Arts

Film

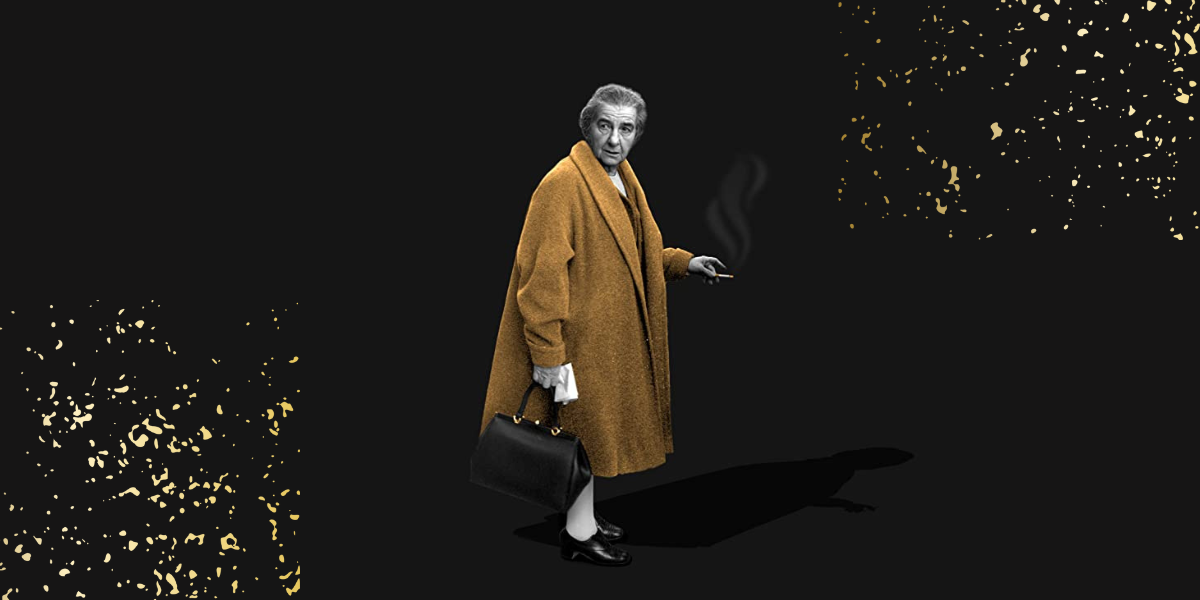

In the War Room With Israel’s Iron Lady

Many if not most people who watch the revelatory film Golda will come to recognize the truth of what its Israeli-born director, Guy Nattiv, told me in a recent Zoom interview: “History is not what they always taught us in school.”

The titular Golda, of course, is Golda Meir, who served as prime minister of Israel from 1969 to 1974. The first and, so far, only female Israeli head of state, Meir, sometimes called the “Iron Lady of Israel,” became a beacon for Jewish women around the world, though Israelis view her through a much more critical lens. The film, however, is not a biopic. Instead, it is a behind-the-scenes drama concentrating largely on the critical weeks surrounding the Yom Kippur War.

Nattiv, 50, was born six months before the war. “I grew up on the narrative that the Yom Kippur War was a complete surprise,” he said of the 1973 attack by a coalition of Arab forces led by Syria and Egypt. “We won, and it was a success.”

But that it was a “complete surprise” turned out to be untrue, he said, speaking from his home in Los Angeles. The devastating war happened in large measure because of a major intelligence failure, as recounted in the film. The government was aware that Syria and Egypt were massing troops along their borders, yet members of Meir’s war council refused to trust intelligence sources that said an invasion was imminent.

Adding to the shortsightedness was, as the film shows, Israeli hubris about its military superiority over its neighboring Arab countries. These miscalculations resulted in massive losses of both soldiers and equipment. At one point in Golda, the situation becomes so dire that Meir, played by Helen Mirren, turns to an aide and says: “If the Arabs reach Tel Aviv, I won’t be taken alive. You are to make sure of that.”

The film also portrays how, after the war, a commission was appointed to investigate who should be held responsible for the disproportionally high number of fatalities—the commission ultimately absolved Meir of direct responsibility. Nevertheless, over the last decade, according to Nattiv, newly unclassified documents reveal the tensions in the war room, details about the intelligence failures and Meir’s doubts around her decisions.

The unmasking of these truths is what makes Golda, which is set to open nationwide on August 25, so remarkable. Most movies value cinematic continuity over facts, but what Nattiv has done is trust that the story that took place out of public view is sufficiently powerful to stand by itself.

In part, the film’s success is a tribute to its lead. While covered in layers of prosthetics and makeup, Mirren fully captures the chain-smoking Israeli leader, both physically and emotionally. You see in her performance Meir’s no-nonsense toughness as well as the doubts she must have felt as someone with no military experience who must contend with the divided views and nonstop in-fighting among her all-male cabinet and military experts.

Filmgoers will also sense Meir’s weariness. She is secretly undergoing treatment for cancer, which she fears could impact her mental health. (In real life, Meir died of lymphoma just four years after she left office.)

“If you see the slightest sign of dementia,” Meir tells her trusted assistant, Lou Kaddar (Camille Cottin), “let me know. I can’t trust the flatterers.”

In the end, Meir emerges from the film as a tarnished hero. She wasn’t the best military leader, but it was through her efforts that the United States was convinced to replace Israel’s dwindling supplies at a time when President Richard Nixon was fighting a battle of his own over Watergate. Moreover, it was Meir’s close relationship with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, played by Liev Schreiber, that influenced the decision to delay officially announcing the cease-fire for 18 hours, giving Israel a chance to recapture territory lost in the battles.

Israel didn’t win the war; the Arabs lost it. Exhilarated by early success, Egypt moved further into Israel, thereby leaving Cairo unprotected and a flank exposed to Israeli fire. As Meir says in the film, “Knowing when you’ve lost is easy. Knowing when you’ve won, that’s hard.”

With this film, Nattiv and certainly Mirren should know that they’ve won.

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply