Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: The Man With a Child’s Eye

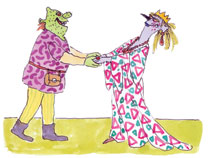

Final illustration for Shrek! (1990)Collection of the William Steig Estate ©1990 William Steig/Photograph by Richard Goodbody

In honor of the centennial of William Steig’s birth, an exhibition traces the life of the artist whose soulful, funny and biting characters and caricatures changed cartooning.

In the topsy-turvy world of William Steig, princesses prefer monsters to dazzling knights, goodhearted mice outwit sharp-toothed foxes, heroic dogs seek tikkun olam and children smash tightly capped bottles to release their imprisoned parents.

When he died in 2003 at 95, Steig left behind a legacy of over 1,600 cartoons and 120 covers for The New Yorker, 41 children’s books (he both wrote and illustrated most of them) and about 10,000 drawings, watercolors, sketches and doodles, many of which remained unpublished and private—until now. The Jewish Museum in New York (212-423-3200; www.thejewishmuseum.org) is celebrating the centennial of Steig’s birth with the first major exhibition of his work. The show includes over 190 original drawings as well as notebooks, letters and some reproductions where the originals could not be located. “From The New Yorker to Shrek: The Art of William Steig” runs through March 16 and will be at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum from June 8 through September 7.

Today, shrek—the star of a trilogy of films from DreamWorks Pictures—may be the best-known of Steig’s creations. Indeed, the ogre is well-represented in the show, in both illustrations from the book Shrek! (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and models and character studies for the movies. In one colorful book illustration on display, Shrek is holding his true love’s purple hands in his green ones: he with his hairy pickle nose, red eyes and grinning, pockmarked face; she with a black, straight-beaked nose and protruding blue teeth. “Oh ghastly you,” he declares, “with lips of blue/ Your ruddy eyes/ With carmine sties/ Enchant me.” It is both laugh-out-loud funny and a profound statement about human emotion—especially the true essence of love. That multileveled humor, grounded in childhood and bundled with poignant honesty, is what gives Steig’s work its brilliance.

Shrek hints at Steig’s Jewish identity (the word means “fear” in Yiddish). In fact, Steig sent faxes to the producers with his ideas for the first film: “Shrek is raising hell, killing dragons…. Every once in a while we see his mother worrying about him, like a Jewish mother.”

However, the artist’s background permeates his art in ways beyond the obvious. According to exhibit curator Claudia J. Nahson, Steig “represents an important generation of artists, children of immigrants who came to the United States with deep socialist values and acculturated into American society. It is very much a Jewish story.”

Steig’s parents emigrated from Lvov, Poland, in 1903, raised their four sons in the Bronx and encouraged the arts as a nonexploitive profession. Steig drew his first cartoons for his high school newspaper. He spent two years at City College of New York, three years at the National Academy in New York and five days at Yale University before dropping out. In 1930, the Depression forced Steig to use cartooning as a means to support his family. He began to draw for The New Yorker (at $40 a cartoon) five years after the founding of the magazine and for other magazines that published humor as an antidote to hard times.

His early art—most in pen and ink with color washes—channeled the optimism Jewish immigrants maintained despite their seamy tenement surroundings. In one piece for Collier’s magazine, a pot-bellied man in an undershirt looks out the window and, undeterred by the laundry hanging in his bedroom, declares, “What a beautiful morning!” In a 1935 New Yorker piece created by Helen E. Hokinson, a docent wearing a pillbox hat gives a talk to a group of well-dressed children while a spiky-haired boy in knickerbockers, drawn by Steig and pasted into the cartoon, grimaces on the side. “Pardon me, young man,” the docent calls, “are you a member of this Study Group?” Nahson suggests that Steig’s drawing might have reflected his own discomfort at entering the upper-crust world of The New Yorker.

As the immigrants he depicts make the transition to the middle class, Steig allows them to retain some of their Jewishness: Two content couples celebrate the New Year by raising their glasses “To life!” In another piece, a girl practices piano, and a composer’s bust on the piano utters a disgusted “Gevalt!”

Though he began as an outsider, Steig’s talent soon earned him a place as an all-American signature artist commissioned to do cheerful watercolor covers for the Fourth of July, football season, Columbus Day, Thanksgiving and Christmas.

The exhibition begins with a “preamble” that introduces Steig’s multifaceted career and establishes recurring themes. Picasso’s influence stamps itself on an untitled still life with figures (see cover) and a drawing of distorted faces. Animals and humans mirror each other: In “Ruminating,” a man and a dog with similarly long noses and parallel poses sit and think in a bucolic field. It is captivating to view original watercolors (not adequately reproduced in books published decades ago) in all their lush color and the pen-and-ink drawings as if they are fresh off Steig’s desk.

“The amount of feeling Steig can convey with a simple line is magical,” says Nahson.

For Steig, freehand drawing was the ideal, even illustration with repetitive characters was confining. He drew on whatever he could find, for example embellishing shopping lists with elaborate doodles. A display case features a wooden treasure box his daughter Maggie made to hold the doodles he gave her. In exchange for a fruitcake from his mother-in-law, he produced sketches of cats; the caption below a drawing of one feline family reads “The Catses.”

Steig integrated autobiographical details into some of his works, which Nahson has grouped together. “Sunday Painter” is based on his father, a house painter and artist. An illustration from the children’s book Brave Irene (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)—a seamstress hemming a pink ball gown, pins in mouth, needle in hand—could be a tribute to his mother, also a dressmaker. In the black-and-white “A Dream of Chicken Soup,” a mother flies down to spoon some chicken soup into her son’s mouth as he lies in a hammock. Steig’s father was imprisoned in Lvov for his socialist activities and his mother (Steig’s grandmother) brought him chicken soup in jail. Alpha Beta Chowder (HarperCollins), an alphabetical book of poems that Steig’s fourth wife, Jeanne, wrote and he illustrated, depicts “a lunatic living in Lvov” for the letter L.

Steig’s most autobiographical work, When Everybody Wore a Hat (HarperTrophy, published just before his death and based on a 1959 series he did for The New Yorker), is featured in the show’s preamble and epilogue. The book re-creates his Bronx childhood. “In 1916 when I was eight years old,” the narrative begins, “there were almost no electric lights, cars or telephones— and definitely no TV. Mom and Pop came to America from the Old Country…. Sometimes Mom and Pop quarreled. They spoke four languages: German, Polish, Yiddish and English. They spoke Polish a lot. When there wasn’t enough heat, Pop even fought with the radiator.” The accompanying illustration shows two terrified children clinging to each other as their angry parents argue.

The warring relationship between men and women was a constant theme of Steig’s art. His own parents fought constantly, and he himself went through three divorces before he married Jeanne in 1973. One wall covers the spectrum of relationships from courtship to unhappy marriages and painful partings. A 1959 cartoon shows a man reading devastating headlines in a newspaper, but he is unfazed until his wife yells at him. Even when couples look happy, their contentment comes at a price: In another cartoon, a cozy couple seems happy in their lover’s cottage but they are locked inside; a dog, bird, tulip and tree in the cottage’s yard are chained or caged. However, as Jeanne Steig points out in an essay in the show’s catalog (The Art of William Steig, The Jewish Museum/Yale University Press), “his doodles were often interlocked figures, sharing a nose or an eye. Were they trapped with each other or was the connection a comfort?”

Only much later in his life was steig able to express a view of love as pure and fulfilling. He drew a sketch for Jeanne with his right hand (he was a lefty) of a lion offering a flower to a maiden, and dedicated Abel’s Island (Square Fish), his Newberry-honored book about a love story between Edwardian mice, to her.

Steig’s revolutionary approach to cartooning seems obvious today—concept and illustration are one. But before he began working at The New Yorker, cartoons were a team effort: Writers offered the concepts and dialogues and artists provided the drawings. James Geraghty, The New Yorker’s first cartoon editor, once praised Steig in a letter: “Your genius is unsurpassed; for sensitivity and comic perception of the human plight, for loveliness of line, for constant renewal, constant freshness.”

“People often think of cartoon art as evanescent,” admits Nahson, “but Steig’s has a permanence. For almost every situation in life there is a Steig drawing. They keep reverberating in my mind.” Some of his captions became embedded in public vocabulary: “Mother loved me but she died”; “Public opinion no longer worries me.”

Steig also moved the subject of cartooning away from the upper class. A Peter Arno cartoon from 1927, for example, shows two wealthy men in top hats and tuxedos. “Are you carrying a cane tonight?” asks one. “No, I’m going to rough it,” the other answers. In contrast, Steig’s “Small Fry” series captured the street life of his Bronx childhood—a world that was disappearing. Rascals, hotheads, convicts, curmudgeons, cranks and complainers provide Steig with a rich source of humor, says Nahson, but they are also crucial to the artist’s insight that there is much to be dissatisfied with in the world.

Jeanne Steig recalls that her father-in-law liked to tell of a Polish Jewish jester, “a fabulous figure who impressed Bill mightily: the underdog who keeps the king in his place.” Faithful to his socialist roots and father’s teachings, Steig enjoyed taking a poke at snobbery, inequity and injustice. Often he drew “highfalutin’ folks looking downright foolish,” she adds. “Come to think of it, everybody looked foolish. That is how a serious clown sees the world.”

As world war ii approached, Steig created a spin-off of “Small Fry” called “Dreams of Glory,” in which children save the day. In a most blatant example, a cartoon from 1944 shows a child in a cowboy costume smirking while holding Hitler at gunpoint. It’s not surprising that, according to Jeanne Steig, her husband’s wish as a child was to save his parents. From what, he couldn’t pinpoint, but the theme recurs throughout his work. In Brave Irene, Irene’s mother gets the duchess’s dress ready for a ball, but when she falls ill, Irene must deliver the dress. The Zabajaba Jungle (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), a zany Sendakian tale, tells of a boy named Leonard who faces the perils of the jungle and rescues his parents from a bottle, perhaps evoking the Garden of Eden along the way.

The postwar years were the darkest in Steig’s life. Illness and divorce caused him to explore psychology and alternative medicine, which translated into a symbolic period in his art. He became both a patient and friend of psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich, a disciple of Freud. Reich believed that human neuroses are a result of energy-depleting stress and created an “orgone energy accumulator” to restore that energy. Steig illustrated Reich’s manifesto, Listen, Little Man! (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and then published his own, The Agony in the Kindergarten, bemoaning the abuse and repression of children in America. The sometimes chilling and melancholy images were not accepted at The New Yorker, but drawing them allowed Steig a freedom of expression that became a trademark of his more mature art.

He later returned to similar themes in a more lyrical, forgiving, optimistic and humorous fashion, says Nahson, and in his children’s books, he explores the healing power of love, art and nature. Children’s books gave Steig the chance to deal with loneliness, injustice, God, friendship, death and, often, terrible isolation. “They ended, so many of them, with the hero or heroine safe once more in the family’s arms,” writes Jeanne Steig in the exhibition catalog.

For children, delving into Steig’s universe offers a fantastic entrée into the mind of an artist who remained a child at heart. In the exhibit’s Sylvester, Shrek and Friends’ Reading Room, patterned beanbag chairs are inspired by furniture and clothing in the books. Portraits of characters hang on the walls, including Doctor De Soto on the ceiling, and a self-portrait from When Everybody Wore a Hat. The room also has curtained windows that replicate those in Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (Windmill Books) and Caleb & Kate (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). And, of course, there are Steig books to read.

In another area, sofas are covered in flowered prints from Doctor De Soto (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). A rug painted on the floor comes from Spinky Sulks (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Kids enter The Zabajaba Jungle Room through a dragon’s mouth and can manipulate magnetic butterflies, birds and frogs on a huge wall.

Given his total immersion in childhood, children’s books were a perfect fit for Steig. His first—CDB! (Simon & Schuster)—was not published until he was 60, but only a year later he won the prestigious Caldecott Medal for Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, the story of a donkey who finds a magical pebble and wishes to become a rock to escape a hungry lion. Sylvester is stuck in his rock body until his parents wish him back to his original form.

In Bad Island (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), published almost simultaneously, Steig indulged his imagination. He created fluorescent creatures “with stinging tails and clacking shells covered with grit and petrified sauerkraut” and a battle rotten to the core.

Steig casts animals as his protagonists in most of his picture books as a way to best communicate his ideas. As they embark on quests of self-discovery, pigs, mice, donkeys, frogs and dogs confront their emotions and survive through self-reliance. Improbable friendships (a mouse and whale in Amos & Boris, Farrar, Straus and Giroux), antiheroes (Shrek!), David-and-Goliath plots (Doctor De Soto) and magical doings (The Amazing Bone and Gorky Rises, both from Farrar, Straus and Giroux) embody concepts profound but never preachy.

Steig expressed his ideal of social justice in Dominic (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), an illustrated novel for older children; he later realized that the canine who “hated any kind of villainy” was based on his father. “By fighting the evil Doomsday Gang, nursing an elderly pig and sharing the treasure he inherits with other animals, Dominic engages in tikkun olam and embraces tzedaka,” says Nahson, giving the story her own spin.

In a seven-minute clip from the educational film “Getting to Know William Steig,” viewers can hear the artist’s own voice: “If you forget that you are writing for kids,” he says, “you are liable to write Moby Dick.”

Fittingly, the exhibit ends with side- by-side photographs of Steig at ages 8 and 90. Eight decades after his childhood photo was taken, he is still grinning boyishly.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply