Books

Feature

Picking Sabras

Once, every kibbutz had an old-timer who cultivated a cactus garden, and anyone who happened to be passing by was taken forcibly by the hand to this cactus garden to see cacti and hear stories about cacti and was even expected to enthuse over the grafting of cacti into all sorts of prickly monster shapes.

Once, every kibbutz had an old-timer who cultivated a cactus garden, and anyone who happened to be passing by was taken forcibly by the hand to this cactus garden to see cacti and hear stories about cacti and was even expected to enthuse over the grafting of cacti into all sorts of prickly monster shapes.

Regrettably, I am not that interested in cacti, but I do have one of my own, a cactus I am very fond of—a large sabra prickly pear that rises up at the rear of the garden. I did not plant it, nor do I look after it. From time to time I cut and remove creepers attempting to climb up its trunk to reach sun and light. Aside from that, I don’t need to bother with it at all. It’s a large, ancient creature, strong and independent, that survives in all conditions and overcomes all hardships. It does not need watering, either, since it hoards water in its succulent stems, and one is best advised not to touch it at all.

I do not know who planted this sabra. Perhaps the Arab tenants who lived in the area before it was purchased from its owner—a rich Arab who lived in Beirut—by Germans who established a village on it? Perhaps the Germans themselves, who decided to assimilate into the area? Or someone from the Israeli collective moshav that was established here after World War II, when the British expelled the Germans back over the seas? The sabra does not answer any of these questions but simply stands there, and every summer it blossoms and produces fruit that is good enough for me to eat.

Anyone hiking in Israel knows there are many sabra bushes like these, all looking as though they were sown by God in the middle of nowhere. Almost always, this nowhere was once an Arab village, but ironically the word “sabra” is a Zionist nickname for Jewish children who were born and raised here even before the establishment of the State of Israel, as is written in Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s capacious dictionary: “A nickname for children raised in the Land of Israel who did not learn European manners.” This can be understood in a positive light—a Hebrew child free of Diasporic complexes. And also in a negative light—an insolent and impolite Hebrew child.

Anyone hiking in Israel knows there are many sabra bushes like these, all looking as though they were sown by God in the middle of nowhere. Almost always, this nowhere was once an Arab village, but ironically the word “sabra” is a Zionist nickname for Jewish children who were born and raised here even before the establishment of the State of Israel, as is written in Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s capacious dictionary: “A nickname for children raised in the Land of Israel who did not learn European manners.” This can be understood in a positive light—a Hebrew child free of Diasporic complexes. And also in a negative light—an insolent and impolite Hebrew child.

There are varying claims as to the ownership of this innovative term, and I won’t go into detail here. I will only say that it is customary to give the rather schmaltzy explanation that Israeli children are like the fruit of the sabra: prickly on the outside but soft and sweet on the inside. But the real reason, so I believe, goes a little deeper than this, namely that these bushes seemed to embody the essence of locality to new Jewish immigrants.

In spite of its successful branding, the sabra itself is not a sabra, born in Israel, but an immigrant. It is native Mexican, brought to Europe by the Spanish at the beginning of the 16th century. And because it acclimatized easily, and its fruit is so tasty, and its trunk can become an impassable obstacle, and also because it’s a hardy plant that makes do with the bare minimum—it was joyfully adopted throughout the Mediterranean Basin, including Israel. While traveling, I have come across it in Sicily and Spain and Sardinia and France and Greece and Italy. I greet it each time the way one greets a relative or an acquaintance, and for a moment I feel at home.

In my Jerusalem childhood, I picked sabras in Lifta, Sheikh Badr and on the western extension of Mount Herzl, also a former Arab village that has meanwhile been taken over by Yad Vashem. In my Nahalal childhood, I picked sabras at Ein Bedah, close to the Ramat David Air Base. The truth is I should have written “we picked,” the plural, because we were always together, a barefoot troop of children, venturing out to pick sabras, like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

How does one pick them? Well, back then we would arm ourselves with a long stick to which an empty tin can was nailed at one end, wobbling like the milk tooth of a six-year-old. We chose fruit that was golden green—the ruddier colors are overripe—stretched the stick toward the fruit, inserted the tin can over it, tilted it, pulled, and if the can did not break loose and the fruit didn’t fall, it was ours, complete with the minuscule, loathsome spines that quickly detach from the fruit and stick in your skin.

Today, a tin instrument made for this purpose can be purchased in any hardware store in the Arab villages of northern Israel. One side fits small sabras, and the other side fits large ones. And there is another method: Put a sturdy work glove on your hand, the cheapest and simplest type, grasp the fruit, and pick it. While picking sabra with a stick or a glove, or any other method of picking, it is recommended to wear a long-sleeved shirt and to consider the direction in which the wind is blowing, because the spines break away and fly off, and to realize that all this will be in vain, that sabras are procured through suffering, although beyond their spines awaits the sweetness of the fruit.

You pick, you get pricked, you roll the harvested sabras on the ground, you get pricked some more, you strike them lightly with pine branches, drop them in a pail, go home and try to remember not to wipe the sweat from your face, because that will become covered with spines, too. At home, wash the fruit under running water and then peel: With a sharp knife remove both ends of the fruit, make a cut from its North to South Pole, grasp either edge of the incision, get pricked again and pull apart. If it is sliced correctly, the fruit will peel with the ease of a man removing his coat.

Now is the time for all sorts of people to arrive, asking for a taste. You might grumble: “Pick them yourself,” but it is nicer to feed whoever is hungry, even if they are parasites who did not work hard, who did not pick or clean or get pricked. In any case, the sabras must be chilled before eating. Place them in the refrigerator and meanwhile ask a close friend, preferably the Dulcinea for whom you went out to pick sabras in the first place, to equip herself with a pair of tweezers in order to nitpick the spines from your skin.

And so, while the peeled sabras are cooling, stretch out on the cold floor and cool yourself as well, and while your beloved is attending to your wounds, rest on your laurels: Here you are, the manliest among men, out hunting the most dangerous creatures in nature. Solo, with only a stick in hand, facing a gang of bandits armed with ten thousand minuscule burning spears and thousands of invisible daggers.

Dear men, hear my voice; suitors and lovers, give ear to the words of my mouth: Pick sabras for your loved ones, as I did for mine. The sabra is a vegetarian dish, organic, valiant and manly, yet not crude or violent, nor chauvinistic. Pick sabras, peel them, place them in the refrigerator, and in the heat of the day welcome your loved ones with this oh-so-sweet chilled delight. Enough of “I squeezed you a glass of wheatgrass, my dove.” From henceforth say: “I picked you a sabra. Do you want it?”

And you, dear lady reader, even if that very day you went to the supermarket and bought a cellophane-wrapped tray of sterile, tasteless sabras, polite ones devoid of spines from the outset, wrap your arms around your Ulysses and draw him toward you—just as at the end of the book of the same name—drawn to your perfume and your breasts, and his heart will beat like mad, and you will say: “You picked sabras for me? Yes, I want them…yes I will Yes.”

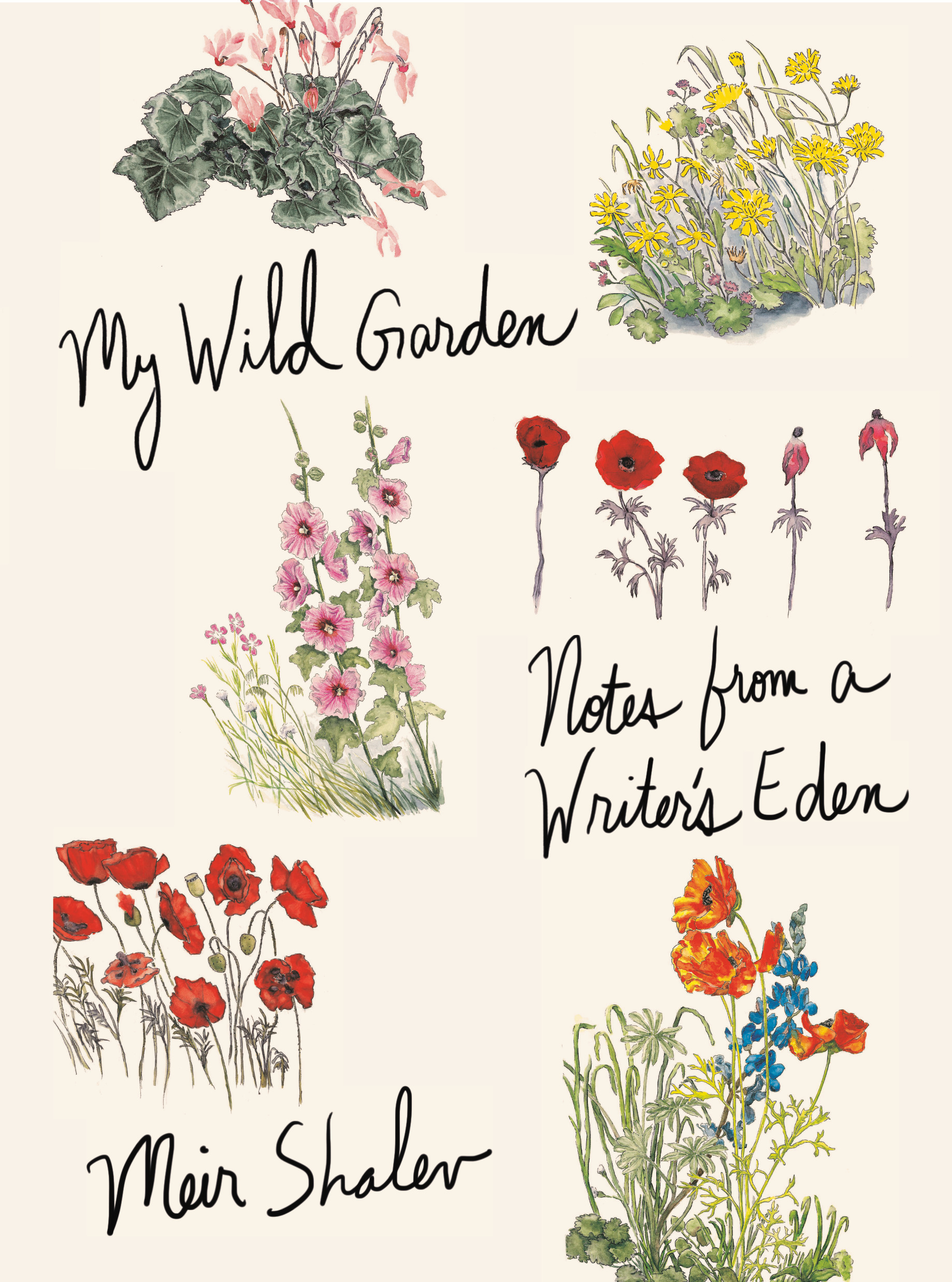

From MY WILD GARDEN by Meir Shalev, translated from the Hebrew by Joanna Chen. Copyright © 2020 by Fontanella Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Click here to purchase the book.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Kathryn Miller says

What a wonderful article. Thank you. Shalom.