Israeli Scene

Feature

Israeli Innovation at Work in Groundbreaking Burials

Dramatic changes are taking place in the Judean Hills near Jerusalem’s entrance. A huge cemetery that has long been the first sight to greet drivers approaching the city on the windy highway from the central plains is undergoing massive expansion.

In recent years, faced with increasingly scarce land on which to expand, authorities at the Har Hamenuchot burial complex—mount of rest, in Hebrew—have been transforming the landscape both above and below ground. It’s all part of an array of extraordinary solutions that a few major urban cemeteries across Israel are adopting to accommodate the dead.

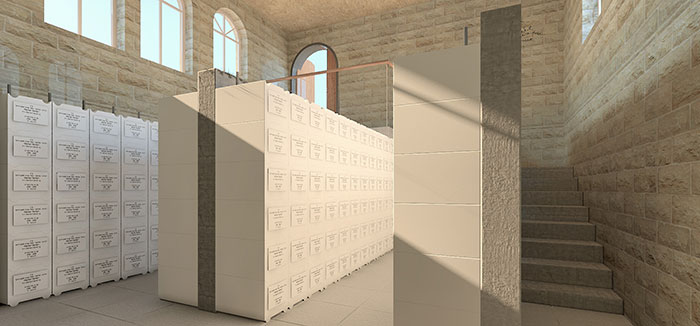

They have built upward, creating multilevel towers that resemble parking garages—except that instead of cars, graves cover the floors and are built into the walls. In some cases, the square-holed horizontal slots that serve as in-wall resting places begin at the floor and rise in rows above eye level. Meanwhile, extra-deep holes are being dug in the ground so spouses can be buried in a single grave, one on top of the other.

The latest innovation at Har Hamenuchot, the city’s largest cemetery, is the most groundbreaking, literally: the creation of massive underground catacombs where Jews are buried in the floors and walls of subterranean tunnels. With 23,000 coffin-sized hollows planned, the cavernous tunnels resemble a gigantic morgue, but the cavities in the wall are meant as eternal resting places.

Not everyone is happy about the cemetery’s enlargement.

“Every time I return to Jerusalem, I see the cemetery at Har Hamenuchot growing and growing, sprawling over more hilltops, with floors upon floors of tombstones and lots of concrete,” says Ayelet Cassel-Kraus, an urban planner with the Jerusalem-based firm Street Smart. “It’s an eyesore.”

In a country with a birthrate higher than that of any Western nation and a population density akin to Rhode Island—the second most densely populated state after New Jersey—Israel faces an increasingly dire problem of congestion. Roads are choked with traffic, residential skyscrapers are blanketing the landscape, and the health care system is straining under the weight of Israel’s burgeoning population, now at 9 million.

Some 45,000 Israelis of all faiths die per year, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

“Land shortage is one of the biggest problems of this country, and we barely pay attention to it,” says Rabbi Rafi Ostroff, head of the religious council and burial society, or chevra kadisha, in Gush Etzion, a large West Bank settlement bloc just south of Jerusalem. “The crisis is already here. There are 7 million Jews in the state today. So we’ll need 7 million graves in another 100 years, and 3.5 million in the next 50 years. There’s no room for 3.5 million graves.”

The new burial methods in use in Jewish cemeteries haven’t yet spread to Israel’s 2.3 million non-Jewish citizens, most of whom are Muslims who live in the Galilee and Negev, where there’s more open land.

Israel has about 800 active Jewish cemeteries. In Tel Aviv, the country’s largest metropolitan area, cemeteries reached maximum capacity for traditional in-ground burial three decades ago. Today, residents there are served by the Yarkon Cemetery in Petach Tikvah, the country’s largest burial ground. It features approximately 110,000 traditional gravesites and relatively new vertical, above-ground structures resembling apartment buildings that add approximately 250,000 spots.

Ostroff and Cassel-Kraus are among a small group of activists—including architects, a few rabbis, urban planners and academic scholars—proposing a solution they say is more sustainable, cost-effective and environmentally friendly than the methods being adopted at Israel’s most crowded cemeteries.

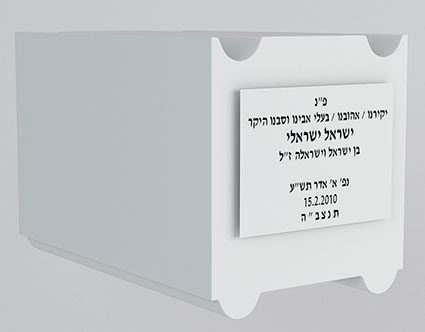

What’s more, they say, their solution isn’t new, but a revival of a talmudic-era burial method once commonly used in the Land of Israel: ossuaries.

Here’s the idea: When a Jew dies, he or she would be interred in the earth at a local cemetery. As is typical in Israel, the deceased would be buried in a shroud (coffins are used in Israel only in military burials and other limited instances where the body may no longer be intact). After a year or so, once the body has decomposed, the bones would be dug up and transferred to an ossuary, a small chest of the kind once widely used during the Second Temple period. The ossuary would be placed in an onsite tomb that could hold hundreds of ossuaries, with the bones of family members grouped together. The area needed for the temporary in-ground burial would be relatively small.

If more space is needed for the tombs, then after several decades, once loved ones presumably have ceased to visit, the ossuaries could be relocated to somewhere in Israel’s periphery, where land is relatively abundant.

“We’re proposing a solution that is halachic, traditional, cost effective and environmentally sustainable,” says Yair Furstenberg, a professor of Talmud at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who is among those spearheading the initiative known as Land of Israel Burial or bone collection. “It’s possible to think more flexibly about burial methods. I believe that if the state doesn’t advance this, secular Israelis increasingly will choose cremation.” (Cremation, which is halachically prohibited for Jews, is relatively uncommon in Israel.)

“When people see the unsightly new burial methods,” Furstenberg says, referencing the vertical necropolises, “our ideas gain legitimacy. The rabbis need to understand that this is a good public option.”

Numbers make the strongest argument for this burial method, say proponents. Traditional cemeteries can fit about 1,200 bodies per acre. With multilevel burial, about 10,500 bodies can be interred per acre, albeit at a greater cost due to construction expenses.

The new catacombs beneath the Har Hamenuchot cemetery in Jerusalem can hold up to 6,000 bodies per acre, but cost $77 million to build. Burials have already begun in the first section and construction is ongoing. Hailed as the world’s first underground cemetery, the catacombs feature multiple tunnels several stories high with burial slots carved into the walls and ground. The tunnels are brightly lit, air-conditioned and lined with Jerusalem stone, and elevators bring visitors to graves as deep as 160 feet underground.

Large reddish orbs designed by a German artist serve as ner tamids—the permanent light that’s a fixture in synagogues. The area is wheelchair accessible and airy, with balconies overlooking multiple levels of graves. While some visitors might find the experience eerie, one major advantage of the layout is that funeral-goers are protected from the harsh Jerusalem sun, which not infrequently is blamed for fainting during funerals.

An ossuary tomb can hold about 14,000 remains per acre: 348 ossuaries per tomb, with 40 tombs per acre, according to the calculations of Elisha Mor, an architect in Haifa who has designed several cemeteries.

“With today’s population in Israel, we can’t continue at this rate. All the open areas will turn into one big cemetery,” says Mor. “The ossuary method doesn’t require much land because the bodies are interred in the earth just for a year. It’s also very inexpensive. It reduces the cost of land and construction.”

Mor estimates costs at about $200 to $300 per burial, excluding labor for bone collection and possible transfer of the ossuary to another location decades down the line.

The issue of cost is a national concern, because every Israeli has a right to be buried relatively close to their home for free, on the government’s dime. National Security, akin to social security in the United States, pays the funeral costs—including the burial plot, transport of the deceased to the cemetery, ritual cleansing of the body, the shrouds, the burial itself and the erection of a temporary grave marker. The government spends about $80 million per year on burials.

The burial societies that run the country’s public cemeteries make ends meet with a combination of government funding and fees from Israelis who wish to choose their own burial plots rather than accept whatever is assigned to them—often to ensure they’re buried with loved ones.

When Hagit Shamli lost her 77-year-old father, David Shamli, after a stroke last December, family members had to make a quick decision. The burial society in Rishon LeZion, the city south of Tel Aviv where her father lived, presented the options. Only one was free: wall burial.

At the funeral, many of the mourners were taken aback, she recalls.

“When they slide you in, almost like into a pizza oven, it’s a little unpleasant,” Shamli says. “I had never been to a funeral with wall burial before. It’s quite shocking.”

Jacob Burgida of Englewood, N.J., flew to Israel last year after the sudden death of his 55-year-old sister, Rifka Kaufman of Jerusalem. When he arrived, hospital social workers explained to him that his sister had a right to free burial at Har Hamenuchot. But it wasn’t until Burgida arrived at the funeral that he realized she’d be buried in a wall in the vertical space.

“The whole thing was very odd and uncomfortable and strange,” Burgida says. “They slid her in on a gurney and put in a little dirt; that was it.”

Despite his discomfort, Burgida says he understands the reasoning behind it. “Do I appreciate the fact that Israel was able to do it for free? Yes, it was very helpful, because it can be very expensive, as I know from here in the States.”

Israeli cemeteries also generate income from Diaspora Jews who pay to be buried in Israel. Costs for foreigners vary by cemetery, depending on location. A plot at Eretz HaChaim cemetery near Beit Shemesh, about 20 minutes outside Jerusalem, costs $9,500. On the highly coveted Mount of Olives, where prophecy says the dead will be resurrected when the messiah arrives, plots can cost up to $30,000. There are additional fees for transport of the deceased, permits and other incidentals.

Rachel Kolski, director of Land, Water and Public Institutions in Israel’s Planning Administration, a unit of the Israeli Finance Ministry, agrees that more burial solutions are needed. “An area that has graves can’t undergo urban renewal like we do with residential areas, changing low-density housing to high-density skyscrapers. It will be a cemetery forever.”

Not too long ago, Kolski notes, many Israelis considered multiperson graves, multilevel cemeteries or burying the dead in walls repulsive. But today they’re all happening because this is how the government decided to address the problem of overcrowding. Israelis who want to avail themselves of no-cost burials must accept it, she says.

Given these new methods, the proponents of ossuaries say that their burial plan should be an option, too.

But in order for bone collection to become a reality, several hurdles would have to be overcome—first and foremost among Israel’s religious establishment. Burial societies are required by law to adhere to halacha as defined by Israel’s Chief Rabbinate, which hasn’t taken an official position on the ossuaries. But the Religious Services Ministry, which controls licenses for burial societies, contends that ossuaries contravene halacha.

“The idea is ludicrous, grotesque and unworkable,” as well as not halachic, says Avraham Rozen, spokesman for the Religious Services Ministry, which denounced a one-day conference on the subject at the Israel Planning Administration in Jerusalem in January. “The subject is off the table.

“All the great sages in Israel are against the idea of bone collection,” he continues. “Even in the time of the Mishnah, it was used only sporadically and on an individual basis.”

Not so, say Ostroff and Furstenberg, who cite mishnaic texts and archeological evidence from the first and second centuries to argue that ossuaries were the dominant form of burial in the mishnaic period.

They ascribe the ministry’s opposition to political considerations and reflexive resistance to change by its haredi leadership.

Another obstacle is the Israeli Health Ministry’s current ban on disinterring bodies; that regulation would need to change.

And, of course, the Israeli public would have to embrace the concept. Proponents say they don’t want to force ossuaries on an unwilling populace. Rather, they want to introduce the idea as a viable choice. The government could help by passing legislation requiring religious authorities to allow this low-cost, low-land-use method and offering financial incentives to promote it.

“The goal is to create more burial options, not to compel people to use this method or another,” says Cassel-Kraus, the urban planner. “We want to offer a diversity of halachic options and for people to willingly choose this.”

Despite the many obstacles, Mor says he’s confident that ossuary burial will become a reality. “The state should be thinking of land use for the living and not for the dead.”

Uriel Heilman is a journalist for JTA–The Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Tuvia (Gary) Lavit says

Please contact me. I want to be buried in an OSSUARY as outlined in this article. I am 77 years old and want to make this arrangement as soon as possible. I would not want to be buried forever in one of those above-ground, file-cabinet-like holes in that vertical wall on Har Hamenukhot.

Russell Donnelly says

First of all,were I to have a little accident in Israel while biking there,as per my license,they take whatever is useful from my body-corneas,kidneys,maybe liver,maybe heart valves,bone ligament grafts,whatever.who cares?then,i am not opposed to this ossuary gimmick.But,as someone far from dati I would prefer the Recompose method.don’t waste space and money on a concrete box:let my relatives visit my forest.