Books

Fiction

Anne Frank and Hannah Arendt Get Graphic Novel Treatment

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation (Pantheon Graphic Library) Adapted by Ari Folman. Illustrated by David Polonsky. (Pantheon, 160 pp. $24.95)

The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth Written and illustrated by Ken Krimstein. (Bloomsbury Publishing, 240 pp. $28)

Anne Frank famously ended her diary in her early teens: She died at age 15 in Bergen-Belsen, shortly before the camp’s liberation. In contrast, Ken Krimstein’s story about Hannah Arendt selectively traces the philosopher’s route of survival—from Nazi Germany to occupied France and then to America. Both these works succeed in animating protagonists whose lives and works have been exhaustively appraised.

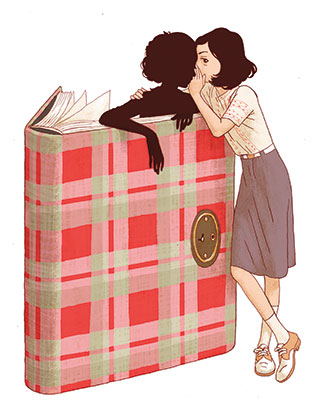

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation is a masterpiece. Writer Ari Folman and illustrator David Polonsky have produced a vibrant, sensitive portrait of the icon who hid with her parents, sister and four others for two years in the annex of the building in Amsterdam that housed her father’s business. Through text and images of seamless intelligence, Anne emerges as a wryly sophisticated, maturing young lady. Her thoughts ricochet between keen social and family observations and the horrors that are occurring mere footsteps from her hiding place. Her musings, worries and imaginings are shown in bright, sharply defined images in a range of colors, with everyday life in primary shades contrasting with the grays and browns that depict German soldiers marching prisoners in the street and planes dropping bombs.

Folman expertly balances Anne’s exterior and interior observations. While not minimizing her terrifying circumstances, he focuses more on her wisecracks than on her fears. When the van Daan family joins the Franks in the annex, Anne observes: “Mrs. van Daan looks like a diva from hell.” The accompanying illustration shows van Daan clutching her chamber pot, which she brought with her to the annex, saying, “If I must die here, I might as well be sitting on my chamber pot.”

Polonsky’s extraordinary imagination and draftsmanship propel Anne’s revered diary. Her rivalry with sister Margot is visualized in eight sets of images, each one contrasting Anne’s temper and messiness with her sister’s calm demeanor and orderliness.

This graphic novel is a valuable extension to all the literature that has emanated from Anne Frank’s diary.

Ken Krimstein’s book on Hannah Arendt memorializes a sweet moment in postwar intellectual and aesthetic history, when passionate engagement with morality was much admired. Arendt, who was born in Hanover, Germany, was obsessed with the pursuit of truth since her youth, eventually becoming a pre-eminent philosopher and political theorist and the first female full professor at Princeton University.

The earlier part of her life, however, included pogroms; a love affair with her university professor and mentor Martin Heidegger, who became a Nazi; and friends in the cultural elite—Marc Chagall, Edvard Munch, Kurt Weill, Arnold Schnabel, Bertolt Brecht, Walter Benjamin and Fritz Lang, among others. In 1933, while living in Berlin, she was arrested briefly for researching anti-Semitic propaganda for a Zionist organization. After her release, she fled to France, where she worked for Youth Aliyah. In 1940, the occupying Germans arrested her again and sent her to Gurs, an internment camp from which she ran away. After reaching Portugal, she boarded a ship to America, where she arrived in 1941.

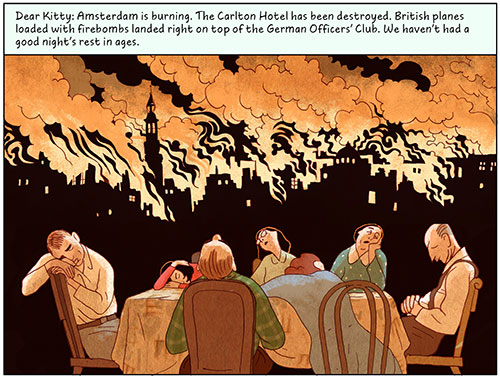

Trapped in a fascist nightmare, we watch her “three escapes,” first from Berlin, then Marseilles and the many years it took to extricate herself from the affair with her mentor. Arendt’s complicated journey—physical and existential—is depicted in wispy black-and-white drawings punctuated by dabs of green that represent Arendt. It is soon apparent that the drawings are a foil to the catastrophes in Arendt’s life.

Arendt’s worldview is shaken by the realities of the Holocaust—her cohort in Berlin believed genocide to be so inhumane that it was shelved as a dialectical impossibility. Arendt meditates on the horror: “Tradition isn’t just broken, it’s shattered. It’s had its head shaved, its soul crushed, its very existence marched into sealed chambers and exterminated. How can we still live?”

Arendt never tired of her ethical journey. Her news report in The New Yorker on the trial of Adolph Eichmann, about which she coined the phrase “the banality of evil,” alienated many friends and peers. In it, she expressed a relativist position that memory and its historical product are capricious, useless for providing a basis for an absolute truth.

Krimstein serves up an uncannily lighthearted text for such a dark, improbable subject, but the easily digestible imagery keeps the viewer racing through the story. Like Folman and Polonsky, Krimstein uses a sly magic: Readers are invited into two brightly entertaining novels, and once engrossed, the door quietly closes and traps them in stories of gravity that can’t be put down. We are held fast, fascinated and curious to both ends.

Archie Rand, an artist and muralist living in Brooklyn, N.Y., is presidential professor of art at Brooklyn College

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply