Arts

Core Concepts at Jewish Museum Berlin

Most Jewish houses have at least one: a mezuzah, nailed to a doorpost and containing the Shema, the declaration of God’s oneness and of Jewish identity.

The Jewish Museum Berlin’s new core exhibit—over two years in the making and officially launched on August 23—opens with the Shema writ large on the wall of a display, as if to say: “This is a Jewish space, this is our gate, you are all welcome to learn within its walls.”

On its first day, the exhibit, “Jewish Life in Germany: Past and Present,” was sold out. And that’s no surprise. Since its opening in September 2001, the museum, the largest of its kind in Europe, has been one of Germany’s most popular cultural institutions, with some 11 million visitors in its first 16 years, most from outside Germany.

It has also been one of the most controversial, earning both ire and praise for its handling of hot-button issues in shows and public events. Some critics have derided the museum for exhibits that stressed the assimilation of German Jews rather than their Jewish identity, notably in a 2005 exhibit on “Stories of Christmas and Hanukkah.” Others claimed that programming was politically biased to the left and anti-Israel, such as a 2017 exhibit about Jerusalem that some contended reflected a Palestinian narrative. The previous director resigned in 2019 after sending out a tweet that was seen as defending BDS.

The original permanent exhibit was also described as shallow, overwhelmed by the building’s famously daring design by renowned architect Daniel Libeskind. Indeed, ARTnews magazine recently described the old exhibit as “too full” and “a stew in which the individual ingredients disappear into a murky whole.”

In a kind of reverse metamorphosis, the flashy exhibit of the past has molted into a subdued, more contemplative and, perhaps deeper, essence.

“Jewish Life in Germany” was developed by a museum team led by chief curator Cilly Kugelmann and designed by the architectural firm Arbeitsgemeinschaft chezweitz GmbH/Hella Rolfes. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, sanitation stations now appear throughout the galleries, masks are required and there is a cap on daily attendance. In addition, the opening of a children’s exhibit—“ANOHA, The Children’s World”—has been delayed. A space for temporary exhibits will open in spring 2021.

Despite a “greatly reduced” number of objects on display compared to the previous core exhibit, noted Hetty Berg, the museum’s new director, the new exhibit still covers significant ground: 1,700 years of Jewish life in Germany over almost 38,000 square feet, with many multimedia and interactive elements.

In contrast to the strictly chronological previous exhibit, the current core is much more than a walk through the past. Five displays on German Jewish history, or epochs, are interwoven with eight sections dedicated to themes, among them: “Torah”; “The Jewish Object,” which highlights Judaica; a “Hall of Fame” of 70 Jewish personalities from throughout history; and “Art and Artists,” with pieces by Jewish artists from the 1820s to 1940s. This juxtaposition of themes and history creates a sense of timelessness and contemplation.

“The museum not only has the task to present German Jewish history from the past up to today,” said Berg, acknowledging that the historical context makes that task difficult, it must also engage with ideas important to society today, such as exclusion and belonging, identity and diversity, migration and acculturation. And, added Berg, who came to Berlin in April after 30 years as museum manager at the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam, “it can also be a place where those questions and themes are discussed in a respectful and open manner.”

Torah scrolls bookend the exhibit, placed near the entrance and exit. They represent “the unchangeable” core of Judaism, said Judaica curator Michal Friedlander.

Older artists bring hopeful messages to their audiences.

A massive sculpture by German artist Anselm Kiefer, called Shevirat ha-Kelim (Breaking of the Vessels), holds a place of honor in the area on Jewish mysticism. Kiefer used metal, glass and other materials in his interpretation of the kabbalistic teaching of Isaac Luria (1534 to 1572), who said that God’s creation of the world caused a disharmony that requires human intervention for healing. The work resembles a bookcase filled with coverless volumes, their leaves loose and fluttering. Shards of glass surround the central structure like an untraversable moat.

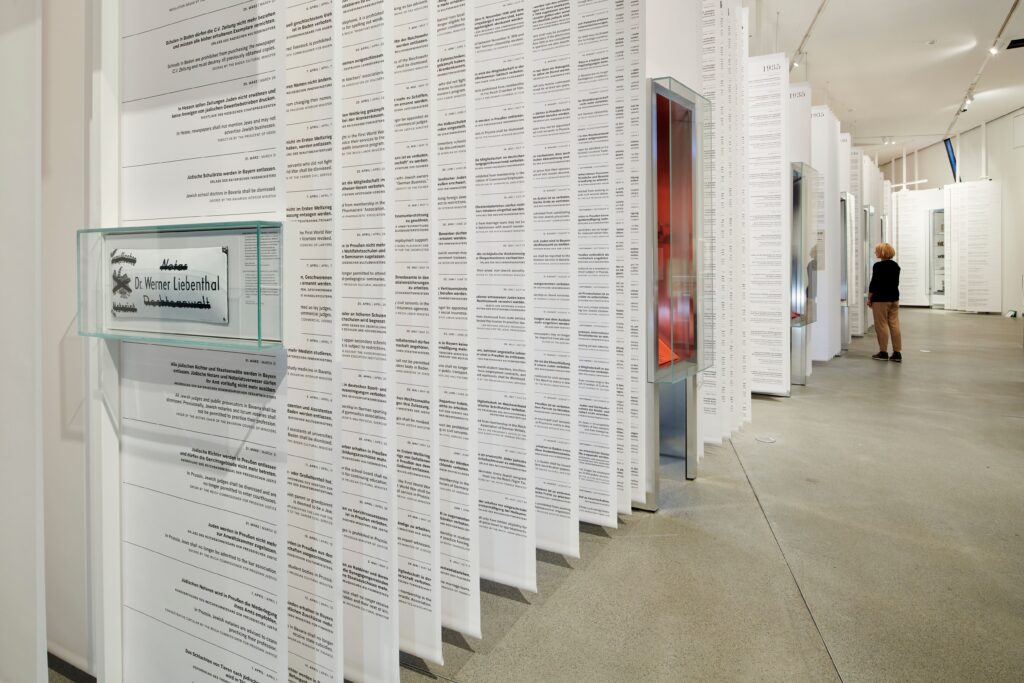

Retained from the previous exhibit are the famed voids—empty spaces that Libeskind, the architect, created throughout the building—to express the losses of the Holocaust, and the “Axes” displays on the lower level (“Axis of Exile,” “Axis of the Holocaust” and “Axis of Continuity”) that include personal stories from German Jews in the early 20th century. The new core carves out additional significant space to cover the Nazi years. One display is surrounded by a thicket of moveable screens printed with the nearly 1,000 anti-Jewish laws enacted in the period from 1933 to 1945. There are almost too many to read at one time, but their sheer volume conveys their import and impact.

The section “After 1945” covers restitution and reparations and Germany’s relationship with Israel. It also highlights the immigration of Russian Jews after German unification in 1990, Jews who today comprise the majority of the German Jewish community’s 100,000 official members.

The exhibit closes with an extraordinary video installation by Israeli filmmaker Yael Reuveny. Called Mesubin (The Gathered), it includes 55 video portraits of Jews of different ages and backgrounds talking about their Jewish identity. The impression is of being in conversation with Jews from across modern Germany.

The Torah scroll near the exhibit’s conclusion is set at the center of a jewel-like display of finely crafted ritual objects. Beautiful as they are, these items are not necessary to Jewish practice, said Friedlander, noting that “you can use any plate, any cup” to carry out the rituals.

“I am kind of shooting myself in the foot as a curator of Judaica to say none of this is important,” she said with a laugh. “But in Judaism, it’s not about the object. It’s about the ideas and words and the doing.”

Nevertheless, she knows that without the objects, there would be no message, no story and no museum.

It comes down to hiddur mitzvah, beautifying the commandments, essential to Jewish practice, Friedlander concluded:

“If you are going to do it, make it as beautiful as possible.”

Toby Axelrod is a New York-born journalist living in Berlin.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply