Israeli Scene

Feature

Israel’s ‘Ethnic Democracy’

In almost all the videos of the United Nations’ November 29, 1947, vote on Resolution 181 (the “Partition Plan”), the passage of the resolution immediately cuts to Jews across the world celebrating, wiping tears from their eyes and, in Palestine, dancing in the streets. After 2,000 years, the Jews would once again have a state.

Those celebrants all understood that Resolution 181 called for the creation of two states, one Jewish and one Arab. What they probably did not realize, though, was that the United Nations specifically stipulated that “the Provisional Council of Government of each State shall…hold elections to the Constituent Assembly which shall be conducted on democratic lines.” The resolution then added a very significant second demand: “The Constituent Assembly of each State shall draft a democratic constitution for its State….”

The United Nations, in other words, made two clear demands: Both countries had to be democracies and had to hold elections “not later than two months after the withdrawal of the armed forces of the mandatory power.” That, the United Nations resolution explicitly stated, was to then lead to the ratification of a constitution in each country.

That the new Jewish state would be a democracy was obvious to everyone. The Zionist movement had been democratic from its earliest beginnings. By the Second Zionist Congress in Basel in 1898, women were voting and running for office, long before they could in any European country. The political institutions of the Yishuv had been democratic from their creation; the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine was, by the 1930s, a fully democratic state in waiting.

Jews in the Western Diaspora therefore certainly expected that Israel would be a democracy; they would have considered anything else a failed state from the outset. And now the United Nations had made democracy an explicit requirement.

Yet Resolution 181 went further, stipulating that in the democracies that were to emerge, “no discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants on the ground of race, religion, language or sex.” The resolution also required protection of religious holy sites as well as access to them.

Missed our webinar? Watch the recording here.

Missed our webinar? Watch the recording here.

On the surface, the emerging Jewish state seemed anxious to demonstrate to the world that it fully intended to comply with those international demands. Paragraph 13 of the Declaration of Independence, formally known as the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, proclaims:

The State of Israel will…ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

Given the yishuv’s apparent interest in illustrating its openness to these demands of the United Nations, it seems surprising that the Declaration does not contain the words “democratic” or “democracy.”

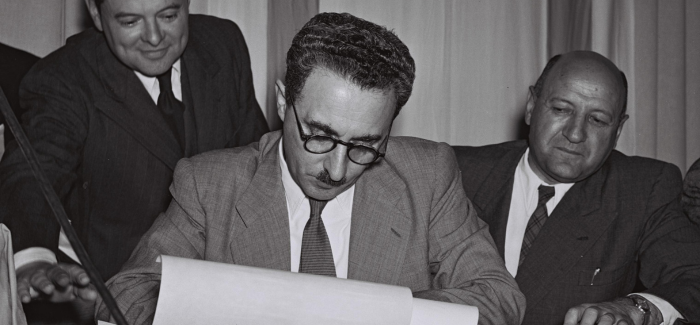

David Ben-Gurion was deeply committed to Israel’s being a democracy; about that, there is no doubt. Given that, here is what seems strange: Early drafts of the Declaration did include the word, but Ben-Gurion’s closer collaborators deleted it, and he chose not to reinsert it. Why?

Mordechai Beham, the young lawyer assigned the task of drafting the Declaration, began by studying and copying sections of the American Declaration of Independence. His first draft was richly peppered with Thomas Jefferson’s language. Is it possible that, since the American Declaration does not mention democracy, Beham assumed that Israel’s also had no need for the word?

READ MORE: Declaring the ‘Realization of the Age-Old Dream’

Perhaps. But the world was watching, and Resolution 181 was clear. Given that the United Nations resolution included the word “democratic” several times, later editors of the Declaration’s draft apparently felt that leaving the word out would be unwise. When Beham’s draft was passed on to Zvi Berenson—then the legal adviser to the Histadrut (still Israel’s largest labor union) and eventually a justice of the Supreme Court—Berenson added “democratic.” His proposed text defined the emerging Jewish state as “a free, independent and democratic Jewish state.”

But between Berenson’s addition and Ben-Gurion’s final wordsmithing just before May 14, 1948, the draft went through several additional edits. As the clock ticked down to the Friday afternoon declaration of statehood, Moshe Shertok deleted the word “democracy.” Had Ben-Gurion asked him to do so? Did he believe he knew what Ben-Gurion would have wanted?

Whatever the case, the Declaration was finalized with no mention of “democracy.”

What was Ben-Gurion’s reasoning? At the time, the “old man” (he was called that long before he was old) offered no explanation. But shortly thereafter, in September, he penned an entry in his diary that indicates that the deletion was no oversight. Essentially explaining the Declaration’s promise that Israel would be “a society as envisioned by the prophets,” he wrote:

As for western democracy, I’m for Jewish democracy. “Western” doesn’t suffice. Being a Jew is not simply a biological fact, but…also a matter of morals, ethics…. The value of life and human freedom are, for us, more deeply embedded thanks to the biblical prophets than western democracy…. I would like our future to be founded on prophetic ethics (man created in the image of God, love your neighbor as yourself—these foster an egalitarian life as in the kibbutz), on cutting-edge science and technology.

To be sure, Ben-Gurion, whose love for the Bible is now the stuff of legend, probably did prefer Amos and Isaiah as inspirations to Thomas Jefferson. He may well have believed that some of the values of “Jewish democracy” were embedded in the Bible.

Yet there were likely other considerations as well. “Democracy” was a Western notion, and in 1948, Ben-Gurion was cultivating relationships with both the United States and the USSR, which had voted in favor of Resolution 181 and the creation of a Jewish state. Was Ben-Gurion trying not to antagonize the Soviets? (Recall that Shertok, who deleted the word, would become Israel’s first foreign minister, at which time he changed his last name to Sharett.) Perhaps.

Still another possibility stemmed from the reality of the Middle East. The leaders of the about-to-be-declared state understood that Israel, once it came to be, was hardly going to have congenial neighbors. The country would be born in the crucible of war, and it would likely have to make complex, even painful choices. What if Israel were to decide to place Israeli Arabs under military rather than civilian authority (which was indeed the case from 1948 to 1966)? Would the world say it was not living up to its promise to be a democracy? Or might the term “democratic” open Israel up to the challenge that it could therefore not define itself as a Jewish state?

Might people ask whether a “real” democracy could accord everyone equal rights and protection under the law but still give preferential status to one religion or one ethnicity by making the Jewish holidays national holidays, making the language of the Jews the official language of the state, or by granting Jews—but not others—the automatic right to immigrate?

Here is what is often completely overlooked when we assess Israel’s democracy: While there was much to learn from America, Israel was never meant to be the sort of democracy that Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison had in mind for the United States. It was founded for an entirely different purpose; that purpose had to do with the future of the Jewish people, not with a political experiment in self-governance that had implications for the entire world, as was the case with the United States.

Though neither Israeli nor American Jewish leaders were ever inclined to stress this point, Israel was never intended to be a liberal democracy. Israel has always been something different, commonly called an “ethnic democracy.”

In an ethnic democracy, all citizens have equal claims on civil and political rights, but the majority group (Jews in Israel’s case) have some sort of favored cultural, political and, at times, legal status. The motivation for this type of democracy in Israel stems from the very purpose of the state, which was, as British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour had put it in the Balfour Declaration in 1917, to be “a national home for the Jewish people.” If America was devoted (in theory) to a universal vision of “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” whoever they might be and wherever they might have come from, Israel was a more particularistic project, about healing, protecting and cultivating the flourishing of the Jewish people.

Yes, Israel would be a democratic country, but not in the classic liberal democratic sense. And that is a critical distinction. One cannot understand some of what Israel does—such as passing a law declaring that it is the nation-state of the Jewish people when 20 percent of its population is not Jewish—without appreciating this fundamental difference between Israel and Western democracies.

I believe that Israel has made a critical mistake over the years in not being more explicit about its unique kind of democracy. Of course, it was convenient that Americans and Jews throughout the world saw Israel almost as a Hebrew-speaking, falafel-eating America. If America was (then) seen as a model for all the world to emulate, why not suggest—or at least implicitly encourage people to believe—that Israel was a miniature America? For those seeking to foster an affinity between the United States and Israel, or between American Jews and the Jewish state, encouraging that view might well have seemed strategically wise.

But it was a short-sighted strategy. Over the decades, and especially with the rise of a generation that does not recall the world in which Israel was created, that obfuscation has created expectations of Israel—throughout the West but especially among Jews in the Diaspora—that it could never meet.

The most obvious way to be explicit about the kind of democracy Israel would become would have been in a constitution—which Israel never wrote. Though Israel’s Declaration of Independence promised a constitution by October 1, that was wholly unrealistic. How could Israel debate and pass such a document in a mere four months?

Ben-Gurion never intended to push for a constitution. The just-born country had been cobbled together by communists, socialists and free-market capitalists; the religious, traditional and rabidly secular; those who hoped for a shared state with Jews and Arabs and those who thought that would be suicide. Trying to write a constitution would have highlighted the chasms between the visions of Israel among those who founded the state and could have toppled the entire fragile house of cards.

Yet America’s experience is ominously instructive here. America’s founders decided not to address the issue of slavery in 1789, when the Constitution was ratified. Seventy-two years later, the long-simmering disagreements exploded into a catastrophic civil war.

Israel today is just as deeply divided—over the role of religion in the Jewish state, the status of non-Orthodox Judaism, the relative power of the Supreme Court (seen as “left”) and the Knesset (now mostly “right”), who should be eligible to come to Israel under the Law of Return and more.

Might a constitution have settled some of these questions, thus avoiding the judicial crisis that has gripped Israel for the past several months? It is impossible to know. What is clear, though, is that Israel’s leaders would do well to look at America and to be reminded of how lethal the divisions at the heart of a young democracy can be.

Israelis need to find their own Abraham Lincoln—a leader with gravitas who can help a nation to heal, who can lead a national conversation designed to make difficult decisions and resolve long-simmering disagreements, and who can help shape a renewed nation that, we hope, will survive for centuries to come.

Daniel Gordis is Koret Distinguished Fellow at Shalem College in Jerusalem. This essay is an adapted excerpt from his new book, Impossible Takes Longer: 75 Years After Its Creation, Has Israel Fulfilled Its Founders’ Dreams? Copyright © 2023 by Daniel Gordis. Published by Ecco, with permission of Harper Collins.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] fabulous. Fortunately, there’s tons of content available online, too. You might begin with an excerpt adapted from Daniel Gordis’s latest book, Impossible Takes Longer: 75 Years After Its Creation, Has Israel Fulfilled Its Founders’ […]