Books

Fiction

Excerpt: Ribalow Prize-Winner ‘The Last Watchman of Old Cairo’

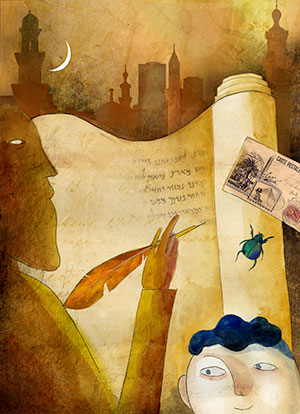

Joseph has always been puzzled by his dual heritage. Though he lives a conventional life in Santa Fe with his Egyptian-born Jewish mother and her American husband, Bill, his Muslim father, Ahmed—a constant, albeit distant, presence in his life—is a mystery to him. Father and son are connected by a Sunday night ritual of phone calls and bedtime stories, especially about the generations of men in the al-Raqb family who have been caretakers of the Ibn Ezra Synagogue in Cairo. When Joseph, at 11, finally goes to Cairo to spend the summer with his father, it is just the beginning of a journey into his father’s world and a glimpse of his family’s enduring loyalty to guarding the synagogue and its cache of artifacts. It is only years later that a grown Joseph will return to Cairo to excavate the past.

Michael David Lukas’s book, The Last Watchman of Old Cairo, 2019’s Harold U. Ribalow Prize winner, takes readers down a road of mystery and enlightenment. The following excerpt is from the second chapter.

For most of my childhood, my father occupied that sector of my imagination otherwise reserved for myths and legends. Somewhere between King Arthur and Zeus, he was that distant and usually benevolent demigod who oversaw the realm of air mail and phone calls, provider of pharaoh statues, pyramid paperweights, and, for my ninth birthday, a real Egyptian scarab. Playing catch, driving me to school, telling me to buck up when I struck out or skinned my knee—all those more prosaic paternal duties were covered by my mother or Bill. All things considered, they did a pretty good job of it. There was nothing tangible missing from my childhood. Still, I was always aware of a disjuncture, that fatherly lacuna.

I have no doubt that he tried his best, in spite of the distance. There were postcards and visits. His birthday presents always came on time and, for as long as I can remember, he called me every Sunday night just before bedtime. He would ask me about school or soccer practice. Sometimes he told a humorous anecdote he had heard from Uncle Hassan or the man who sold newspapers on the corner outside his apartment. And every week, as I settled into bed with the hard-plastic earpiece of the phone pressed between my head and the pillow, he would ask if I wanted to hear a story.

My father told stories about dragons and djinns, buried treasure, fishermen, and wayward princes. But his best stories were those drawn from our family history, stories about the long line of al-Raqb men who had, for nearly a thousand years, served as watchmen of the Ibn Ezra Synagogue. There was the story of Ahmed al-Raqb, my father’s namesake, who had faced down an angry crowd that believed the Jews were immune to the Great Plague. There was the one about Ibrahim al-Raqb, who convinced the ruthless Mamluk ruler Baybars to accept a fine in lieu of destroying the synagogue. And then, of course, there was the story of Ali al-Raqb, that first and most noble watchman, whose bravery helped to establish our family name.

I often fell asleep before the story was finished and would wake up again when my mother came in to kiss me good night. She would take the phone out of my hand and, as I drifted back to sleep, I would hear her talking to my father in the living room. These were the only times I ever heard her speak Arabic, and I remember how different she sounded then, in her native language, almost nothing like the woman who packed my lunch every morning, kissed me on the top of my head, then went off to teach French at the local community college.

For many years, this is how it was. There were birthdays and sleepovers, ski weeks and a shelf full of plastic trophies. Then, one Sunday toward the end of fifth grade, my father asked me whether I wanted to spend the summer with him in Egypt. He and my mother had already worked out all the details. I would stay with him in Cairo for two months, then come back to Santa Fe a few weeks before school began.

“It’s up to you,” my mother said the next morning at breakfast. She liked the idea. It was a great opportunity, a chance for me to spend time with my father. “I just want to be sure that you’re sure.”

“It’s a big trip,” Bill added.

I didn’t understand why there was even a question. Why wouldn’t I want to spend the summer with my father in Egypt?

“I’m sure,” I said, looking up from my Raisin Bran. “I’m sure I’m sure.”

And so it was settled.

There must have been more conversations, discussions of what to pack and whether it was a good idea to drink the water in Cairo, a trip to the travel doctor. But I don’t remember any of that.

Read our Q&A with Michael David Lukas, author of The Last Watchman of Old Cairo, here.

What I do remember, distinctly, is stepping onto the tarmac in Cairo, my little red-and-black-plaid suitcase in one hand and a blank customs form in the other. My father was waiting for me just past border control, leaning against a white pole and smoking a cigarette. He wore an old gray suit jacket, and I remember thinking that his mustache looked like a small aquatic mammal, a river otter maybe, or a ferret. I saw him before he saw me, and for a moment I just stood there, watching him smoke. My father. I repeated the phrase a few times under my breath, trying it on for size. Then I took a step forward and he spotted me.

“You are here,” he said, and when he leaned over to embrace me, my head spun with that potent Levantine potpourri of cigarette smoke, cologne, and stale sweat. “Welcome, my son.”

On the taxi ride back from the airport he was excited, rustling my hair and talking in his broken shuffle of English about our plans for the summer. I tried to pay attention to what he was saying, but I was tired from the flight and spent most of the ride staring out at the city, at the piles of trash and the crumbling unfinished apartment buildings, the freeway overpasses crammed with honking little taxis and the bright Arabic billboards advertising strange brands of laundry detergent and fruit juice. “Here we are,” my father said proudly as the taxi pulled up in front of a huge cement apartment block. “What do you think?” It wasn’t how I imagined. None of it was. But the last thing I wanted was for him to see the disappointment on my face. “It’s nice,” I said, doing my best to smile. “Really great.”

That first week in Cairo wasn’t easy. Stuck in a strange hot polluted city with a father and a family I hardly knew, I had a bad heat rash and persistent low-grade diarrhea, both of which were exacerbated by my Aunt Basimah’s home remedies. My father lived with his brother—Uncle Hassan—and his family, which meant I was forced to share a bedroom with Aisha. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that she was forced to share a bedroom with me. In any case, she made no secret of the inconvenience I caused by being in her space. “Do you have to breathe so loud?” she asked that first night as we lay across the room from each other. Her slight British accent gave the question an extra sharpness. I told my mother I wanted to come home early and she said to give it a few more days. As usual, she was right. Eventually I got used to the microbes and everyone calling me Yusuf. The heat and pollution began to feel normal and, by the end of that first week, Aisha and I were inseparable.

But as much as I enjoyed spending time with my cousin, the best days were those when my father agreed to take me along with him on his rounds. After lunch, we would catch a taxi to Nasr City, Dokki, or some other unfamiliar neighborhood, and walk together up the main street, drumming up business for Uncle Hassan’s burgeoning produce distribution concern. My father was a born salesman and it was a pleasure just watching him work. As he wheedled and joked, smoked cigarettes and drank glass after glass of sweet black tea, I sat quietly in the corner of the restaurant or produce stand, reading my comics and thinking about the rice pudding the two of us always shared at the end of the day. Occasionally, a friendly waiter or shopkeeper would direct the flow of conversation my way and I would respond with the string of stock Arabic phrases Aisha had taught me.

“I don’t speak Arabic well. I am American of Egyptian heritage. I like Cairo very much.”

“I don’t speak Arabic well. I am American of Egyptian heritage. I like Cairo very much.”

This was usually sufficient to slake their curiosity. And it was true. Aside from those first few weeks, it ended up being a great summer. My father and I rode camels behind the pyramids, we saw the mummies at the Egyptian Museum, and we climbed the stairs all the way to the top of the Cairo Tower, from which we could see the entire city spread out below us like a map. But of all the days that summer, the one that stuck with me most was the afternoon my father took me, Uncle Hassan, and a couple of distant male cousins on a felucca ride down the Nile.

It was a bright blue-and-white day. there was a soft breeze blowing upriver and the windows of the skyscrapers along the water glinted with reflected sunlight. I was sitting with my father at the back of the boat while Uncle Hassan and my cousins manned the front. We sailed up the Nile for an hour or so; then the captain dropped anchor near the bottom tip of Zamalek and everyone stripped down to their underwear and jumped in. They beckoned for me to join, but in spite of my father’s assurances, I didn’t trust the water. It looked like the kind of river—thick with silt the color of coffee ice cream—where you might find leeches and piranhas or, at the very least, those slimy little fish that ate the dead skin off your feet.

“No, thank you,” I said in Arabic and leaned back against the side of the boat in an effort to convey my comfort.

After a few minutes of splashing around, Uncle Hassan pulled himself back into the boat. I remember he smiled and made as if to light a cigarette. Then, with a violent lurch, he wrapped his arms around my chest and threw me into the Nile. The abruptness of it knocked the wind out of me and when I came up, sputtering and coughing, trying to tread water in wet shoes and jeans, everyone was laughing. My cousins sang a humorous song in my honor and I tried to laugh along with them, even though I knew I was the butt of the joke.

Back in the boat, I took off my wet clothes and set them out to dry. There were angry tears welling up at the corners of my eyes, but I held them back, knowing from experience that crying only made things worse. I was mad at Uncle Hassan. But most of all, I blamed my father, for allowing it to happen, for not protecting me, and for chuckling to himself as he draped the towel over my shoulders. To his credit, he didn’t say anything once he saw that I was upset. He didn’t try to explain himself or apologize. He just sat there with me at the back of the boat, watching the murky brown water pass a few feet below us.

“There is a proverb,” he said eventually. “ ‘Drink from the Nile and you will always return. Swim in it and you will never leave.’ ”

Then he leaned over the edge of the boat and cupped out a handful of water.

“This is our blood,” he went on, trickling the water onto my knee. “Nearly a thousand years our family has lived on the Nile. This river is in our veins.”

He lit a cigarette and we were both quiet for a long while.

“We are watchers,” he said, throwing the half-smoked butt into the Nile. When I didn’t respond, he explained. “Our name, al-Raqb, it means ‘the watcher,’ ‘he who watches.’ ”

“ ‘He who watches,’ ” I repeated, and he smiled.

“It is the forty-third name of God.”

He thought for a moment, shading his eyes against the sun; then he asked me the same question he asked every Sunday night.

“Would you like to hear a story?”

“Yes,” I said, and he began.

“Once there was a boy named Ali—”

I must have heard that story a dozen times before. But that particular afternoon—watching the city unfold from its haze—it felt more immediate, more real. This river a few feet below us was the same river that had flowed through the city a thousand years earlier, when Ali al-Raqb first took up the position of watchman, the same river that had flooded the valley every spring for hundreds of years.

“We protect the synagogue,” my father said when the story finished, “and we guard its secrets.”

“Secrets?” I asked.

He shifted in his seat and, glancing back over his shoulder, dropped his voice slightly, so no one else on the boat could hear what he was saying.

In one corner of the courtyard, he told me, there was a well that marked the place where the baby Moses was taken from the Nile. Beneath the paving stones of the main entrance was a storeroom filled with relics, including a plank from Noah’s Ark. And hidden in the attic, behind a secret panel, was the greatest secret of all, the Ezra Scroll.

More than two thousand years ago, he said, during the time of the prophets, there lived a fiery scribe named Ezra, who took it upon himself to produce a perfect Torah scroll, without flaw or innovation. He worked on the scroll for many years and when he was finished, he presented it to the entire community. The people assembled outside the walls of Jerusalem. And when Ezra opened the scroll, they all stood, for they knew that this was the one true version of God’s word. It was the perfect book, the perfect incarnation of God’s name, and it glowed with a magic that could heal the sick, enlighten the perplexed, or bring back the spirits of the dead.

“Have you seen it?” I asked. “Is it real?”

My father lit a new cigarette and stared into the water, as if he might find his story there.

“That’s enough for today,” he said, eventually, and I knew not to press any further.

For the rest of the ride, as we sailed back toward the 26th of July Bridge, I sat with my father at the back of the boat, looking out on the water and thinking about the heroic history of our family, about the Ezra Scroll and the generations of watchmen who protected it.

For much of my childhood, my last name—al-Raqb—had felt like a burden. I hated the questions it inspired, the taunts, and the well-meaning adults wondering where a name like that came from. I dreaded the moment when, without fail, substitute teachers would pause and glance up from the attendance sheet, apologizing in advance for their mispronunciation. It even looked strange—al-Raqb—the hyphen in the middle, the lowercase “a,” and that unpronounceable double consonant at the end. In third grade, prompted by a particularly embarrassing incident with a new teacher, I had waged a semi-protracted and nearly successful campaign to change my last name to Shemarya, like my mom, or Levy, like Bill. But that afternoon on the Nile, I wouldn’t have traded al-Raqb for anything.

I was a watcher, I told myself. He who watches.

Excerpted from The Last Watchman of Old Cairo by Michael David Lukas. Copyright © 2018 Michael David Lukas. All rights reserved. Used with permission of the author and publisher Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Ellen Tuckman says

Do you have a book discussion guide for the Last Watchman of Old Cairo?

Talia Liben Yarmush says

Unfortunately we do not.