year-old Rafael Diogo, the son of the community’s president. Through a translation provided by tour leader Peter Tarlow, Diogo recounted the community’s history. Belmonte’s Jews, he explained, were forced to convert in 1496. However, they maintained their identity for over 400 years by largely marrying among themselves; lighting candles surreptitiously on Friday night; and observing holidays a day or two before or after the proper date on the Jewish calendar to confuse the Inquisition.

The community survived thanks to the unusual charity of their Christian neighbors, who didn’t denounce them. Because of Belmonte’s remote hilltop location, the town’s Jews believed they were the only ones in the world until 1917, when they met Samuel Schwarz, a Polish-born engineer who was running a mining operation in the area. In the course of his work, Schwarz found medieval Hebrew inscriptions on a stone in Belmonte that he believed belonged to a 12th-century synagogue.

At first, some of the locals denied they were Jewish, but when they heard Schwarz recite the Shema, they told him the truth. Schwarz documented their social and religious customs, prayers and manuscripts. The enigmatic stone is housed in Belmonte’s Jewish museum, which also displays Inquisition-era artifacts.

I thought about the Belmonte congregation, a testament to abiding Jewish faith, back in Lisbon during my visit to Shaare Tikvah. I asked Sandra Montez, who conducted our tour of the synagogue, about her own family background. “Sorry to disappoint you,” she said. “I’m not Jewish.”

Later, however, she revealed that during her tourism studies, she felt something was missing from her courses: research about the Jewish community. She began studying Judaism on her own and learned Hebrew. “Whenever my mother would cook, and the knives would cross, the first thing she would do was uncross them,” she told me. “But if you would meet them [my parents], they were absolutely Catholics. Something didn’t fit very well. When I realized that, they were already older and could not explain why and how. A lot of what we had was lost in the past 500 years.”

The official governmental website features numerous descriptions of Jewish sights. Several tour operators offer Jewish heritage trips through Portugal, including, among others, the Jewish Heritage Alliance, Robyn Helzner Jewish Heritage Tours, Gil Travel and the TripAdvisor-backed Viatour, which also offers day tours of Jewish sights in Lisbon and Porto.

Porto

Visit Porto’s six landmark bridges, including the 1877 Maria Pia Bridge, a symbol of Portugal attributed to Gustave Eiffel, and the Dom Luis de Porto bridge, which you can cross by foot.

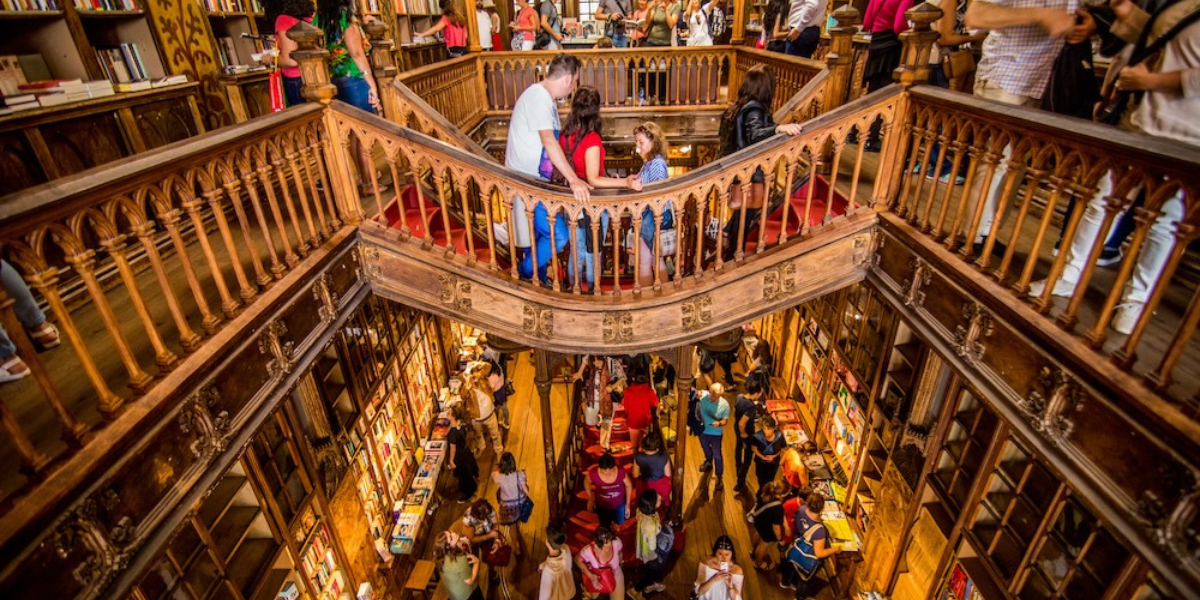

Not far from the riverfront, the famed bookstore Livraria Lello, built in 1906 with a neo-Gothic exterior and Art Deco interior, is rumored to have inspired J.K. Rowling’s depiction of Hogwarts’ sweeping staircase as well as the Flourish and Blotts bookshop in Diagon Alley, though the author herself has denied this.

A plaque marks the site of the main synagogue that once stood on the Escadas da Vitória. Another plaque in the former Judiaria do Olival commemorates the expulsion and honors the Jews who kept their faith. Other worthwhile Jewish sights include the Jewish Museum of Porto and the Museum of the Holocaust. The Kadoorie-Mekor Haim Synagogue has two rabbis, one Sephardi and one Ashkenazi, who alternate leading services, which are Orthodox.

The Crowne Plaza is within walking distance of the synagogue, as is the Hotel da Música, which features a kosher restaurant open to the public. Book in advance for that restaurant as well as the city’s only other kosher eatery, Iberia.

Trancoso

Casa do Gato Preto, the House of the Black Cat, said to have been the rabbi’s residence in medieval times, is decorated with a Lion of Judah and depiction of a Jerusalem gate with an inscription, “Made by Lopo, 1530.” Today, it is a private residence.

The Isaac Cardoso Interpretation Centre of Jewish Culture tells the stories of some of the town’s illustrious Jewish families, including how they fared during the Inquisition, and maps the spread of their descendants worldwide. The museum also houses a small synagogue, Beit Mayim Hayim.

Belmonte

Explore Belmonte’s fascinating Jewish history—past and pre-sent—at the Beit Eliahu Synagogue and the Jewish Museum of Belmonte.

Castelo de Vide

Castelo de Vide’s Jewish sights include a Jewish museum on the site of a 14th century synagogue (Rua da Judiaria) and the House of the Inquisition. Yet another museum is scheduled to open soon, a tribute to native son Garcia de Orta (1501 to 1568), a crypto-Jewish physician, herbalist and botanist who escaped with his family to Goa, India.

Coimbra

The University of Coimbra’s Biblioteca Joanina, completed in 1728, is a darkly spectacular library built in the Baroque style and ornamented with gold from Brazil. One of the rarest possessions among its 60,000 volumes is the 15th-century Abravanel Hebrew Bible, a handwritten, richly illustrated manuscript commissioned by a Sephardi family that fled to Amsterdam and the Balkans during the Inquisition. The library also owns the largest collection of Portuguese Inquisition verdicts outside of Lisbon.

A long-term exhibition, “The Jews from Coimbra: From Tolerance to Persecution,” is on view in the city’s former Inquisition headquarters.

Lisbon

Lisbon’s spacious and sheltered natural harbor at the intersection of the Tagus River and the Atlantic Ocean served as a point of embarkation and return for Portuguese explorers and is marked by the 16th-century Belém Tower, now a UNESCO monument. The Monument to the Discoveries honors Prince Henry the Navigator, who led Portugal’s search for a route to Asia by sailing south around Africa.

Shaare Tikvah is a 900-member Orthodox Sephardi congregation with daily services. Many hotels are within walking distance, including the Dom Pedro. Ohel Jacob offers Reform services. Rohr Chabad Portugal-Avner Cohen Casa Chabad in Caiscais is among the largest Chabad centers in Europe and offers meals and daily services to travelers and residents.

Portrait of a Hero: Aristides de Sousa Mendes

In 1940, thousands of refugees amassed outside the Portuguese consulate in Bordeaux, France, requesting visas to Portugal to escape Nazism. Portugal, officially neutral yet unofficially pro-Hitler and under the dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, forbade its diplomats to provide safe haven.

One man defied the order. Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul general in Bordeaux, issued thousands of visas in May and June of 1940 before Salazar stripped him of his position. “I would rather stand with God against man than with man against God,” Sousa Mendes declared at the time. Salazar forbade him from earning a living and blacklisted his 15 children. The bank repossessed the family’s ancestral home, Casa do Passal, which was eventually sold to pay off debts. Sousa Mendes died in poverty and disgrace in Lisbon in 1954. Now regarded as the Portuguese Oskar Schindler, Sousa Mendes’ story is relatively unknown. In 1966, he was posthumously recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

Decades after his death, former Portuguese President Mario Soares apologized to the family, and the nation’s parliament promoted Sousa Mendes to the rank of ambassador and offered reparations to his descendants. The Sousa Mendes Foundation, founded in 2010 and based in New York, has worked with the municipality of Carregal do Sal, where Casa do Passal is located, to fund the home’s reopening as a museum, scheduled for July 19, 2024, Sousa Mendes’s birthday.

For Jeannette (Cookie) Fischer, Sousa Mendes’ heroic act is personal. Her mother, Dutch-born Adele Margaretha van den Bergh, escaped on June 22, 1940, on the sardine schooner Melina with a Sousa Mendes visa.

“If it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t be here,” said Fischer, who recently moved to Lisbon from California and is the foundation’s liaison for the Jewish and American communities in Portugal.

In July, she co-led the fifth “Journey on the Road to Freedom” tour, which traces the work of Sousa Mendes and the path the refugees took from Bordeaux to Lisbon.

Fischer’s mother, who passed away in 1994, kept her story a secret from her daughter. Her passport and visa, which were discovered among her papers in 2016, are currently on display at Casa Chabad in Cascais. “It is emotionally powerful to revisit the places where my mother spent time during her escape,” Fischer said. “It has helped me to understand her peril and uncertainty, her emotions and fears, and, through it all, her courage.”

Rahel Musleah leads virtual tours of Jewish India and other cultural events. To learn more, visit Explore Jewish India. In June, her Jewish heritage tour through Portugal was sponsored by the Jewish Heritage Alliance.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Valerie Knowles says

Thank you for this wonderful article

My grandmother was a certified genealogist and she traced my ancestors back to Portugal into 1400s and 2018 I did a 23 and me and guess where I was before Portugal ?

Spain. This explains why I’m so interested in Sfardi things. I want to be able to go to Portugal and find all these wonderful Jewish places and the history, and I have been to Spain, but only in Barcelona.

natascha Joling says

Catharina Antonia Josephina Verbist born December 26, 1916 in The Hague, Netherlands

In connection with my family tree research, I would like to know where in which country and at what age she died.

To this day, rumors circulate in our Family that Catharina Verbist married Emile Smulders on March 28, 1942 to avoid deportation to Germany, the marriage was dissolved on August 21, 1945.

On 01.09.1956 Catharina Verbist married Dennis L.B Upjohn, in an advertisement in the newspaper they indicated their future address Rue Dante Tanger Maroc (Morocco).

According to a newspaper advertisement, they both lived in Lisbon in 1964, after which nothing more can be found about them

The name Upjohn is known worldwide as a pharmaceutical company, unfortunately nothing can be found about him on the internet?

Can you help me, while waiting for a positive message, kind regards Natascha Joling