Family

Hadassah, Tipat Halav, My Mother and Me

The two pieces of paper were yellowed and frayed and looked like they might easily disintegrate. My brother found them wedged underneath the last drawer of my mother’s now empty file cabinet. After my father’s recent death, the file cabinet along with the rest of my parents’ things were being hauled away as we prepared to sell their home in Los Angeles.

“I think you’ll want to see this,” he said as he carefully handed me the papers.

First, I saw what looked like my original birth certificate. “Place of Birth,” the certificate read in Hebrew. And on the dotted line in blue ink were the words “Beit Holim Hadassah” in Tel Aviv.

Hadassah. I’d known the place of my birth all my life but hadn’t given it much thought. Although I was born four years after the birth of the State of Israel, I’d immigrated at the age of 2 with my parents to the United States. Long ago, my mother had given me my American naturalization papers, but not the birth certificate. Hadassah to me was part of a vague family anecdote about my religious grandfather who’d walked across Tel Aviv in the heat wave of an August Shabbat to see his first-born granddaughter.

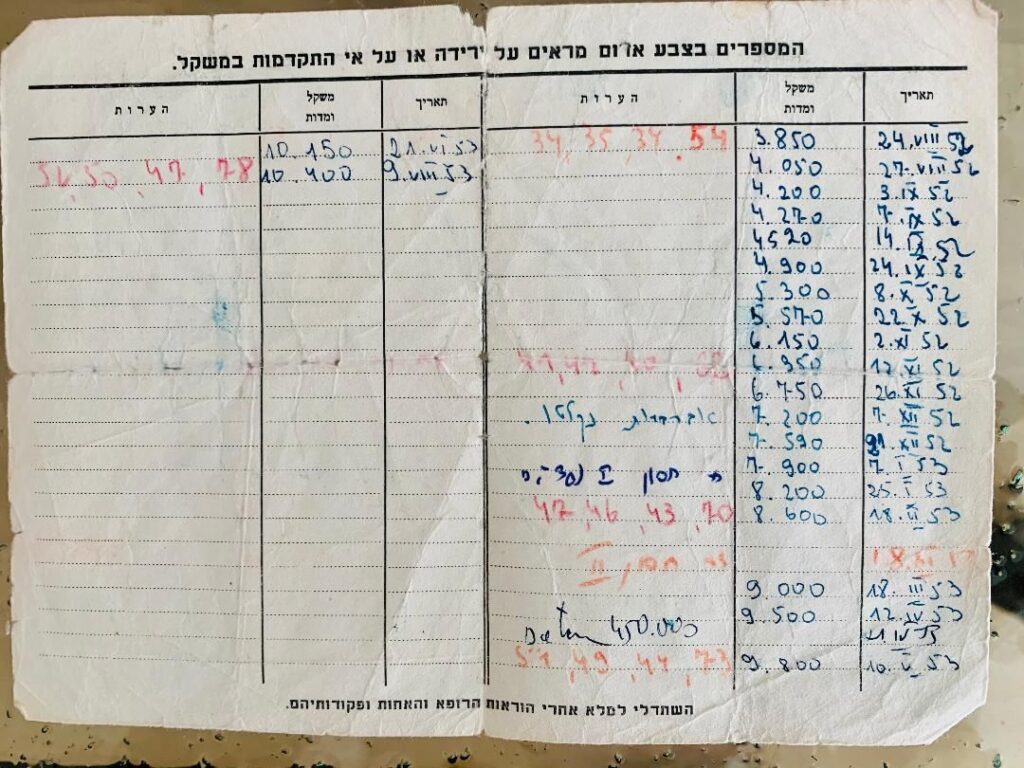

But then I looked at the second document, a folded pamphlet that my mother had also kept all these years. It took me a few minutes to decipher exactly what it was. It appeared to be a log, in my mother’s handwriting, of my weekly weigh-ins at a Tipat Halav, or “Drop of Milk,” clinic—one of several centers that had been pioneered by Hadassah starting in 1921 and that continue to welcome mothers and babies to this day under the auspices of the Israeli Health Ministry, at facilities throughout the country.

Why would she keep that? My mother, Yael, a sabra and a veteran of the Haganah, practical to a fault, wasn’t a keeper of many things. Unlike my father, who’d kept every scrap of paper, my mother saved and treasured little. “I don’t need to keep a lot of stuff,” she’d claimed as her mantra. So why this piece of paper that had somehow fallen to the bottom of a file cabinet?

I looked at the fragile pamphlet closely. “Bring this to your weekly visit,” it said in Hebrew on the cover. Inside, some entries had been smudged, but most were remarkably clear. Each one had a date and a weight in kilograms, blue signifying a weight gain, red signifying a loss. There were also entries for vaccinations. It seemed from the form that I had thrived and gained the proper weight without too many dreaded red entries. On the back was a half-page of instructions for new mothers. “Breast milk is the best food for babies.” “Make sure the baby can breathe properly while you’re nursing.” “Your baby will be happy and healthy if you bathe him every day.”

But I had to laugh when I read one of the last pieces of guidance. “Don’t ask your neighbors for advice when you have questions. Ask the doctor or the nurse.”

Before Tipat Halav, the infant mortality rate in pre-state Israel, first under the Ottoman Empire and later under the British Mandate of Palestine, was one of the highest in the world. Beginning in 1913, Henrietta Szold’s groundbreaking work around maternal health and the eventual establishment of mother and baby clinics helped dramatically reverse those numbers.

In 1952, the year I was born, there were still about 40 deaths per thousand live births in Israel (in 2020, the number was 2.48). Now, I wonder whether I could have been one of those statistics if my mother had not visited a Tipat Halav clinic. Those centers served as a place where new mothers could not only get support and counseling, along with milk for those who couldn’t breastfeed, but also where they could meet other young mothers and commiserate about diapers, husbands and interfering mother-in-laws.

That brings me back to the pamphlet my mother kept for decades. It didn’t have the legal significance of the birth certificate, but in that document was the evidence of another side to my no-nonsense mother. I like to think she kept it because it reminded her of those first days of motherhood, the combination of wonderful moments, the sleepless moments, the miraculous, treasured, but fleeting moments.

I was too busy with my own sense of overload when I had my children to reflect on how my mother felt when she had me. Sadly, she’s been gone for almost six years now, and I miss her every day. Discovering the pamphlet was like recapturing a small drop of time. I can now imagine her as she was then, a first-time mother, both happy and overwhelmed, walking or taking the Egged bus to her neighborhood Tipat Halav clinic with me in tow.

Leora Krygier is a former Los Angeles Superior Court judge. Her second-generation Holocaust memoir, Do Not Disclose: A Memoir of Family Secrets Lost and Found, will be published in August.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Randi says

Exactly what I needed to read on Mother’s Day. A good reminder for every child to reflect on the love and care our own mothers bestowed on us. Leora is a wonderful story teller with a big heart!

Karen Bloom says

Beautiful story, beautifully written. Thank you for sharing it with the world.