American View

Feature

Letter from Atlanta: Big Draw, Fading Drawl

Atlanta is the new frontier for young Jews looking for jobs, low cost of living, a progressive civic society and a full-service Jewish community.

If you meet a Jewish Atlantan these days, you may be greeted by a Northern “Hey, you guys” or a Russian “Preevyet” instead of the classic “Shalom, y’all.”

That’s because 80 percent of Atlanta’s rapidly expanding Jewish population comes from somewhere else. Although most hail from New York and New Jersey—and they are a driving force in the community’s growth over the past 10 years—there are also Jews from Israel, Iran, South Africa and the Former Soviet Union. The community has changed dramatically since German Jewish immigrants began arriving in 1845 to set up shop.

According to the 2006 survey by the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta (www.shalom atlanta.org), the Jewish community saw a 56-percent increase over the past 10 years, from 77,000 to 120,000. The areas of greatest Jewish settlement, some up to 60 miles from the city, were not even on the federation’s radar screen a decade ago, said Shira Ledman, chief planning officer of the Atlanta federation, which covers 2,500 square miles, an area larger than Delaware.

Historically, jewish life was found within Atlanta’s city limits, before shifting northward some 20 miles to Dunwoody, where the majority of the Jewish communal services are located today. Other Jewish concentrations are in Cobb County and Sandy Springs.

“They just keep coming,” said Ledman.

Depending on whom you ask, the influx was triggered by mild temperatures or the acclaim Atlanta received when it hosted the 1996 Summer Olympics and the 1994 and 2000 Super Bowls. As a result of the city’s commercial development, Atlanta has become an international magnet; Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is the world’s busiest. And the city has left behind the racial and ethnic tensions of the early- and mid-20th century to become one with a progressive civil rights record.

Who are these Jewish newcomers?

They are mostly young and affluent, drawn to a cosmopolitan business destination—think CNN, Coca-Cola and the Jewish-founded Home Depot, for starters—with relatively low living costs. The city boasts America’s third-largest concentration of Fortune 500 companies. Many find jobs in real estate, medicine and service industries.

The best indication that the nearly 5,000 resident Israelis have made a mark is the number of Israeli companies with United States or regional headquarters here: 45. Tom Glaser, president of the American-Israel Chamber of Commerce, said Atlanta ranks in the top five centers in North America for Israeli businesses; most specialize in telecommunications, medical technology and security. The largest, Amdocs Inc., is a software company and employs 700 workers.

“Israeli companies and people here are playing a bigger role overall,” noted Glaser.

Jennifer Flax, 38, and her husband, David, 37, moved from Long Island to Atlanta nine years ago so David, who recruits accountants, could begin his business. Based on recommendations, they considered Dunwoody and Alpharetta, settling on the latter. “Business was booming at the time,” Jennifer Flax said. “You can’t buy a [large] house like this in New York.”

While she misses the easy access to New York theater, Flax says she would never go back. “As small as the Jewish community is [compared to New York], it feels so large,” she said. “You have to try a little harder to be…a part of [it].” They joined Conservative Gesher L’Torah Synagogue.

There are two major Jewish cultural centers: The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum (www.thebreman.org), housed at the federation’s main downtown location, and the Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta in Dun-woody (www.atlantajcc.org). About 40,000 visitors a year tour the Breman’s Holocaust center and galleries, exhibits and archives, focused mainly on the Jewish experience in Georgia. A current exhibit details Atlanta Jewry’s darkest moment—the 1915 lynching of Leo Frank, which led to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the Anti-Defamation League (see story, page 36).

MJCCA’s annual book festival is a premier literary event in the South. This year’s festival, November 8 to 22, includes Tony Curtis, Rabbi Joseph Telushkin and CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin. The center houses two exhibition galleries, a children’s museum and a new theater.

Armed with unique cultures, beliefs and foods, some of Atlanta’s Jewish newcomers have built their own social clubs, shuls, even neighborhoods. The majority of South Africans, for instance, live in Sandy Springs, 30 miles northeast of Atlanta; they attend both Congregation Beth Tefillah, a Chabad synagogue, and Conservative Congregation B’nai Torah, which has 600 members.

Sandy Springs’ new Chabad Israeli Center draws about 165 Israelis to its Shabbat services, said Rabbi Mendy Gurary, adding that elsewhere “they don’t see many Israelis,” and the center gives them a place to speak in Hebrew and discuss Israeli politics and culture.

Also, maintaining their distinct culture are about 1,000 Iranian Jews, who live in the Orthodox enclave of Toco Hills, five miles northeast of downtown Atlanta. Congregation Netzach Yisrael conducts services entirely in Hebrew and Farsi; the older Congregation Ner Hamizrach, also founded by Iranian Jews, has a diverse membership. Somewhat ironically, residents of Toco Hills, Atlanta’s best-defined Jewish neighborhood with its yeshivot, Judaica shop and kosher grocery, live on streets with such names as Christmas, Merry and Holly.

Jews are continuing their sprawl into still-developing suburbs, popping up in remote cities such as Acworth and Norcross, where Bukharian Jews are creating a self-contained neighborhood. The King David Community Center serves about 160 Bukharian families, mostly low income, offering child care and senior programs as well as classes in Hebrew, music and dance. Founder and president Anatoliy Iskhakov noted that the center is in the midst of a campaign to erect a shul closer to where its members live as well as buy land nearby to construct more homes for them. “Now they have to walk 45 to 50 minutes from where they live to the synagogue,” he said.

A stretch of Holcombe Bridge and Spalding Roads in Alpharetta, in an area dubbed Little Russia—a mini-version of Little Odessa in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn—has a string of Russian businesses, groceries and restaurants. Some restaurants serving Russian fare bear Italian names—Verdi and Amore, for example—in an apparent effort to attract a broader clientele.

“When I came and opened my business in 2003, there were only about five Russian businesses,” said Dimitriy Goroshin, publisher ofRussian Town, a regional monthly magazine. “Now there are 9 or 10.”

Craving shawarma or falafel? There are Israeli restaurants and pita eateries in Dunwoody as well as an abundance of dairy and meat cafés, restaurants and sushi bars in Toco Hills.

“It’s a proven benchmark to evaluate the success of a community: If restaurants do well, it’s a viable and vibrant Jewish community,” said Rabbi Yossi New, Beth Tefillah’s rabbi and director of Chabad of Georgia. “You can now buy pizza on Saturday night and have a Jewish social life and have your educational needs [met] in Atlanta.”

Though only 9 percent of Atlanta Jews identify as Orthodox, that is up from 3 percent in 1996. Conservative Jews make up 26 percent, while at 46 percent, nearly half of all affiliated Jews are Reform. And all their schools are bursting at the seams.

The Davis Academy in Dunwoody, with 700 students, is one of the country’s largest Reform day schools, and the Conservative Epstein School in Sandy Springs has 650 students and is expanding. The modern Orthodox Greenfield Hebrew Academy of Atlanta has 426 students.

Atlanta is also a hotspot for singles, who make up 21 percent of the Jewish population. The annual Matzo Ball held on Christmas Eve attracted 4,300 young adults last year.

About one-third of the students at Emory University are Jewish, said Michael Rabkin, the school’s Hillel director. Alpha Epsilon Pi, the Jewish fraternity, is the largest fraternity on campus. Emory’s Jewish studies program offers 15 courses each semester.

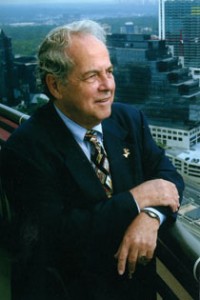

You can’t talk about the Jewish experience without mentioning Sam Massell, Atlanta’s first and only Jewish mayor, who served in the early 1970s. The dispersion of Jews throughout Atlanta today, Massell said, “is a compliment to the metro area that they are well-received here, comfortable in community life…and very much part of the fabric of Atlanta’s success.”

Massell’s father and uncles founded Massell Realty, credited for much of the city skyline. High-rise and mid-rise buildings of modern and post-modern vintage line the renowned Peachtree Street and its branches.

Continuing the Massell legacy, Sam Massell was in real estate for 20 years, as was a cousin, Steve Selig, a prominent developer, former federation president and United Jewish Communities national campaign chair. “It’s not surprising to me that Atlanta’s Jewish community is growing, because Atlanta is growing,” Selig said.

Massell, president of the Buckhead Coalition, a nonprofit chamber of commerce, is now considered the unofficial mayor of Buckhead. One of the nation’s wealthiest communities, Buckhead is home to the city’s oldest and largest Conservative synagogue, Congregation Ahavath Achim, dating back to 1887. Not far away, along Peachtree Street, is The Temple; the neo-Classical structure is Atlanta’s oldest synagogue. Founded by German immigrants in 1867, the Reform Hebrew Benevolent Congregation is a national historic site. It gained national attention in 1958 when a white supremacist bombed it.

Around that time, most Atlanta Jews lived in such places as Druid Hills, where Massell grew up on Ponce de Leon Avenue. (For a glimpse of this area and the lives of Atlanta’s well-to-do in the 1950s, check out the 1989 Oscar-winning movie, Driving Miss Daisy.)

Native Atlantan Diane Bernstein, 69, often feels like the last of her kind. “It’s a whole different community,” observed the Sandy Springs resident. “When I grew up, I cannot say we all knew each other, but we had heard of each other…. When I grew up, it was a small, mostly Christian city. Now I feel very secure that the Jewish community is a factor [here].”

Despite the city’s transformation, Atlantans are still “the personification of warmth and Southern hospitality,” said Paula Zucker, director of Greater Atlanta Hadassah. With over 2,800 members, Atlanta’s chapter has been recognized for its growth potential as a national Hadassah grant recipient.

“Atlanta, despite growing so fast, still has a very friendly reputation,” Zucker said. “Even transplants like myself…reach out to people when they come here. ‘Shalom y’all’ still works, and some say it with a New York accent. But you know what? It’s still Southern.”

Roni Robbins is a freelance writer living in Atlanta.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply