Books

Feature

Documenting the Memories of Anne Frank’s Friend

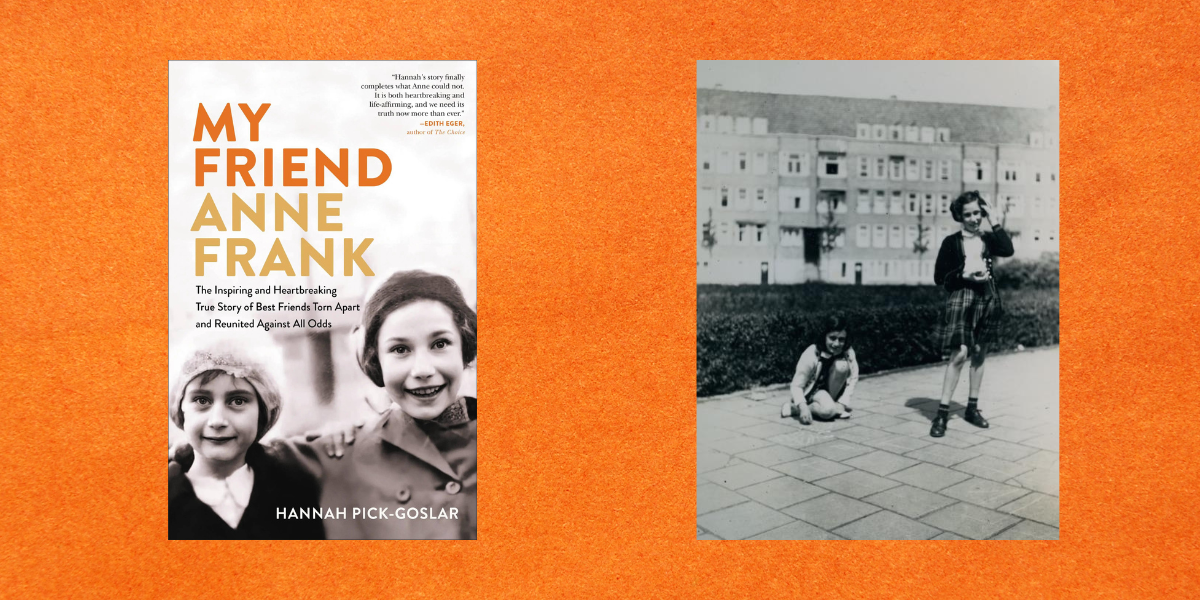

When I started working with Hannah Pick-Goslar on her memoir, published recently as My Friend Anne Frank (Little, Brown Spark), almost 90 years had passed since she first met a small-framed girl with dark shiny hair—and a lot to say—named Anne Frank.

The first time they glimpsed one another, as Hannah described it, was at a corner grocery store in the spring of 1934. Anne was 4 and Hannah, six months older, already 5. Clinging to their mother’s skirts, they exchanged shy glances, both of them newly arrived German Jewish refugees to the Netherlands who didn’t know a word of Dutch or anyone else their age. The two became neighbors and close friends, until Anne and her family went into hiding.

It was clear that the time left to collect Hannah’s recollections was short. At 93, Hannah was in delicate health, though her mind was sharp and full of gripping memories to share. We were starting our interviews in spring 2022, when Covid was still a threat. On the first day I was scheduled to interview her in her Jerusalem apartment, I woke up feeling sniffly. I took a Covid test: positive. So we began our interviews by Zoom, she sitting in the living room of her garden apartment in Jerusalem, me at my dining room table in Tel Aviv. We’d lift our cups of tea in greeting toward the screen and settle down to unpack the past.

I tried to push away my anxieties. How could we develop a rapport through the computer screen, and later, in person, through a mask and on opposite ends of a table? How would I reach the level of intimacy and immediacy I needed to help bring Hannah’s story to life? How could I help her delve more deeply into those long-ago memories, some of them the most traumatic of her life?

The memories we discussed were of her experiences as a girl growing up under Nazi occupation, then as a survivor of the horrors and degradations of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and, finally, the rebuilding of her life in Jerusalem, where she immigrated in 1947, after her parents, grandparents and close friends were murdered in the Holocaust.

Despite my fears, we quickly found our footing. I appreciated Hannah’s deep intelligence, dry wit and warmth. She soon felt like a new friend.

Hannah began sharing her experiences publicly in 1957 at the behest of Otto Frank, Anne’s father. The two had connected after the war, after he had discovered her name on a list of camp survivors and traveled eight hours to find her at a hospital in Maastricht, in the Netherlands, where Hannah was recovering from her ordeal in Bergen-Belsen.

Till her last days, she referred to him as she did when she was a girl: Mr. Frank. At that time in the 1950s, she was one of the few survivors talking about her experiences. By then, Anne’s diary, which was first published in Dutch in 1947, had become an international sensation, and its adaption into a hit Broadway play gave it even more reach.

For Hannah, sharing her story, first as a public speaker and later, in the twilight of her life, as a memoirist, was a decision to tell the story Anne had not lived to tell, that of Nazi persecution beyond the confines of the cramped attic apartment. Persecution that happened, as Hannah often said, “only because we were Jews.”

Returning to those difficult times during our interviews was not easy for Hannah. She had to confront painful memories, including the death of her mother in childbirth (the baby was stillborn) just months before the family was deported. They were forced from their home in Amsterdam—unlike the Franks, they did not go into hiding—to Westerbork, the transit camp on the damp and boggy Dutch-German border. Jews from the Netherlands were sent there, a purgatory of sorts ahead of transport “East.” No one knew exactly what awaited in the “East,” but what she and the others in the camp did know was that no one who left ever sent letters back or returned.

Sometimes when Hannah and I would sit together and I’d prod her for yet another detail or scene, she’d shrug and ask, “Who is going to find this interesting?”

Sadly, she did not live to learn the answer. She died last October, a few weeks shy of her 94th birthday, while I was still writing. But the story she left behind is now being read around the world, written up in newspapers, spoken about on podcasts and even making The New York Times best-seller list.

The Anne Frank story has long coattails, and people are eager to hear about her from another perspective. And while most of us know Anne from inside the secret annex, we know less about the life that came before—the family life, the deep connections with friends and neighbors like Hannah, who did briefly see Anne just once in Bergen-Belsen, and the other German Jewish refugees in their community. Some reviewers have even called My Friend Anne Frank the “sequel” to the diary.

Its reach is beyond anything either of us could have ever imagined sitting over our cups of tea, her speaking, me listening. It was a challenging task, a beautiful task—me listening and bearing witness to her words and, in the process, to paraphrase Elie Wiesel, becoming one, too.

Dina Kraft is opinion editor at Haaretz English and co-host of the podcast Groundwork, about Israelis and Palestinians working to change the status quo.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply