Arts

Exhibit

Chagall’s Dark Period: Exhibit Review

and Paul Amir, Bevery Hills, CA,

copyright Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York/ADAGP, Paris.

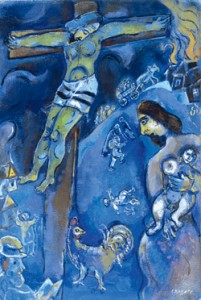

Although Marc Chagall is best known for his whimsical folk motifs and fanciful color paintings, his work during the war years of 1930 to 1948 attest to a different artistic reality, having a grim and emotional intensity. “Chagall: Love, War and Exile,” a new exhibit at The Jewish Museum of New York, through February 2, 2014, covers this dark period and reflects the drama of that era. The exhibit focuses on persecution and suffering, in particular the artist’s Crucifixion scenes, which, though somber, still contain Chagall’s iconic imagery and imaginative style.

Solitude, for example, seems like a typical Chagall painting—but with a different veneer. The background depicts a surreal landscape of colorful houses and spires amid a light blue sky where an angel flies away, but there’s a cloud of blackness surrounding the figures: A solitary bearded fellow in a talit holding a red Torah scroll sits on a green hill, turned away from the violin-playing cow who can offer no consolation. The year is 1933, and Chagall knows that Fascism is spreading across Europe. The plaintive melancholy of the forlorn figure attests to the helplessness and rage Chagall feels.

These feelings escalate and, by 1941, shortly after his arrival in the United States, Chagall painted Persecution, which shows Jesus in a talit loincloth with his head bent and feet hanging off the crucifix. It is still rendered in the lush blues of Chagall’s more joyous paintings, with a rooster, a scholar and a mother with child at the foot of the cross—but in the background the shtetl is burning.

By 1944, with The Crucified, Chagall has moved to drab grays to depict the shtetl, but this time Jews are on the crosses, people are dying in the empty streets, and the bearded man on the roof is not a fiddler, but holding a crimson Torah, against the dark, black sky.

In this exhibit, Chagall’s poetry (he wrote poetry from 1909 to 1910, influenced by Russian symbolism) is prominently displayed on placards high above his paintings.

“Should I paint the earth, the sky, my heart?

The cities burning, my brothers fleeing?

My eyes in tears. Where should I run and fly, to whom?”

Clearly the artist—who was born in Belorussia in 1887 and died in his adopted France at age 97 in 1985—was torn about sitting out the war in America (while still in France, his friends had advised him to leave). In April of 1941, while awaiting passage out of France, Chagall was arrested. It was Varian Fry, director of the Emergency Rescue Committee in France, who secured his release. Chagall and his wife, Bella, arrived in New York in June of that year, greeted by Pierre Matisse.

Throughout the war, Chagall had many showings at Matisse’s New York gallery, but even though his career went well, he could not ignore the suffering of the world he had left behind. Further tragedy struck as the Chagalls planned their return to Europe in 1944, after D-Day and Paris’s liberation: Bella died suddenly of a viral infection.

Over the next few years, some of his paintings lightened up, such as Cow with Parasol, with the blue-headed bovine sporting a bride and groom from its tail (Chagall had a new wife by then). And slowly, after he and his family returned to France, his work regained its former joie de vivre.

Some have critiqued this exhibit for ending on a high note, with the last of the four rooms called “The Colors of Love,” but how apt it is: It represents the soul of the Jewish people, decimated and ravaged, who rise from the ashes once again.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Paula Ste. Marie says

Concise and interesting review.. thank you