Wider World

Feature

The Women Fueling the Rise of #JewishTikTok

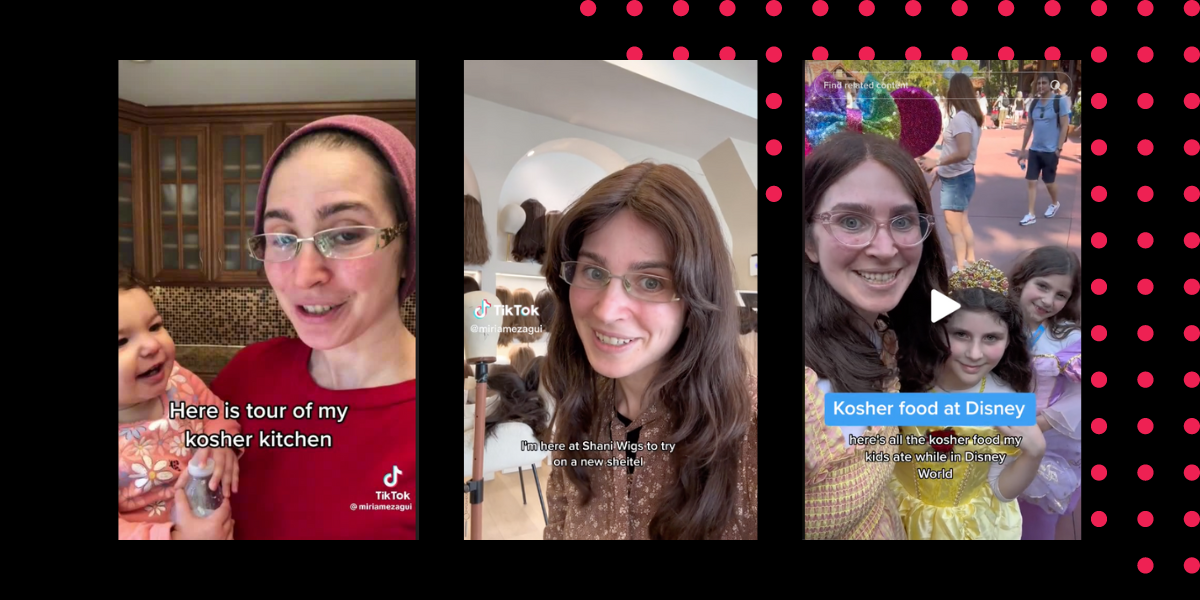

“Here’s all the kosher food my kids ate at Disney World,” Miriam Ezagui shares in one of the many TikTok videos she filmed during her family’s May trip to Orlando, Fla. As she lists off the kosher meals and snacks, her followers see her daughters—Naomi, Zahava, Aviva and Dassy, all wearing princess dresses—slurp down ramen noodles and munch on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches brought from home as well as enjoy popcorn and strawberry ice pops bought in the park.

When the family tried hot food at a Disney restaurant, which came double wrapped since it was heated in a non-kosher oven, Zahava made a face after taking a bite.

“She was not a fan,” Ezagui tells her acolytes.

If Ezagui’s name is unfamiliar to you, then you’re probably not among her 1.7 million followers on TikTok. The married 37-year-old, wearing a wig or headscarf in keeping with Orthodox practice, lets people into every aspect of her life, from her work as a labor and delivery nurse in Brooklyn, N.Y., to parenting four daughters to her marriage to Aron Ezagui, a paramedic.

Her reach on the platform is astounding. That TikTok—the app’s name is now synonymous with an individual video post—about kosher food at Disney World received 3.5 million views alone and over 400,000 likes. Meanwhile, the post’s comments section opened up a lively discussion. One user recommended a nearby kosher restaurant in the Orlando area. Another excitedly noted that she saw the Ezagui family at Disney World.

But not everyone had something positive to say.

“Just for once make them have normal kids’ food, you are in DISNEY, why go if you are not allowing them to enjoy their snacks,” one commenter chimed in.

“We don’t pick and choose being Jewish,” Ezagui replied to that comment. “We are Jewish 24/7 even while on vacation.”

For Ezagui, who behind her glasses and broad smile habitually exudes a calm, friendly and unpretentious presence on TikTok, her biggest motivation as a content creator is to educate people about her Orthodox way of life.

“I’m breaking down walls,” she said in an interview, “and I’m giving people a window into my life so that they can have a better understanding of how Orthodox Jews live.”

Ezagui is far from the only Jewish woman on TikTok, a platform that allows users to create and watch short-form videos on any topic. Originally called Musical.ly, the app was launched in 2014 by Chinese entrepreneurs, then acquired and renamed TikTok in November 2017 by the Beijing-based tech company ByteDance. Since then, TikTok has skyrocketed in popularity and amassed 150 million monthly users in the United States and more than one billion users worldwide.

The app has likewise attracted legions of Jewish content creators. Indeed, the hashtag #jewishtiktok has received 3.4 billion views to date. Among them are many Jewish girls and women of all ages sharing everything from cringy dating stories to SpongeBob SquarePants lyrics sung in Yiddish to glimpses of living in Israel.

Food, of course, is hugely popular. Among the Jewish women hosting the most-followed food accounts are Romanian-born social media recipe developer Carolina Gelen; Melinda Strauss, an Orthodox food and lifestyle blogger; and Anat Ishai, a Canadian whose specialty is challah.

Many performers and artists use the platform to grow their audience. Marcia Belsky, a stand-up comedian and musician, shares clips from her act in which she jokes about growing up Jewish in Tulsa, Okla. Libby Walker does impressions of a Jewish mother she has named Sheryl Cohen and reenacts funny summer camp memories.

Book blogger Amanda Spivack is committed to expanding her coverage of books by Jewish authors on TikTok and on Instagram, where she co-hosts the Matzah Book Soup book club. Among her recent recommendations were My Last Innocent Year by Daisy Alpert Florin and Endpapers by Jennifer Savran Kelly.

It’s no accident that there’s something for every Jewish person—or any person interested in Jewish culture—on TikTok.

“As Jewish users began creating and engaging with Jewish-themed content, TikTok’s algorithm gradually started amplifying and recommending such content to a wider audience,” said Tom Divon, a Ph.D. student at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who is researching digital culture as it relates to the Holocaust, antisemitism and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on TikTok.

He has noticed a recent change in TikTok from a platform purely for entertainment to one where users are engaging in serious conversations about history, identity and politics.

“One of the strengths of TikTok is its ability to disseminate information and spark conversations rapidly,” Divon said. “As more users recognize the potential of TikTok as a platform for meaningful discussions, the range and depth of these conversations are likely to expand.”

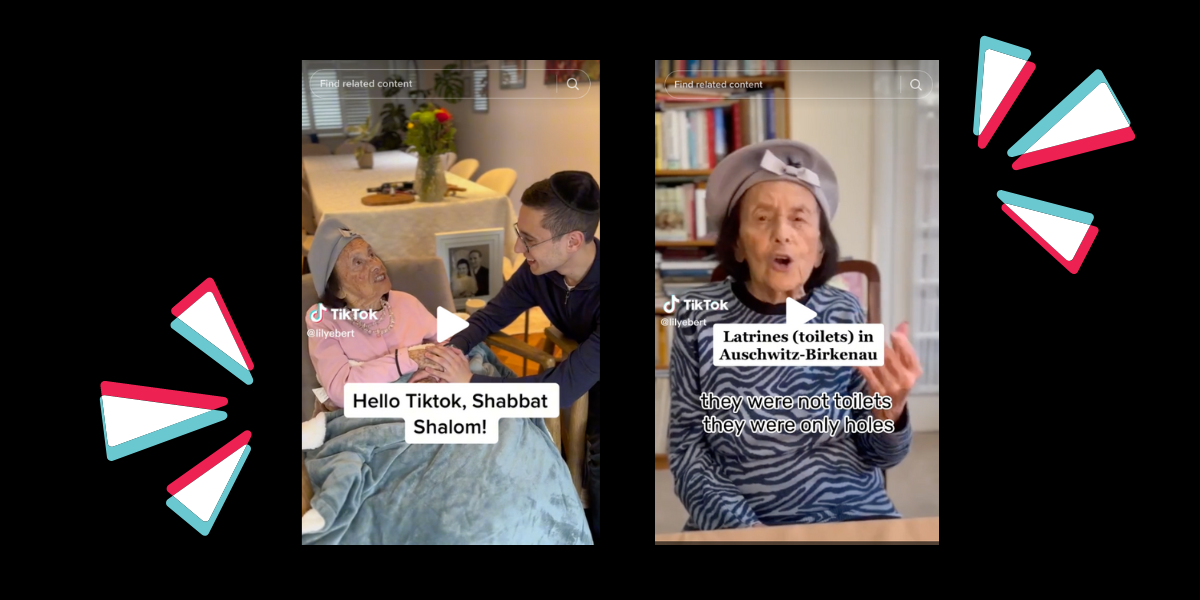

Auschwitz survivors Tova Friedman and Lily Ebert are part of this evolution. Each hosts a TikTok account—Friedman with the help of her 17-year-old grandson, Aron Goodman, and Ebert with her 19-year-old grandson, Dov Forman. Both women share their stories of survival, educate about the Shoah and answer followers’ questions.

“I was on the last train from Hungary to Auschwitz,” Ebert said in a TikTok shared on May 15, the day marking 79 years since the first deportation of Hungarian Jews. “There, they killed my mother, my brother and my youngest sister. I want from the world at least one thing: that this terrible tragedy should not happen again.”

Most TikTokers are decades younger than Ebert and Friedman. According to data compiled earlier this year by Comscore, a media analytics company, TikTok’s highest percentage of users are also its youngest: 32.5 percent of account holders are between the ages of 10 and 19.

Those numbers stand in stark contrast to the most recent data available from Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. According to Meta, only 3.9 percent of Facebook users are between 13 and 17, and its highest percentage of users—at 23.8 percent—are those aged 25 to 34. On Instagram, 8 percent of users are 13 to 17; and 30.8 percent, the highest percentage audience on the platform, are 18 to 24.

Sarah Haskell wants to show the world that not all religious Jewish women look and act the same. Using the handle @thatrelatablejew, the 23-year-old strives to be just that. While she grew up in an Orthodox home and continues to be observant, today she eschews religious labels.

“When I was younger,” she said during an interview, “I saw people online who were representing Judaism, and they were either rabbis or people who had a Jewish identity but weren’t practicing religiously. All of that is great, but I wanted to see someone who looks like me online—an average, modern Jewish person who incorporates Judaism in their life.”

Haskell, who has long blond hair and gray eyes, began creating TikToks during the Covid-19 pandemic in the bedroom of the apartment she shares with two roommates. The process, she said, “snowballed.” She now posts at least one video—it could be about touring a kosher supermarket with her mother or locating Star of David donuts at a kosher Dunkin—every three to four days and enjoys it so much that she has made a career out of social media. She currently works as the social media manager for a custom men’s suit company.

In a recent TikTok, Haskell discussed living in a Manhattan neighborhood popular among Jewish singles in their 20s and early 30s.

“Most synagogues in my area will have a kiddush after davening is over, and people tend to treat that almost like a dating mixer,” she said with a cheeky smile about her local Shabbat scene.

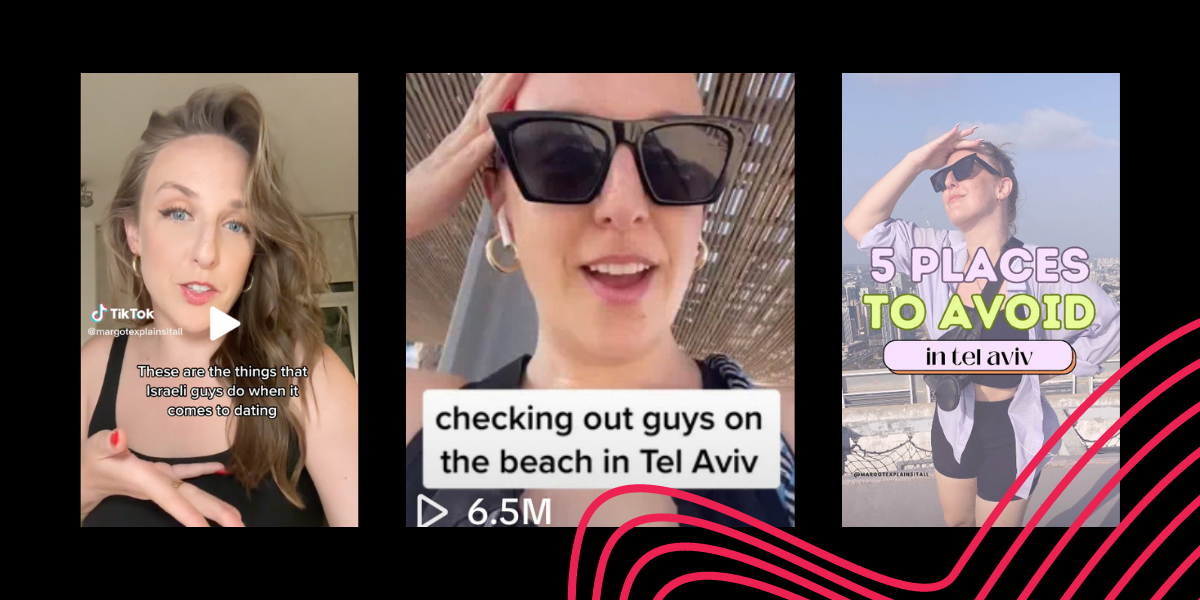

Thirty-four-year-old Margot Touitou also has something to say about the Jewish dating scene, a frequent topic both on her TikTok feed and on her podcast Kiss and Tel Aviv, which she describes as “the first and only podcast about dating, sex and relationships in the White City.”

On TikTok, she typically posts videos every two to three days that highlight the ups and downs of living and dating in Tel Aviv. She routinely offers advice to recent immigrants based on her own experience making aliyah from Denver 10 years ago and takes lighthearted jabs at Israeli culture—all done with a wry sense of humor.

“Here are four things that start on time in Israel,” Touitou, a freelance social media consultant and coach, said in a TikTok. On her list: loud construction beginning at 7 a.m.; drivers honking the second that a traffic light turns yellow (traffic lights change from red to yellow and then green in Israel); Israeli men hitting on female tourists the moment they arrive at the beach; and Shabbat.

“There’s ‘trauma porn’ on social media when it comes to Israel,” Touitou said in an interview on a day of intense rocket fire and airstrikes between Palestinian Islamic Jihad and the Israel Defense Forces. “No one needs to see another video of a rocket siren. It’s important to show the reality, but sometimes people just want to escape.”

Touitou said she accumulated 1,000-plus followers after only two weeks of posting videos, which could be attributed to a TikTok feature that allows creators to gain exposure to new audiences. Unlike with Meta, TikTok users, when they open the app, are automatically taken to their “For You” feeds, which spool endless videos from creators the user does not follow.

“On Instagram, I have a community, people who come back every time,” she said. “But on TikTok, I’m able to reach new audiences. The reach on TikTok is unmatched.”

According to Touitou, her videos usually take anywhere from five minutes to several hours to create. However, she added, one of her most popular ones, which has surpassed 6 million views, was made in 30 seconds. In the clip, Touitou is at the beach and says, “I just saw a guy who is so my type. Look!” She then points her camera at a big red flag.

Ezagui, the Orthodox nurse and mother, is a prolific TikToker who posts one or more videos daily. She said that it takes her about an hour to film and edit each 60- to 90-second clip.

As with most social media platforms, there are ways for TikTokers to monetize their accounts. Many consumer businesses pay top influencers to feature their products or services, for example.

Ezagui is a member of the TikTok Creator Fund, which compensates creators for well-performing videos.

The platform has not divulged exactly how it pays its contributors, but reports indicate that TikTok pays between 2 and 4 cents for every 1,000 views.

TikTok is also a great place to advertise your side hustle. Haskell promotes sweatshirts that she sells that are emblazoned with a Star of David. Ezagui advertises the natural childbirth class she teaches—“Birthing with Miriam”—to potential new clients.

It was while on maternity leave in December 2021 that Ezagui first began making videos about one of her passions: babywearing, i.e., carrying a baby in a woven wrap. But what began as a hobby while caring for a newborn soon evolved into something far more meaningful.

Last year, when The View co-host Whoopi Goldberg made a comment that the Holocaust was not about race, Ezagui, whose grandmother, Lilly Applebaum Malnik, is a survivor of Auschwitz, said that she realized that antisemitism often comes from a place of ignorance—so why not use her feed to educate? Her bubbe now makes the occasional cameo with her on TikTok to discuss her experience during the Holocaust.

Ezagui said she receives a range of questions about her religious observance from non-Jewish followers: “What is kosher? Why do you cover your hair with hair? Would you still accept your children if they didn’t want to be Orthodox?” She answers most, including about Jewish laws that govern a relationship between a husband and wife and talks openly about her miscarriages and breastfeeding in public. The one subject that she does not touch is politics.

“I make a point not to talk about anything political,” Ezagui said. “It’s something that people are constantly asking me, but I’m not here to be a political figure.”

But eschewing politics or other potentially sensitive topics is not enough to deter the haters. “I get hate every single day on the internet, from one angle or another,” Touitou said. “Whether it’s misogynistic if I’m talking about dating, or Jew hatred if I’m talking about my Jewish identity or Israel.”

According to Divon, the Hebrew University researcher, “TikTok does have community guidelines that prohibit hate speech, but not directly antisemitism” as a category for reporting.

TikTok is not the only online breeding ground for anti-Jewish bias and hatred of other groups. All social networks have become notorious for spreading hate speech, especially from “trolls”—people who try to instigate conflict and hostility online.

TikTok is unique, explained Daniela Jaramillo-Dent, an internet scholar at the University of Zurich, when compared to the Meta platforms because of its “duet” and “stitch” features that allow trolls to attack influencers by co-opting their content.

In a stitch, a user takes a five-second excerpt of a video previously posted by someone else and overlays that recording with their own audio and captions. A duet allows a user to create a split screen, showing their reaction to an existing video.

For example, user @itsandrewv shared antisemitic tropes in a duet created with a video that Haskell, the young Manhattanite, posted showing her family conducting morning prayers at an airport en route to Florida. “Jews run the world. Do you know why? Because they are smarter than everybody. Google it,” he said alongside a video of the Haskell family davening.

Divon noted that because Meta platforms have been around longer and have been the subject of governmental and international committees that impose fines for data breaches, the company has been more proactive in addressing hate speech than TikTok, though Meta, too, continues to face criticism for not doing enough to police speech.

Sabine von Mering, professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Brandeis University and co-editor of the book Antisemitism on Social Media, said that of all the biases on the major platforms, the most pervasive and toxic is sexism.

“There is a lot of racism and antisemitism, Islamophobia, you name it,” von Mering said. “But women are the prime target of hate on social media, and especially women who dare to speak up, like politicians, public figures, etc.”

“The great thing about TikTok, you’re reaching so many people who are not even Jewish,” Haskell began by saying when asked about her experience with trolls. “The downside of TikTok is they need to do a better job filtering out antisemitic content.”

Ultimately, she said, there aren’t enough hours in the day to report and block each troll. “Sometimes, I think, if I’m doing that, I’m letting them win,” she explained. “Why should I take hours of my time correcting them?”

Dealing with trolls and even death threats is a balancing act, said Ezagui, and she has had to grow thicker skin. “To say that it doesn’t affect me wouldn’t be completely true,” she said, “but it doesn’t stop me from doing what I’m doing.”

Touitou has a similar perspective. “I don’t think we’re going to end or solve antisemitism by showing up online,” she reflected, “but I do think we will combat it by just showing up as Jews and not letting people scare us away from using our voice.”

And then there are the messages of support from the communities these women have built online.

Haskell, who shares the story of her religious journey—rebelling against her strict upbringing as a teenager and later becoming more observant on her own terms—has attracted an audience of other young people who have similarly struggled with religious identity.

For her part, Touitou has fostered a community of Jewish Americans living and traveling in Israel who watch her TikToks for advice. Nevertheless, she said, being a creator can sometimes feel isolating.

“When you put yourself on the internet, you feel like you’re shouting into the ether,” said Touitou, who shoots most of her videos in her apartment or on walks through the streets of Tel Aviv, often wearing her trademark big black sunglasses and her dark blond hair casually swept up in a bun. “But when you actually meet the people whose lives have been impacted positively by your content—that’s why I do it.” She said she encounters followers almost daily who recognize her from TikTok.

Jewish TikTokers are now being recognized by more than their followers. In May, Haskell was invited to the White House to take part in a Jewish American Heritage Month celebration, where she filmed several TikToks.

Ezagui attended and posted from the premiere of A Small Light, a miniseries about Miep Gies, the Dutch woman who helped hide Anne Frank and her family from the Nazis.

And Touitou participated in the Tel Aviv Institute’s Jews Talk Justice training, where she and other influencers honed their expertise in speaking about their Jewish identities online.

“Social media has been an opportunity for so many people for whom normal media is not an option,” Touitou said. “Whether they’re a person of color or Jewish or queer, whom traditional forms of media often overlook. On social media, you can have a voice.”

Orthodox Way of Life

Miriam Ezagui @miriamezagui

Sarah Haskell @thatrelatablejew

Melinda Strauss @therealmelindastrauss

Niki Weinstock @niki_weinstock

Shani Lechan @shaniwigs

Alyssa Goldwater @alyssagoldwater

Moses & Zippora @mosesandzippora

Toiby @toibycontinued

Secular Jewish Lifestyle

Margot Touitou @margotexplainsitall

Raven Schwam-Curtis @ravenreveals

Religious Learning & Yiddish

Miriam Anzovin @miriamanzovin

Cameron Bernstein @c.o.bernstein

Rabbi Sandra Lawson @rabbisandra

Israeli Life

Yael Deri @yaelderiofficial

Anna Zak @anna.zak

Yuval Biton @yuvalbiiton

Holocaust Survivors

Lily Ebert @lilyebert

Tova Friedman @tovafriedman

Rosie Greenstein @theredheadofauschwitz

Comedy

Marcia Belsky @marciabelsky

Julie Rothschild Levi @officiallyjulie_comedy

Libby Walker @libbyamberwalker

Brooke Averick @ladyefron

Julia A @qveenjulia

Zara Zahava @Zarazahava

Based Jews @basedjewsoftiktok

Food

Carolina Gelen @carolinagelen

Anat Ishai @challahmom

Jamie Milne @everything_delish

Books

Amanda Spivack @its.amandas.bookshelf

Mental Health

Inna Kanevsky @dr_inna

Art

Dahlia Raz @dahliaraz

Fashion

Clara @tinyjewishgirl

Alexandra Lapkin Schwank is a freelance writer for several Jewish publications. She lives with her family in the Boston area.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Azi Crain says

Sad to see this magazine feature this creator who called the governments action Genocide. She never spoke about Israel before and has never shown herself to be a friend of Israel on her social media . Do better Hadassah.