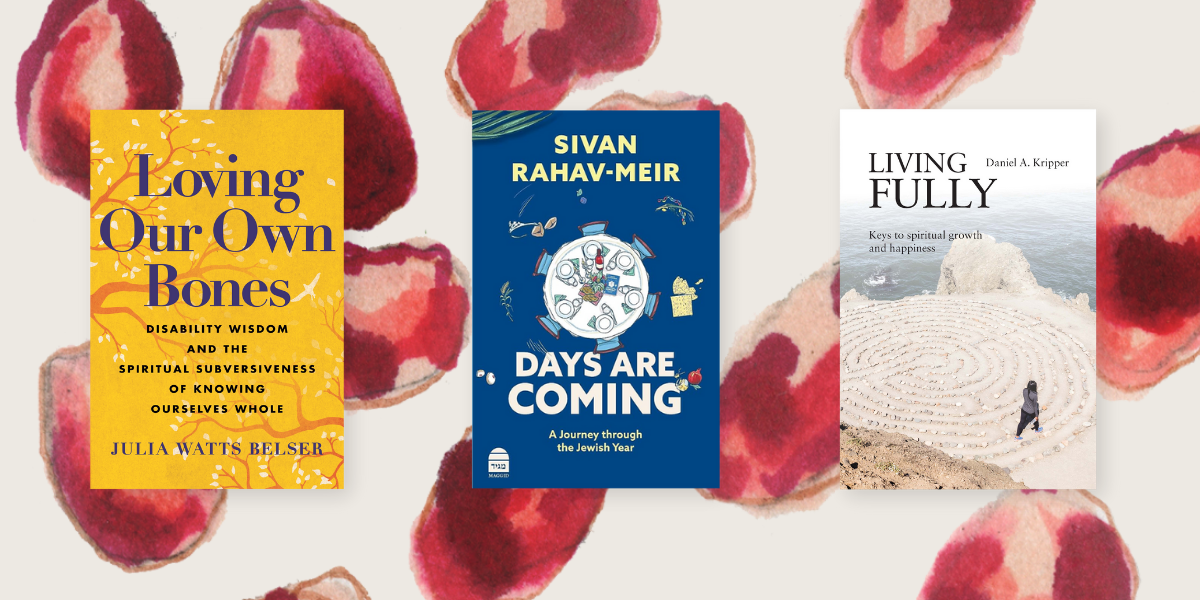

Books

Inspiring Books for High Holiday Reading

Living Fully: Keys to Spiritual Growth and Happiness

By Daniel A. Kripper. Translated by Nadia Hlebowitch (Hadassah New Orleans)

Kripper, an educator, life coach and rabbi at Temple Shalom, a Conservative congregation in Middletown, R.I., shares insights into what he calls the “wide-ranging moments in life, whether happy occasions or moments of crisis or regret.” In nine chapters that delve into different themes, including gratefulness, mastering fear of change and happiness, the Buenos Aires-born rabbi weaves together anecdotes and thought-provoking quotes. The result is a cornucopia of scholarly musings on each theme from both Jews and non-Jews, with every chapter concluding with practical tips, activities, questions and visualizations for further exploration.

Yom Kippur and its leitmotifs of apology and repentance are naturally highlighted in the section on forgiveness. Both accepting and offering apologies for wrongdoings are necessary to beginning the New Year “free from the burden of negative feelings,” Kripper writes. Through quotes from Maimonides, Rabbi Yosef Cairo and the Kabbalah, he describes traditional Jewish injunctions and understandings around repentance and apologies. He also explores the limits of forgiveness, asking readers how, and if, they would forgive a terrorist or those who attempted genocide.

Forgiveness, the rabbi notes, is “a virtue that all religions have emphasized, each in its own way, highlighting its benefits both emotional and spiritual.” Our task, he writes, is to practice forgiveness—and indeed all the attributes explored in Living Fully—each day, using contemporary thought and “drawing on the wisdom of ancient texts.”

Originally published in Spanish, the English translation and paperback publication of Living Fully was a project of Hadassah New Orleans.

Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole

By Julia Watts Belser (Beacon)

In the second chapter of her new book, Belser, a rabbi, disability activist and Jewish scholar, describes an anecdote she once read: A teacher in a religious school promised a Deaf child that “One day, in the world to come, you’ll be able to hear.” The child looked at the teacher and replied, “No. In the world to come, God will sign.”

Taken from an essay by Rabbi Margaret Moers Wenig, a senior lecturer at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the story speaks to the heart of Loving Our Own Bones. The book asks for the complete reframing of disability from a source of shame that must be hidden to a marker of identity to be explored.

According to Belser, a professor of Jewish studies in the theology department at Georgetown University, religious communities have “tended to treat disability as a problem to be solved, rather than a perspective to be embraced.” Utilizing personal anecdotes as well as scholarly examination of Jewish (and some Christian) texts and traditions, she persuasively argues that discussing disability can offer insights into the “textures and tenor of spiritual life.”

After all, Belser notes, disability is everywhere in the Torah. Moshe stutters. Isaac becomes blind. Jacob’s wrestling with an angel leaves him lame. In separate chapters, she discusses these examples and others, describing how each has impacted the lives of those with disabilities, either by providing an example to follow and uphold or as a tool of erasure and marginalization.

Moses’ stutter didn’t prevent him from being a leader, yet a midrash insists that he had been “healed” through the learning of Torah before speaking to all of Israel in the desert—a perspective that Belser rejects.

“When I read the Book of Deuteronomy, I hear him speaking in my heart,” she writes. “I hear him stutter through the long, beautiful recitation of his own life’s story. I hear him stutter without flinching. I hear him stutter without shame.”

Belser, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, finds significant personal meaning in the first chapter of the biblical book of Ezekiel. She describes the sudden sense of kinship she felt several year ago when reading of Ezekiel’s vision of God as a radiant fire seated on a chariot held by four angelic creatures with fused legs and wheels, their “wheels within wheels,” according to the text, “gleamed like beryl.”

Like her, she writes, “God has wheels.” The joy, satisfaction and freedom she finds in her own wheelchair is reflected in the Torah itself.

Days Are Coming: A Journey Through the Jewish Year

By Sivan Rahav-Meir. Translated by Yehoshua Siskin (Maggid)

Using the Hebrew months as her guide, Israeli journalist and popular television and radio personality Rahav-Meir takes readers through the Jewish year.

Known for her lectures and videos on the weekly Torah portion, Rahav-Meir uses that same folksy, conversational tone to discuss Jewish and Israeli holidays, events and even yahrzeits of Jewish luminaries—from Rav Kook, in the Hebrew month of Elul, to the matriarch Rachel, commemorated in Heshvan.

“The cycle of the Jewish year is a journey, taking us through a process of growth,” she writes in her introduction. “In order to truly appreciate the gifts these holidays bring, we need to know as much as possible about them.”

The book starts with Elul, the month that precedes Rosh Hashanah and usually coincides with September. The section includes meditations on teshuvah, repentance, as well as a description of Israeli singer Naomi Shemer’s popular back-to-school children’s song “Shalom, Kita Alef” (“Hello, First Grade”). The song describes a young child leaving his or her mother to go to school: “And mother is already standing there, like Yocheved or Miriam in the reeds. The breeze is singing, ‘A great journey begins today’; shalom, first grade.”

According to Rahav-Meir, Shemer’s tune is not just about school, books, pencils or the “usual threats of teachers’ strikes” in Israel. The singer is connecting to the generations of Jewish mothers who have watched their young children venture forth to new experiences with hope and trepidation.

These moments of insight into Israeli culture are woven throughout the book, as are mentions of the broad diversity of Jews in Israel. Included are discussions of Sigd, a day celebrated in Heshvan for “fasting, purification and renewal” by the Ethiopian community, and the Moroccan Mimouna, the day after Passover during the month of Nissan. Days Are Coming describes the commemoration of Yom Hazikaron, Yom Ha’atzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim as well as Tu B’Av and International Women’s Day, all present on the Israeli calendar. Also included are lesser-known commemorations, such as the seventh of Adar, designated as the day to remember all the fallen Israel Defense Forces soldiers whose bodies were never recovered.

Each entry captures a point on the calendar, an event or a thought that resonates, touching on topics from love and gratitude to resilience and faith. Meir-Rahav, who is Orthodox, draws upon traditional Jewish sources and texts for many of her anecdotes. She also includes the voices of contemporary female scholars—Rabbanit Chana Henkin, Yael Ziegler and others—who have broken boundaries in Orthodox Jewish communities.

“I remember hosting a broadcast in the news studio,” Rahav-Meir writes, “when one of the commentators said, ‘The elections will be held between Purim and Passover so that the government will be formed by Shavuot.’ ” While electing a functioning government is clearly important, she adds with a touch of irony, for her the mention of that very Jewish time frame was illuminating. “The holidays are not just dates on the calendar. They are our common denominator—our past, present and future.”

Leah Finkelshteyn is senior editor of Hadassah Magazine.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply