Family

Feature

At Passover, Remembering My Grandma, and Her Chicken Soup

Buy a whole chicken. Cut it into eighths. Rinse and pat dry. Place the pieces in a deep pot and fill with water. Add a tablespoon of salt, a teaspoon of pepper. Bring it to a boil, then skim off the fat.

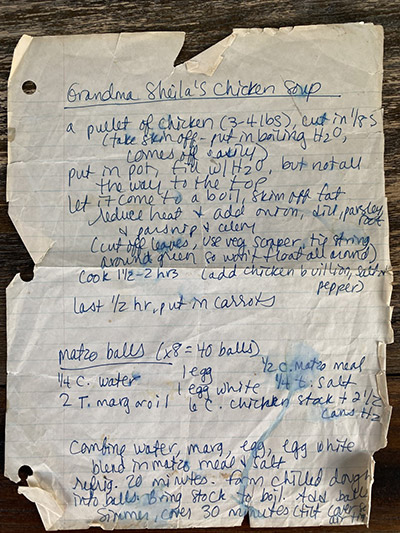

I stare at the recipe on lined notebook paper, some of the blue ink smudged by drops of water, the edges stiff and yellowed by all the time that has passed since I first wrote the words. I was 23 and living near Washington, D.C., and I couldn’t return to my family’s home near Detroit for Passover that year. Instead, Grandma Sheila taught me over the phone how to make her soup.

Today, I no longer need to look at the recipe to make it, but I do anyway. When I see my writing on the page, I can still hear her voice though she has been gone for eight years. “Buy fresh dill,” she would say. “Fresh dill makes all the difference.”

Flat parsley and, if you can find it, parsley root. A thick parsnip cut into chunks. A whole onion, quartered and floating. A handful of celery stalks, cut into fourths.

My kids have always loved carrots, so I include more of it than any other vegetable. I don’t add ingredients in steps, like Grandma did. I throw everything in as quickly as I can clean and chop.

The first time I made Grandma’s soup, I sat at the table in my quiet apartment in Bethesda, Md., lifted a spoonful to my mouth and closed my eyes. With the flavor of fresh dill on my tongue, I was home, sitting around the holiday table with everyone I loved, my grandfather’s jowls bouncing as he laughed, my grandmother smiling at his side, surveying all she’d created.

It’s not hard to make a pot of soup. It just takes time. I can also make quiche, bake muffins, roast meat in onion, garlic, ginger, ketchup and brown sugar. And then, when I sit with people I love, and they exclaim or sigh over the food I made, I feel like I have created a whole world in one meal.

I started cooking when I was a newly minted college graduate living in New York City. After taking two subway trains to my midtown office, working a full day and trekking home, cooking was one way to unwind with my roommate in the tiny apartment we shared. We’d strip down to bras and shorts, sip white wine, listen to jazz on the radio and pound chicken breasts. We’d boil water for pasta, peel and chop cucumbers, slice tomatoes, dice scallions, tear lettuce for salad. When we’d sit down to eat after all that effort, all the patient waiting for the food to be ready, whatever we made tasted like manna from heaven, as if the salt from our sweat had seasoned it.

Years later, when my children were babies, I never bought a jar of food. I mashed banana or avocado, made soup with sweet potato and zucchini. I shredded chicken onto their highchair trays, crumbled matzah balls for them to fist into their mouths. I loved the act of creating something nourishing from simple ingredients.

Since my grandmother was a skilled cook and baker, and my mother, just one generation later, didn’t enjoy making food from scratch, I assumed that most American women had moved away from home cooking during the first wave of feminism. However, the shift had started earlier, in the 1940s, when Campbell’s produced ready-to-eat meals to lighten the burden on housewives. This was a full 20 years before Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, and, as Michael Pollan wrote in 2009 in The New York Times, “taught millions of American women to regard housework, cooking included, as drudgery, indeed as a form of oppression.”

I don’t think Grandma felt oppressed in the kitchen. She didn’t cook solely to keep us alive, but to keep us loved. She had an ease about her when she prepared food, even when she made gefilte fish from scratch, which takes all day and smells up the house. It didn’t seem hard for her to create beautiful dishes; it seemed to relax, perhaps even invigorate, her.

Grandma taught me not to rush anything—whether recipes or the routine of daily life. It has taken me years to embrace her message. While I wait for salmon to cook, I can fit in three other activities or pause in the silence. I’ve learned to pour a glass of wine, put music on and feel the beat while my creations simmer.

In Grandma’s kitchen, a little radio hung from the underside of a cabinet. She’d tune it to a classical station and hum along. Every morning, she’d spend an hour applying her makeup and arranging her hair that was washed weekly at a salon. She’d choose an outfit, secure the necklace with child-shaped pendants enumerating her great-grandchildren (18 by the end of her life), enjoy a cup of coffee and a bite of breakfast.

Once I had returned to the Detroit suburbs to raise my own family, Grandma would drive to my house with treats for my four children—small plastic bags each containing exactly the same number of M&M’s plus a Dum Dum lollipop and a tiny box of raisins. She and I watched my kids build forts from blankets and pillows, jump in puddles, pump their legs on swings. We talked about my work, my parenting, my marriage, and I asked her about her life—anything just to hear the cadence of her voice and the wisdom in her words.

In 42 years, though, we never cooked together. Grandma prepared feasts for me, and later I made meals for her. Indeed, after Grandpa died, she came to my house for Shabbat meals that featured her recipes as well as some of my own.

I have inherited her cookbooks—The Settlement Cook Book by Lizzie Black Kander, A Treasure for My Daughter from a Hadassah chapter in Montreal and The Jewish Cook Book by Mildred Grosberg Bellin—with her cursive scrawled in the margins or on slips of paper.

“Enjoy the process of making something,” I imagine Grandma saying to me. “Let it take the time it needs. Watch how the flavors come together, relish the magic of satisfying those you feed.”

I learned recently that the word “restaurant” comes from the French verb restaurer, to revive or restore. First used in the 16th century, “restaurant” referred to a soup sold by street vendors as a cure for exhaustion—a remedy so sustaining that it changed the language.

On the same weathered paper as Grandma’s soup recipe are her instructions for making matzah balls. Sometimes I get them perfect—fluffy and light. When I rush the process, they end up hard and heavy, a struggle to cut with a spoon. When I make them right, Grandma whispers her approval in my ear, watching over my shoulder as I dip my hands in cold water before forming each ball. She’s reminding me to slow down, that good food takes time.

Lynne Golodner is the author of eight books and a writing coach, marketing entrepreneur and podcast host. She lives in Huntington Woods, Mich., with her husband and a rotating number of their four grown children.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Debbie says

Beautiful words and a wonderful tribute to your Grandmother.

Flora Goldfarb says

Lynne, I started to read this without looking at the credits. It touched my heart and as I continued to read and remember my Mom’s recipes and my girls using my recipes, I was touched by your beautifully, thoughtful holiday message. Have a wonderful holiday. Flora

Karrie says

Great article! You hit my chicken soup heart in the most warm and tender way. I can’t stop thinking about my mom and her recipe, about family gatherings… Thank you!

Is this an excerpt from a book?

Margo says

I LOVE THIS ARTICLE! The picture of you and your Grandma is just beautiful. I might possibly have known her as I come from Northwest Detroit and most likely am close to her age. I wonder what her maiden name was. . . ? Your thoughts- a soliloquy really- are a wonderful reminder to your readers to slow down and enjoy what they are doing. Take the time to put the love into it – hard for many of us to do because in today’s life we are so incessantly busy with a zillion different things.