Israeli Scene

Books

Israeli Female Writers Are Having a Moment

Novelist Ayelet Gundar-Goshen remembers when she was in her late teens and her mother, a teacher with a serious library, brought home a book by Israeli author Maya Arad. Her mother put it “on the shelf with the Israeli male authors,” Gundar-Goshen recalled. For the acclaimed novelist, “it was a moment.”

Israeli female writers these past few years have also been having a moment, a significant one. According to the National Library of Israel, 2022 was the second consecutive year that the majority of new novels and books of poetry published in the country were authored by women.

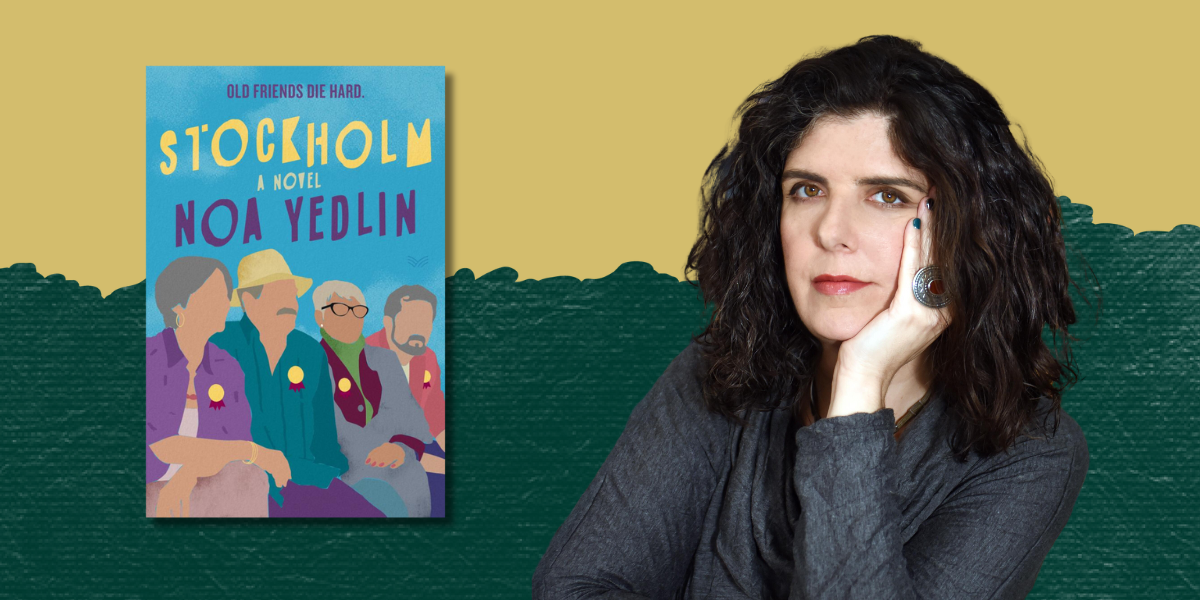

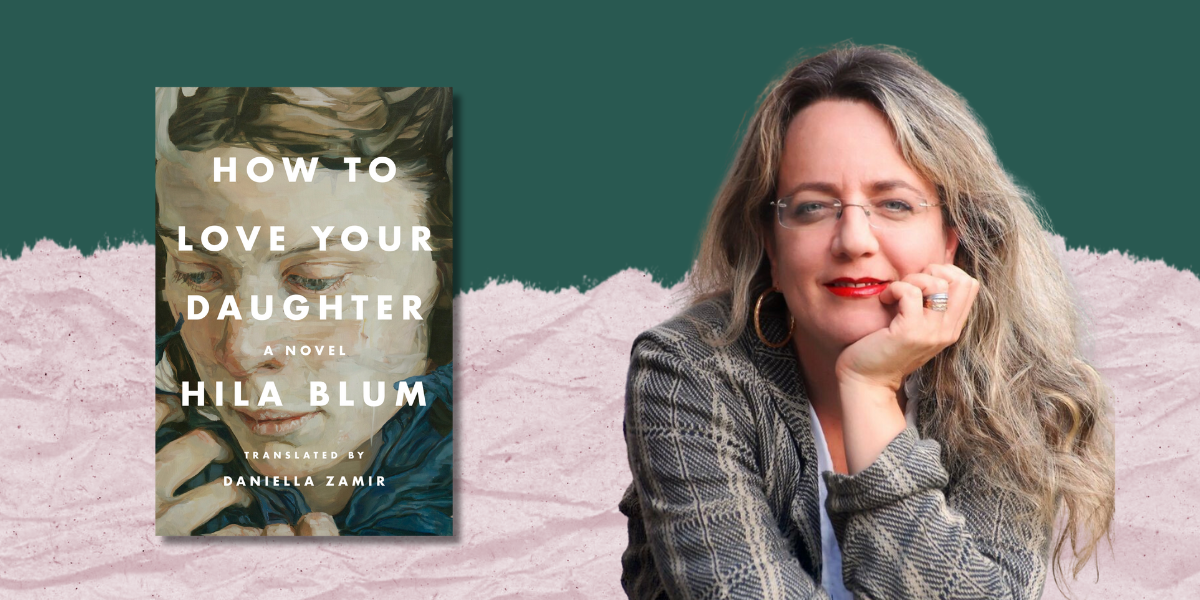

Gundar-Goshen, whose most recent book to be translated into English is The Wolf Hunt, is among this latest generation of skilled storytellers. Also included in this cohort are Hila Blum, whose novel, How to Love Your Daughter, won the 2021 Sapir Prize, Israel’s top literary award; Maayan Eitan, author of the debut novella, Love; Dana Shem-Ur and her debut, Where I Am; and veteran novelist Noa Yedlin, whose most recent work is Stockholm. These women, all in their 30s through 50s, are residents of Tel Aviv, except for Blum, who lives in Jerusalem. Their books have been published recently in English.

If David Grossman and the late writers A.B. Yehoshua and Amos Oz have been the leading lights of Hebrew literature of the past, these women are the sparkling present. Much like their extraordinary male predecessors, they are interested in investigating the details of both surface life and deep interior truths. All address big questions about modern society through the lens of fiction, such as the dissonance and displacement faced by emigrants (Where I Am), or dig into relationships, whether between mother and child (The Wolf Hunt and How to Love Your Daughter) or a group of friends (Stockholm). Contemporary in approach, they are both of Israel and global.

As Blum noted of her novel, “Its thematic emphases are, of course, not exclusive to Israel, but it is Israeli. Everything in it is relatable to me.”

If the focus of each of these five books is diverse—parenthood and aging; the complexities of identity and love; how people are ultimately unknowable—there is one thing they all share: a gnawing unease. Many of the characters experience an underlying anxiety, and all the novels end with a lingering sense of ambiguity for readers to ponder.

Perhaps that’s an indicator of the mood in Israel—even before the current crisis engulfing the country—or the world, or a not-uncommon literary shrug today.

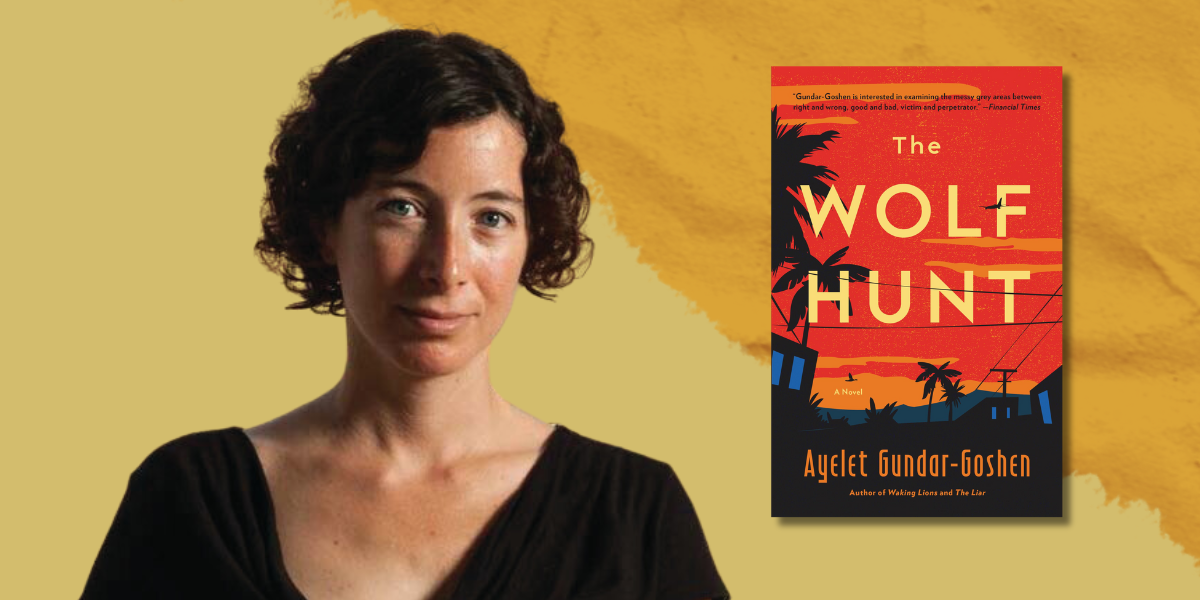

Ayelet Gundar-Goshen is, arguably, the best known of these authors in the United States, with three of her earlier books translated into English. The Wolf Hunt (Little, Brown), translated by Sondra Silverston, is set in Silicon Valley and features at its center an Israeli couple and their son. An attack on a local synagogue distresses their ex-pat community, leading parents to enroll their kids in a self-defense course taught by a former Israeli military officer. Soon after, a young Black boy in the community dies at a party of an apparent drug overdose. Lilach, the Israeli mother—called Leela by Americans who can’t pronounce her name—wonders whether her son, Adam, might have had something to do with the boy’s death.

The novel is full of psychological depth, suspense and nuanced understanding of the conflicting identities of Israelis living abroad. The book investigates this conflict through the languages—Hebrew and English—that the characters use in different settings; their connection to family back in their native country; and their attraction and bemusement with American life. “When our son was born, we gave him a neutral name—Adam—that would work in both Hebrew and English,” Lilach recalls. “A name that would slide down the throats of the Americans like good California wine….”

A 2013 Sapir winner for her debut novel, One Night, Markovitch, Gundar-Goshen is a practicing clinical psychologist and has worked as a journalist and screenwriter. She explained that she was inspired to write The Wolf Hunt while dropping off her daughter at a preschool in Tel Aviv. She realized all the mothers were looking suspiciously at the other children, wondering if any would bully their child. Central to her novel is the question of how well a mother can really know her kid, how well anyone can know another person.

“It’s interesting how we are all afraid of ‘the wolf,’ not considering the possibility that our own child may be the wolf,” she said. “We don’t stop to acknowledge that we all have the ability to do evil.”

Asked about the importance of a sense of place in fiction, Gundar-Goshen, who lived in San Francisco in 2018 while a visiting scholar at San Francisco State University, said her focus is on “the DNA of the human soul” and not on a specific geographical place. “On the other hand,” she noted, “I love when the story is well-settled, when you can feel the soil.”

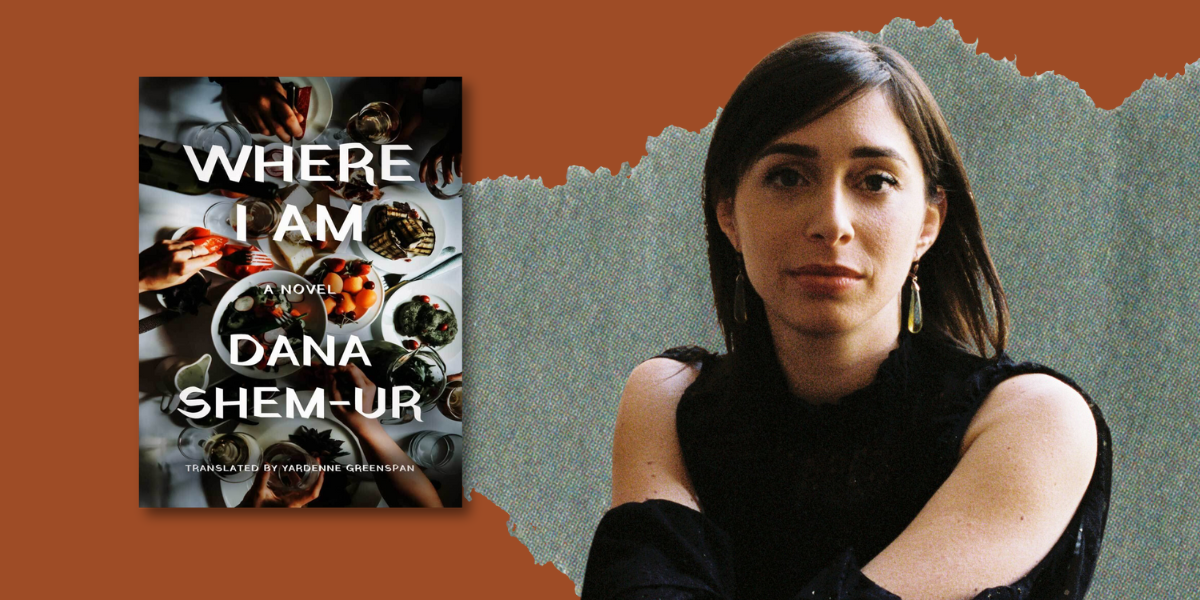

Readers can certainly “feel the soil” in Dana Shem-Ur’s Where I Am (New Vessel Press), translated by Yardenne Greenspan. It, too, is set outside of Israel, and is lush with the sights, sounds, food and the cultural minutiae of France. Reut, an Israeli literary translator, is living in Paris with her French philosopher husband, Jean-Claude, and their child, Julien. In the midst of deadlines, Reut agrees to a lavish dinner party and then a trip to Italy with a group of her husband’s affluent, intellectual friends. This leads to revelations about her own dissatisfaction with the life choices that forced her into the roles of mother and wife. The events also reveal her disconnection from the city she now calls home and her nostalgia for her native country and, as Shem-Ur writes, “that Israeli spontaneity, that tendency to force strangers into becoming friends.”

Shem-Ur depicts Reut’s alienation along with moments of delight, like the pleasure of a conversation with a stranger on an airplane. Where I Am excels at capturing the subtleties of language and the possibility of passion and intimacy as well as the textures of time, light and travel. In one example, the book describes the Adriatic Sea as resembling “a slender bottle of wine” with its rock formations “flanking the turquoise water from both sides, almost meeting in the middle.”

Shem-Ur began writing the book in Paris while earning her master’s degree in philosophy. “You can’t avoid what you know. This novel is set in Paris,” she said. “But it’s about an Israeli.”

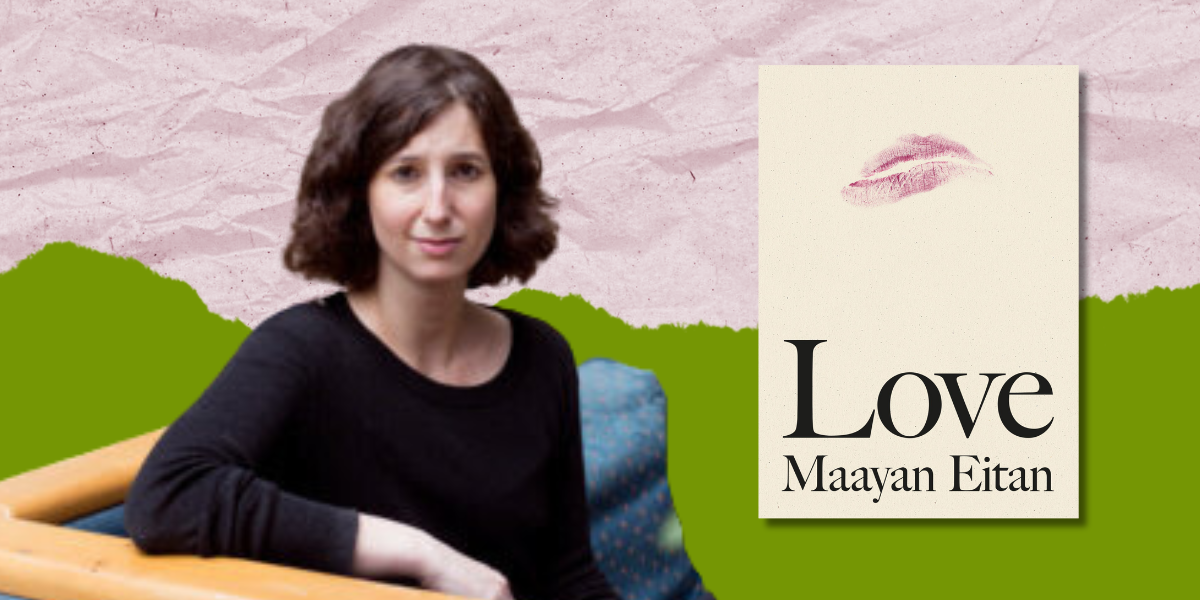

In contrast, Tel Aviv is unmistakably the setting for Maayan Eitan’s first book of fiction, Love (Penguin Press), even though the Israeli city where Libby, the protagonist, works is unnamed.

The novella, a sensation in Israel, was the winner of the 2022 National Jewish Book Award’s inaugural Jane Weitzman prize for Hebrew Fiction in Translation.

Love is a finely chiseled and disquieting portrait of Libby (her name a transliteration of the Hebrew Libi, which means my heart), a young woman earning her living though prostitution. In short vignettes and rapid, first-person narration, Libby describes her evenings encountering clients in homes and hotel rooms arranged by her pimp. She recalls her childhood as she shares gum and alcohol in the back of cars with fellow prostitutes, including an Ethiopian woman working her way through college. She also reflects on masculine desire, the omnipresent male gaze. “I fell asleep with their arms around my waist, but my sleep was erratic, brief, and eventually I slipped from under their bodies, put on my clothes again, and got out of there,” Libby recounts.

Eitan, who translated her own book into English, weaves in references to literary works such as the poetry of Sylvia Plath and Paul Celan. She injects the text with a raw musicality even as she describes Libby’s emotional detachment and cold indifference to the sex act. Libby, throughout, remains a mystery, yet one the reader comes to care about.

Although Noa Yedlin’s novel Stockholm (HarperCollins), translated by Jessica Cohen, is named for a Swedish city, it is also set in Tel Aviv. A great portraitist, Yedlin writes about a group of five Israelis who have been close since their army days 50 years earlier. One of them, a noted economist, is rumored to be a Nobel Prize finalist. When he dies suddenly just before the prize is to be announ-ced, the others decide to “postpone” his death, that is, not alert anyone, until after the Nobel announcement. A dark and very funny comedy of errors, and manners, the novel is a multilayered exploration of friendship.

Each chapter goes deeply into one character, revealing back stories, loyalties and secrets. Yedlin’s characters are people in their 70s, inhabiting that window before advanced old age when, she said, “there’s still time to make changes, still time to correct what you have done wrong. But you don’t have all the time in the world.” The novel was made into an award-winning television series in Israel.

Yedlin, the recipient of the Sapir Prize for her 2014 novel House Arrest and, in 2021, the Prime Minister’s Prize for Hebrew Literary Works, notes the common, everyday focus of her novels. “I think good novels have a universal core,” she said. “They touch the innermost places in the human soul, be it Israeli, Chinese or North American. People are people all over the world, made of the same feelings.”

That universality of emotion, mapped onto a mother-daughter relationship, shapes Hila Blum’s How to Love Your Daughter (Riverhead), translated by Daniella Zamir. An editor of literary fiction, Blum examines the fractured relationship between an Israeli mother, Yoella, and her only daughter, Leah. “The core of our existence, wherever we are, is practiced through relationships, mother-daughter among the most crucial,” Blum said.

A work of emotional archaeology, the novel opens with Yoella peering into a window in a foreign city. She is watching the granddaughters she has never met, children of her own beloved daughter who has disappeared from her life. Yoella then shifts through time to look closely at their lives in Israel—the dance lessons, school nights, trips to Europe—asking how deep maternal love can lead to estrangement.

The novel’s clear, piercing prose is compelling, disturbing and memorable. “I’d studied her face hundreds of times, thousands, always thinking, you take my breath away,” Yoella muses while gazing at her daughter.

Blum said she knew the sentiment she wanted to convey in the novel before she knew the story or characters. “What if,” she said, “with all the good intentions in a tender, caring and loving relationship, you might stand and look backward and realize that something has gone very wrong.”

Blum, the author of the 2011 Israeli best seller The Visit, is making her English-language debut with How to Love Your Daughter. And she doesn’t shy away from the label “Israeli female writer.”

“I am all those things,” she said. Yet, she quipped, “if you give me some more options, those might resonate, too.”

When asked about the prominence of female writers in contemporary Israel, Eitan answered, “There’s more space and a feeling that those voices have more room to be heard.”

“It’s a generational change,” Gundar-Goshen said. “Women can write novels that will tell the great Israeli stories as much as men. It’s a very important shift.”

For her part, Yedlin acknowledges the importance of male writers to the Israeli canon in the past but pointed out the lack of significant female representation. “The canon was hermetically closed,” she said. “Whenever a newspaper wanted to hear an opinion on current events, when there was a need for someone to speak at a rally, it was always the same male writers. When you thought of an Israeli writer, you thought of them. In recent years, this has changed. For many reasons. The world changes. The structure of the literary market changes.”

There are many other prominent female authors whose voices could have been included along with these five. Several of these authors mentioned Maya Arad—the novelist whose book Gundar-Goshen can so clearly recall on her mother’s bookshelf—as an influence and a friend. Literary critics sometimes refer to her as the best living writer of her generation. She’s the author of several highly praised novels in Hebrew; her work will be available in English for the first time in March 2024, with the publication of The Hebrew Teacher.

Israel is small enough that these authors said that most female writers know each other, or at least their work, and are generous to one another. “It’s not necessarily a community,” Gundar-Goshen said, “but a fabric made of words.”

Sandee Brawarsky is a longtime columnist in the Jewish book world as well as an award-winning journalist, editor and author of several books, most recently 212 Views of Central Park: Experiencing New York City’s Jewel From Every Angle.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply