Health + Medicine

Feature

The Alzheimer’s Mystery

Wilma Clauson was nearing her 80th birthday when her family finally acknowledged that something wasn’t right. For a year or two, there had been signs that Clauson, a Philadelphia resident, was slipping. But like so many families, they chose to ignore them—after all, don’t older people often become forgetful? They made excuses when she had difficulty using the computer and the television remote, and when she stopped balancing her checkbook. They dismissed as insignificant the time she failed to show up at the restaurant where she was set to celebrate her birthday with friends. She had gone instead to her weekly Torah study class.

“But it wasn’t until my aunt died,” recalls Clauson’s daughter, Betsy Filton, “that we had to face that this wasn’t normal aging. On my way to the hospital to pick up my aunt’s things, I called my mother to tell her Aunt Reba had passed. A few hours later, I called Mom again to see how she was doing, and she asked, ‘So how is Aunt Reba?’ ”

Six years later, after being moved out of an assisted-living apartment and into a dementia unit, Clauson

died from Alzheimer’s disease; she had stopped eating because of dysphagia, the deterioration of her swallowing reflex. Her once lively intelligence and personality had vanished, leaving a silent shell of a woman. “The worst,” Filton says tearfully, “was when she stopped asking about my children. In the beginning, it’s harder for the patient. By the end, it’s harder for the family.”

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive, irreversible brain disorder that destroys memory, blunts cognitive skills and makes it hard to perform even the simplest tasks, like choosing what to wear. It’s the most common of the brain disorders lumped under the general term dementia. (Others include Lewy body dementia, frontal lobe dementia and vascular dementia.) Alzheimer’s affects 5.7 million Americans and is the sixth leading cause of death in the country. Among the elderly, it rises to number three—just behind heart disease and cancer. Two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients over 65 are women.

The disease is named for German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer, who, in 1906, was the first to see under a microscope a mass of brain tissue riddled with protein abnormalities. These proteins, later identified as amyloid plaques and tau tangles, remain the primary physiological features of the disease. They wreak havoc on the transportation system that ferries information among the neurons of the brain.

Until recently, much of the research on Alzheimer’s focused on amyloid plaques. “We had some spectacular disappointments,” says Peter Davies, Ph.D., a member of the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America’s Medical, Scientific and Memory Screening Advisory Board—AFA is part of the Coalition for Women’s Health Equity, convened by Hadassah—and director of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research’s Litwin-Zucker Center for Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders in Manhasset, N.Y. “After all the years of believing that amyloid plaques caused Alzheimer’s, we’ve finally concluded that plaque is a feature of the disease, not the reason for it. We’ve shifted to more closely examining the role of tau tangles. Personally, I am somewhat skeptical they will turn out to be causal factors, either. A lot of genetic work points to problems in the immune system, but we haven’t figured out a way to approach that.”

While scientists continue to search for Alzheimer’s cause and cure, there is a growing emphasis on prevention and treatment. “Prevention is the new treatment,” declare husband-and-wife team Drs. Dean and Ayesha Sherzai, co-directors of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program at Loma Linda University in Loma Linda, Calif. The couple’s book, The Alzheimer’s Solution, promotes a healthy lifestyle as the best option for staving off Alzheimer’s. Their mantra preaches plant-based nutrition, exercise, stress reduction, restorative sleep and optimal social and mental activity.

While these preventive ideas aren’t revolutionary, “it’s all we’ve got right now,” says Dr. Sanjeev Vaishnavi, assistant professor of clinical neurology at the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “The best we can do at this point is work on controlling risk factors—like isolation and boredom—with lifestyle interventions.” That means staying socially active and engaged with others and exercising your brain like you exercise your body. While the jury is out on whether online games like Lumosity, which purport to strengthen memory, are worthwhile, doctors do recommend challenging, cross-training mental activities such as ballroom dancing, learning a new language or mastering new musical compositions.

The focus on prevention was apparent in many of the papers delivered at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference held in July in Chicago (abstracts of the papers can be viewed at alz.org/aaic). One promising report looked at how regulating high blood pressure reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s. Several other investigators talked about the role of gut biome and the power of diet and nutrition as preventive measures.

With regard to women, the Judy Fund is taking a different path. Founded in 2004 by the family of Judy Gelfand, a beloved Los Angeles Alzheimer’s activist who died at 70 from the disease, the fund partners with the Alzheimer’s Association, which raised $332 million in 2017 and receives $2 billion in annual funding for research from the National Institutes of Health.

The Judy Fund is sponsoring an initiative that probes a possible estrogen connection to the disease. Elizabeth Gelfand Stearns, Judy Gelfand’s daughter, left an executive position at Universal Pictures to run the California-based fund. She was a producer of the Academy Award-winning film Still Alice, based on a novel about a linguistics professor diagnosed with early-onset, or familial, Alzheimer’s disease shortly after her 50th birthday. Noting that the majority of patients with Alzheimer’s are older women, Stearns says, “We need to know more about what the loss of estrogen at menopause does to the brain.”

While researchers pursue answers, there is little treatment once someone is diagnosed. By the time David Hoffman, a Philadelphia attorney, brought his then-85-year-old mother, Lenore, from her home in Florida to live with him in 2013, she had progressed to the point where she didn’t even understand what an Alzheimer’s diagnosis meant. Mostly, she was frustrated that she couldn’t answer the doctor’s questions at her evaluation. “There was nothing to do for her medically,” he says, “but I couldn’t just write her off. She’d been an avid pianist, so I would take her to the Philadelphia Orchestra, and she loved every minute of it. It didn’t matter that she forgot she’d been there. I learned to live with her in the moment and try to keep her engaged in life.”

Hoffman was right on target. The consensus today is that the most effective way for a patient to deal with Alzheimer’s is to keep busy. A study by Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals in Philadelphia recently published in JAMA Neurology found that intervening to change the behavior of people with mild cognitive impairment, which often marks the beginning stage of Alzheimer’s, makes a measurable difference. Keeping MCI designees actively involved in pursuits they enjoy, along with challenging games, slowed the cognitive decline when compared to a control group. And a program in the Netherlands is getting attention by Alzheimer’s researchers for an approach that eases the stress and anxiety of hospitalized, late-stage dementia patients. Instead of letting sufferers languish in deadening loneliness, the staff calms and nurtures them with relaxation techniques, soothing music, structured family visits and videos that simulate pleasing excursions to the beach or the mountains.

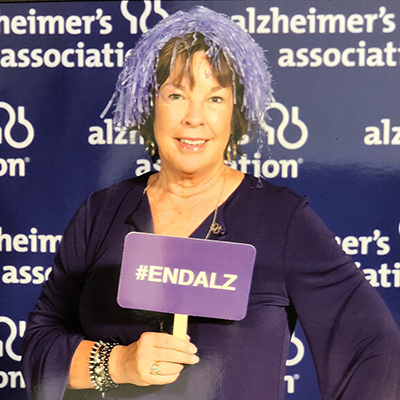

Which brings us to 63-year-old Pam Montana. When Alzheimer’s forced her to retire two years ago from her job as a sales manager at Intel in Los Angeles, she became part of the Alzheimer’s Association National Early-Stage Advisory group.

“I am determined,” she says, “to change Alzheimer’s from a disease of the dying to a disease of the living. When I got my diagnosis, I was devastated. I grieved for 24 hours, and the next day I became a fierce advocate. I announced to the world on social media that I had Alzheimer’s so I could fight the stigma of that label. I’ve raised $30,000 for research, testified before committees in Washington, spoken all over the country. I’m like Miss Alzheimer’s. It’s my way of coping.”

Montana admits she’s often frustrated: She can’t remember names, conversations or recently watched television shows. She describes her brain as feeling mushy and heavy, like plodding through a fog. She frequently has a slight headache and a ringing in her ears. But her attitude radiates surprising optimism. “I am so glad I found out early,” she says earnestly. “In a way, it was a relief. I have a chance to get my life together, to let my family know my wishes, to prioritize what I want to do in the time I have left. I’d like everyone to know that your life doesn’t have to end just because you have an irreversible diagnosis.”

Diagnosis: Alzheimer’s

To diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Sanjeev Vaishnavi of the Penn Memory Center says, “Mostly we rely on our interpretation of memory tests and behaviors. That’s why I always want the family of a new patient to be present to provide context.”

The National Institute of Aging reports that a quarter of Alzheimer’s patients have a strong family history of the disease. There is no definitive blood test, but certain gene mutations are considered risk factors. This is particularly true in cases of familial Alzheimer’s, which strikes people between the ages of 30 and 65 and represents about 10 percent of Alzheimer’s patients. There are currently four approved Alzheimer’s drugs that are administered early on—Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne and Namenda—that have limited success in temporarily slowing the disease in some patients, but they do nothing to stop the inevitable decline.

Most patients fall into the late-onset category (65 or over), which is thought to be caused by a combination of environmental, lifestyle and genetic factors, none related to Jewish ancestry, as far as researchers know.

If you have any concern about memory problems, get a free brain check by consulting the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America’s National Memory Screening Program. The website will help you find a convenient location to take a simple, one-page test to detect if you have mild cognitive impairment, which may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s. Should you score below the baseline, you’d be referred to a primary care doctor or memory center for further evaluation.

Charles Fuschillo, executive director of the AFA, is a fierce advocate of the value of testing. “Early diagnosis is critically important,” he says, “so you can get into a clinical trial, play a role in directing your life and be a part of your family planning.”

Carol Saline is a journalist, speaker and author of the photo-essay books Sisters and Mothers & Daughters.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Susan Musicant Shikora says

This article is featured in Hadassah Magazine. It would be good to know what Alzheimer’s research is being done at Hadassah, and any findings and therapies that are being utilized at HMO.

Sharon Komforty says

I really enjoyed reading this story about the Alzheimer’s Mystery. There was a lot of useful information. I am constantly reading and doing challenging puzzles, and adapting to a vegan lifestyle all in hopes of staving off Alzheimer’s. thank you for printing this story.

Patricia Rudolph says

My husband first experienced confusion and loss of memory in March of 2000 while undergoing rehab for alcoholism. Being home seemed to help him until 2006 when he gradually began experiencing Alzheimer’s symptoms. He had four to five hours a day where he wants to get a “greyhound” to “go home.” Also, he thinks I am his sister and believes he has rented a car (he hasn’t driven in five to 10 years). His personal hygiene was in the tank — it was necessary for him to change two to three times a day. Without long-term insurance for his care, it was becoming stressful to care from him. this year our family doctor introduced and started him on UineHealth Centre Neuro X Program, 6 months into treatment he improved dramatically. At the end of the full treatment course, the disease is totally under control. No case of Alzheimer’s, hallucination, forgetfulness, and other he’s strong again and able to go about daily activities. visit their official website, www. Uinehealth centre