Arts

Jewish Arts Institutions Respond to Racial Injustice—and Covid-19

For the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education in downtown Portland, geography is destiny.

So too, it turns out, is architecture.

The museum, which has slashed its $1.3 million budget by about a third during the Covid-19 crisis, is housed in a graceful, light-filled structure built in the “Chicago school” style, with its distinctive grid forms and bands of windows. The museum’s large, ground-floor windows wrap around a corner that faces a city park, not far from where Black Lives Matter protests roiled Portland over the summer and fall.

As the pandemic wreaked havoc on Jewish museums and cultural institutions across the United States, forcing closures, steep declines in revenue, layoffs and budget cuts, officials and curators at the Portland museum looked within for ways to answer this fraught moment. Or, in this case, without.

“Our windows,” said Judy Margles, executive director of the museum, “are [prime] real estate.” In terms of exhibition space, the museum began to face the street, or “blast outward,” as she put it. “We’ve turned things inside out,” she added.

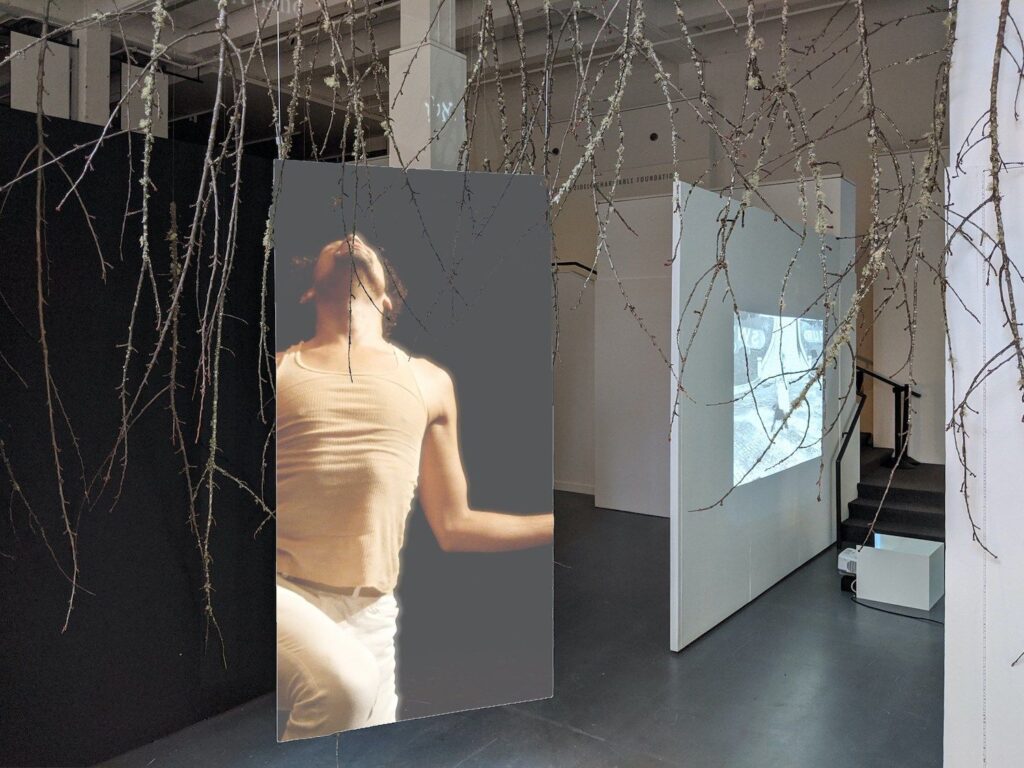

When the museum was closed for in-person attendance throughout the summer and fall, its windows became gallery space for the exhibit “Shelter in Place.” Passersby could peer in and glimpse dancer Adam W. McKinney’s mixed-genre installation, which brought together themes of Sukkot, racial injustice and the historical traumas suffered by the African-American and Jewish communities through photography and films of McKinney’s interpretive dances. McKinney is the first Jewish artist of color to have exhibited at the Oregon Jewish Museum, which opened in 1989. The exhibit closed in November but is still available for viewing online.

The Portland museum’s pivot to a fresh way of conceiving and displaying artwork is playing out at institutions all over the country. Scrambling to both stay connected to audiences during the pandemic and remain relevant during a time of significant social upheaval, many museums are attempting to address current issues while moving their programming online. And the moves are touching off a larger conversation about the role of Jewish museums amid the national reckoning on racial justice.

In Tucson, Ariz., the Jewish History Museum & Holocaust History Center has forged strong ties to the nearby historic Southwest Barrio Viejo neighborhood, where the city’s Mexican heritage is evident in brightly colored adobe homes and Mexican eateries, said Sol Davis, who was executive director of the museum until December, when he left to become director of the Jewish Museum of Maryland. This connection helped put issues of immigration front and center at the museum, whose building was still closed for in-person programming as of December.

In March 2020, the museum began using its courtyard as a staging ground to provide boxes of groceries as well as pro bono legal services for those hit hard by the pandemic. The outdoor space is also the site of an immigration and human rights-themed exhibition, in connection with the New York-based arts incubator LABA: A Laboratory for Jewish Culture. Called “Clamor in the Desert/Clamor en el Desierto,” from the phrase in Isaiah “kol koreh bamidbar,” a voice cries out in the desert, the exhibit by Argentinian Jewish multimedia artist Mirta Kupferminc depicts an open-sided, sukkah-inspired structure made from what look likes metal fences, an echo of the Southern border wall. Postcard-sized photographs of refugees’ eyes and text of their immigration stories in multiple languages hang from one side, beckoning viewers as if from the other side of the border.

As they weather the corona-virus storm, arts institutions are facing what Melissa Martens Yaverbaum, executive director of the Council of American Jewish Museums (CAJM), described as “an existential upheaval.” Particularly hard hit are the centers with small endowments that depend on admissions fees and gift shop sales for the bulk of their revenue. One such place is the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Seventy-five percent of its $11.5 million operating budget comes from such income; by April of last year, the museum laid off or furloughed more than 100 full-time and part-time staffers and reduced its budget by 70 percent.

In May, in response to the financial needs in the Jewish arts and culture field across the United States, a consortium of five Jewish foundations working with the Jewish Funders Network launched the CANVAS initiative, which funneled more than $900,000 to the Council of American Jewish Museums, the Jewish Book Council, LABA and other groups to distribute to Jewish institutions and individual artists.

Despite the hardships, museums are finding a way to respond to this moment.

“Jewish museums,” Yaverbaum said, “have been using this pause to recalibrate programs to deal with issues of racial justice and, in Tucson, the immigration narrative.”

Davis, the former executive director of the Tucson museum, agrees. “This is a critical conversation we’re having,” he said. “I think culturally specific museums have a real opportunity to draw on the history of American Jews as being active in the public arena around issues of justice, civil rights, the labor and LGBT movements.”

In October, for example, Miami Beach’s Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU, affiliated with Florida International University, launched a virtual series called “Black Lives in a Jewish Context” in collaboration with the university’s Steven J. Green School of International & Public Affairs. The series features online lectures, films and conversations between scholars, clergy and historians. One program in the series explores the contributions of Jewish songwriters to tunes used in the Black community around the civil rights movement, such as Abel Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit,” a haunting tune about lynching made famous by jazz singer Billie Holiday. Other topics include the Ethiopian Jewish experience in Israel and how anti-Semitic and anti-Black narratives have been historically connected.

Back in New York, by mid-September, the Tenement Museum was once again offering its popular walking tours of the Lower East Side, thanks to an emergency appeal that raised nearly $450,000. It has also brought back furloughed full-time staffers. In spring of this year, it is slated to launch a new tour of the all-but-forgotten Black presence in the neighborhood, titled “Reclaiming Black Spaces.”

Part of the larger push to reinvention is making sure that changes not only impact the museum’s walls, but its boardrooms, too. Two of the country’s most high-profile Jewish arts spaces, the Jewish Museum in Manhattan and the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, are looking to address the lack of diversity within their mostly white and upper-middle-class professional staff.

The Contemporary Jewish Museum is “developing an Anti-Racist, Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access working group comprised of staff members from all levels of the organization, which is designed to address issues of systemic racism internally as a first step toward rethinking and redeveloping the museum’s external programming,” a spokeswoman said in an email interview. It will also participate in Facing Change, an initiative led by the American Alliance of Museums

to help diversify museum boards.

Meanwhile, the Jewish Museum, where some staff members penned an open letter in June decrying the institution’s lack of diversity, has formed a 30-member internal anti-racism working group. The museum is also looking to boost the number of paid internships for would-be curators “as a way to diversify the internship pool,” said Claudia Gould, the museum’s director.

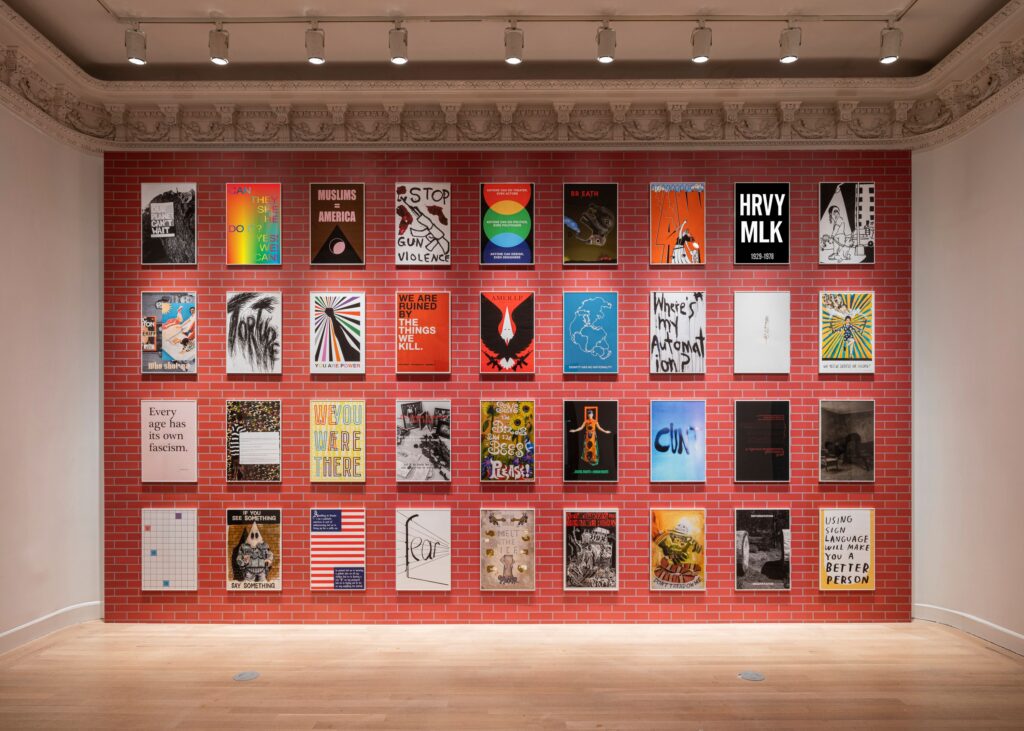

The current show at the Jewish Museum, which re-opened to in-person visitors in October, speaks presciently to the current moment, though it was planned several years ago to address the surge in anti-Semitic incidents across the country. Curated by New York artist Jonathan Horowitz, “We Fight to Build a Free World,” the title taken from a painting by Jewish artist Ben Shahn, includes more than 80 works in a variety of disciplines. It juxtaposes older works that deal with historical bigotry with contemporary pieces on the subject.

at New York City’s Jewish Museum. Photo by Kris Graves.

The exhibit speaks to the uniqueness of the Jewish experience but casts anti-Semitism alongside other forms of historical oppression. And it tracks with a trend in Jewish museums to straddle the particular and the universal when it comes to interpreting Jewish life.

“Jewish museums and Holocaust museums are already natural centers for discussions of anti-Semitism, hate crimes and genocide—especially as they pertain to Jewish history,” Yaverbaum, the Council of American Jewish Museums’ executive director, said. “I think there is tremendous potential for museums to have an authentic role in the public conversation about racism and justice—if handled with nuance, fluency, expertise, the right partners and the right content points.”

While Jewish museums have taken a financial hit in 2020, most have remained “intact,” as Yaverbaum put it. But she has deep concerns for 2021. “This year is going to put museums to a different kind of test—more of an endurance marathon than a sprint. This is when we may see the results of possible mergers, new configurations or new ways of consolidating the work or changing the expression of content.”

Such collaborations are already in the works. As winter turns to spring, the outdoor and window installations that began in Portland and Tucson will spread across the country in time for Passover. Spurred by commissions from Dwelling in a Time of Plagues, a collaboration among several Jewish arts organizations that included both McKinney and Kupferminc’s exhibitions, Jewish artists are creating works based on the themes of the Festival of Freedom. The pieces will conform to the demands of social distancing and be shown at various museums. And in keeping with these charged times, Yaverbaum said, they’ll reflect on a “contemporary issue that the holiday may shed light on—justice, climate change, immigration.”

Jewish art lovers can be assured that their favorite museums are still able to supply plenty of culture to be consumed, even if mostly via computer screen. And the warming months ahead bring hope of another chance to return to a real-life museum, or at least the outside of one. It should feel like a shockingly new—and joyous—rite of spring.

On View

Dwelling in a Time of Plagues

The website includes virtual tours of “Shelter in Place” and “Clamor in the Desert/Clamor en el Desierto” as well as other related exhibits throughout the United States, including upcoming Passover-themed displays.

“Clamor in the Desert/Clamor en el Desierto”

The outdoor installation will remain at the Jewish History Museum & Holocaust History Center in Tucson, Ariz., through the spring.

“Black Lives in a Jewish Context”

The series from the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU will run through the spring.

“Reclaiming Black Spaces”

Information about this and other Lower East Side walking tours is available on the Tenement Museum website. The site also features virtual tenement tours.

“We Fight to Build a Free World”

At the Jewish Museum in New York, N.Y., through January 21, the exhibit is also available for online viewing at the museum’s YouTube channel.

Robert Goldblum is the former managing editor of The Jewish Week.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Brian says

Great round-up Robert. Sounds like it would make a great framework for a road trip.