The Jewish Traveler

Feature

The Best of Jewish Baltimore

The broad, shimmering expanse of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, a cove-like stretch of the Patapsco River, is unlike any other. Strolling the harbor promenade is a little like looking at a sculpture from multiple angles. Every step reveals a shifting skyline, new reflections of sky on water and different views of masts and smokestacks.

The Inner Harbor long served as a kind of maritime public square—a role that, judging from the area’s mix of Colonial-era and bold modern buildings, it first played since Revolutionary War days. From the U.S.S. Constellation, launched in 1854, to the newly unveiled Rash Field skate park and the arresting glass triangles of the National Aquarium, the harbor is itself a living exhibit of Baltimore’s social evolution.

Near the waterfront stand two of the country’s oldest extant synagogue buildings. Lloyd Street Synagogue, built in the Greek-Revival style in 1845, features the nation’s first Star of David rose window in its sanctuary, a design element later replicated in several other worship spaces.

When Lloyd Street congregants installed another synagogue first, a pipe organ, the instrument was considered too Reform-leaning for traditionalists, who built a breakaway shul next door in 1876. Chizuk Amuno, as it was then known, later became a founding member of the Conservative movement’s United Synagogue of America.

In the 1890s, members of Chizuk Amuno sold the building to the B’nai Israel Orthodox congregation, which worships there to this day as one of the more than 30 Orthodox shuls in Baltimore. Indeed, roughly one in five of the area’s 95,000 Jews identifies as Orthodox, twice the national average. That community owes its robustness in large part to the global prominence of Ner Israel, a 90-year-old yeshiva and rabbinical college and a pillar of the haredi Agudath Israel of America movement.

The yeshiva’s own trajectory—moving from Baltimore proper to suburban Pikesville—mirrors that of the larger Jewish community. After World War II, many Jews migrated from downtown to northwest Baltimore and its adjacent suburbs.

Another first in the nation was the opening in 1854 of the original Young Men’s Hebrew Association. This development helped to usher in Baltimore’s position as one of the central bastions of American Jewish life.

Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold and her sisters were among the earliest congregants at yet another of the nation’s oldest congregations, Oheb Shalom, established in 1853. Their father, the Hungarian-born Rabbi Benjamin Szold, had immigrated to the city in order to take over its pulpit. Both father and daughter influenced the course of American Jewry in their own spheres. Henrietta, of course, was a social activist and pioneering Zionist. Benjamin steered a centrist course at the helm of Oheb Shalom at a moment when a theological rift was brewing among Baltimore’s Central European Jewish immigrants.

The German Jewish Reform movement swelling in Europe was imported to Baltimore by newcomers who founded liberal temples such as Har Sinai, which opened in 1842. Ironically, Har Sinai merged in 2019 with Oheb Shalom, where, 170 years earlier, Benjamin Szold had emphasized stricter Shabbat observance and tradition to counter the community’s liberal tug.

Generations after those ideological conflicts receded, Baltimore retains a tight-knit neighborhood feel that inspired Jewish native sons like filmmaker Barry Levinson, many of whose movies are love letters to the Baltimore Jewish experience. Another is Leon Uris, whose best-selling novel Exodus was based on a repurposed Chesapeake Bay steamship used to transport early Zionists to Palestine.

Adopted son Gustav Brunn, a German Jewish refugee whose wife reportedly bought his way out of Buchenwald in 1939, influenced the city’s culinary scene soon after his arrival that same year. Brunn, who had operated a spice company in his native Wertheim, concocted a blend of herbs and spices—Old Bay Seasoning, now certified kosher by the Orthodox Union—that locals and tourists alike have for decades paired with the city’s signature dish, the decidedly unkosher Chesapeake blue crab.

A kosher seasoning dusted atop local treyf? It’s as good a metaphor as any for the contrasts and coexistence that define today’s Charm City.

Baltimore’s walkable downtown boasts distinct neighborhoods around the Inner Harbor. Fells Point is the most charming, with its cobblestone streets dotted with boutiques, bars and eateries. You’ll find a monument to onetime resident Frederick Douglass along with a preserved street of rowhouses—Douglass Place—that the writer built for African American tenants.

For the most iconic harbor view, hike west to the Federal Hill area, where Civil War cannons complement the vistas from Federal Hill Park. Just down the hill on the harbor is the Maryland Science Center, which features a planetarium and observatory.

Across the harbor from Federal Hill, the National Aquarium is a stunning modern building whose massive shark and dolphin tanks are among Baltimore’s top attractions. Nearby, the Baltimore Holocaust Memorial features a dark, flame-like abstract sculpture by Joseph Sheppard.

Both Lloyd Street Synagogue and B’nai Israel are now incorporated into the campus of the Jewish Museum of Maryland, whose two main galleries are filled with historical photographs, ritual objects and explanatory documents. Lloyd Street visitors can tour an ongoing excavation of a recently discovered 19th-century mikveh.

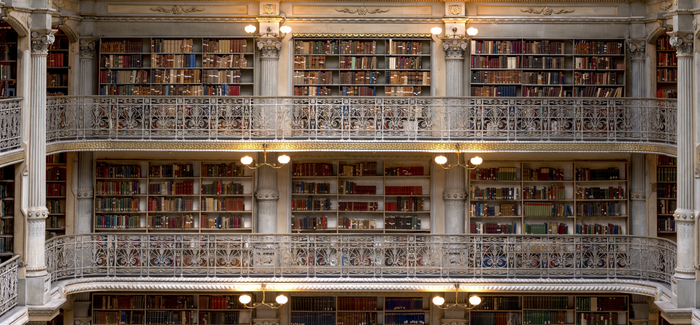

Take time to wander the Mount Vernon neighborhood, where cultural highlights include The Walters Art Museum, an impressive collection that spans ancient Egypt, Islamic manuscripts, medieval European armor and Russian imperial objects. Nearby, the George Peabody Library boasts one of the most magnificent library interiors anywhere—like a Venetian palazzo crossed with a lacy wedding cake.

The European art collection of businessman and civic leader Jacob Epstein, who died in 1945, have become central to the permanent holdings of the Baltimore Museum of Art. So, too, has the 20th-century French masterworks donated by Jewish sisters Claribel and Etta Cone, who brought back hundreds of paintings from their visits to Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso’s Paris ateliers.

You’ll need a vehicle to reach Baltimore’s most Jewish neighborhoods—the leafy, largely residential Park Heights and Cheswolde districts in the northwest city limits. Park Heights Avenue and the surrounding streets house myriad Jewish organizations, while kosher eateries cluster around Reisterstown Road in Park Circle. The Jewish communities extend northwest to the adjacent towns of Pikesville and Owings Mills.

East of downtown lies America’s first research university, Johns Hopkins, which was founded in 1876 and has been home to numerous Jewish scholars, including the erstwhile medical student and iconoclast writer Gertrude Stein, who was friends with the Cone sisters.

Hadassah Greater Baltimore counts over 4,500 members in six chapters scattered throughout the city and suburbs. Major projects include the operation of Scene II, a resale store located in Pikesville on Reisterstown Road, as well as the yearly gala, Cell-a-Brate, to raise funds for the Hadassah Medical Organization.

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply