Israeli Scene

Feature

‘The Zionist Ideas’ Reclaims Women’s Voices

When the scholar-activist Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg published The Zionist Idea in 1959, it quickly became the Zionist Bible for English speakers. For generations now, that anthology of great Zionist writings has introduced Jews and non-Jews to one of the most extraordinary mass conversations in world history. Starting in the 1880s, marginalized Jewish intellectuals in Eastern Europe, simultaneously entranced by nationalism and traumatized by anti-Semitism, debated their future. By 1948, their words, ideas and debates had produced the State of Israel, which today is home to the world’s largest Jewish community.

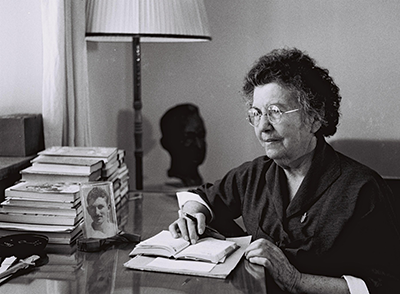

Hertzberg’s excerpts from this global discussion were so on target, so well framed, so defining, it took many of us years to realize that we were running the Zionist conversation in our heads in English, even though few of these thinkers—including Theodor Herzl, Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Ahad Ha’am—wrote in that language. Hertzberg, a prominent Conservative rabbi who passed away in 2006, enshrined a pantheon of Zionist thinkers that was so dominant, it took many of us equally long to notice his omissions. He had few voices from the right. He neglected Mizrachim. And he featured no passages from women, not even Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah.

Not including Henrietta Szold in a Zionist anthology in 1959 would be like overlooking Golda Meir when listing female prime ministers in the 1970s. With 270,000 members in the 1950s, the organization Szold had created in 1912 defined American Zionism in many ways. Already by then, with its flagship hospital about to open in Ein Kerem, Hadassah was on its way to becoming Jerusalem’s largest employer, apart from the Israeli government. Szold’s vision of Practical Zionism helped millions of American Jews reconcile their loyalty to their new Promised Land, America, with their loyalty to their people rebuilding in the old-new Promised Land, Israel. Transcending the “aliyah guilt-trips” about not moving there, Szold carved out a constructive role for American Jews as funders and builders.

Updating Hertzberg’s The Zionist Idea—a six-year project commissioned by the Jewish Publication Society, which published the original as well—gave me the opportunity to restore Szold and many other women to their proper places in the Zionist conversation. Including these women is not about being politically correct; it’s about getting it right.

In the true spirit of the now-updated and newly published title, The Zionist Ideas also opens up that conversation, enabling us to include writings from artists and activists, intellectuals and leaders that testify to the Zionist debate’s ongoing vitality. Until 1948, the Zionist idea was that the Jews are a people, with the right—like all other nations—to establish a state in their homeland, Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel. Today, we need many Zionist ideas about how to perfect that state—and how all Jews can find personal meaning from their connection to Israel. This expansion advances our understanding of what Zionism achieved, sought to achieve and still seeks to achieve.

With these added voices, we can soar with the spirit of Rachel the poet and Naomi Shemer the songwriter. We can appreciate the Americanized Zionism of Szold and Rose Halprin, Hadassah’s two-time national president who served during the establishment of the state 70 years ago. We can contemplate the multilayered relationship between Zionism and feminism in the works of American feminist writer Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Israeli historian Einat Ramon. And we can imagine confrontations across time between Israel’s left-wing firebrand Shulamit Aloni, who passed away in 2014, and Israel’s youngest-ever and current Knesset member, Stav Shaffir, on one side of the political spectrum, versus Israel’s one-time, right-wing firebrand Geula Cohen and its current daring minister of justice, Ayelet Shaked, on the other.

To read about the evolution of Hadassah’s Practical Zionism, please read Gil Troy’s accompanying story “Hadassah Zionism Shaped American Zionism.”

Zionism was empowering women long before Betty Friedan pushed feminism into the mainstream with her The Feminine Mystique in 1963. For decades before and after Israel became a state, Zionists were raised on the myth of the tough, independent and innovative chalutzah, the female pioneer pulling her weight in the fields—with the children happily raised in the kibbutz children’s house. Reinforcing the myth were female figures such as the fictional Jordana Ben Canaan, the farmer-fighter of Leon Uris’s Exodus; the Jewish-mother-turned-stateswoman Golda Meir; and every female Israeli soldier any American Jew ever encountered.

Of course, the reality was more complex. Sexism didn’t disappear despite all the Zionist—and socialist—experimentation and goodwill. And many kibbutz children felt abandoned in those communal settings. Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, a farmer, activist and First Lady of Israel’s second president, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, complained in the 1930s that “in no form of Palestinian life does the woman play her proper role economically, culturally and spiritually.” She added: “The road that lies before the women in Eretz Yisrael is still a long one, but its direction already seems to be clear.” Compared to the notion of the traditional American housewife as seen on television—obsessively cleaning and cooking à la June Cleaver in Leave It to Beaver—these pioneering women were, in fact, pioneering. “Work in the settlement was a joy,” Ben-Zvi wrote, describing the Educational Farm in Jerusalem she founded that trained city-born women to work the land. Mastering agriculture would not just make the desert bloom. It “had an additional purpose: It was a larger school of life.”

This “larger school of life” captured the Zionist revolution’s sweeping ambition. The Jews were creating a refuge for themselves after thousands of years of wandering and oppression. And the sheer acts of creating the state, tilling the soil and building homes were revolutionary. The accomplishment of state-building was impressive. As Meir would rejoice in A Land of Our Own in 1973: “If there are no more swamps in Palestine, it is because we drained them. If there are forests, it is because we planted the seedlings. If there are fewer deserts, it is because our children went to the arid areas and reclaimed them.”

But that wasn’t enough. Zionism was also about what Meir, addressing the United Nations as foreign minister on Israel’s 10th anniversary, called “acceptable nationalism,” not “national aggressiveness,” and a “nationalism which is constructive and wholesome.” And in the Zionist case, Meir exclaimed at the United Nations, “We are driven by the memory of the past, the responsibility for the future, and by the desire to live up to a sense of ‘chosenness’—not because we are better than others, but because we dream of doing better in building a society in Israel which will be a good society founded on concepts of justice and equality.” (In fact, that 1958 speech would have fit nicely in Hertzberg’s original volume.)

What Meir said in prose, others expressed in poetry and song. Zionism wasn’t just the political platforms of its founders. It wasn’t just Herzl and Jabotinsky’s Political Revolution—creating the state. It wasn’t just A.D. Gordon and Rachel Ben-Zvi’s Labor Revolution—redeeming the people by redeeming the land. It was also Ahad Ha’am and Rav Abraham Isaac Kook’s ongoing Cultural and Spiritual Revolution—reviving the national spirit in the ancestral

homeland.

In a movement dominated by larger-than-life men and women acting heroically, it took the poet, kibbutznikit and pre-state icon Rachel Bluwstein to capture the personal, smaller deeds that also created what she called “My Country” in 1926: “I have not sung you, my country,/ nor brought glory to your name/ with the great deeds of a hero/ or the spoils a battle yields./ But on the shores of the Jordan,/ my hands have planted a tree,/ and my feet have made a pathway/ through your fields.”

Naomi Shemer also mastered that graceful toggle between the personal and the political, the intimate and the monumental. Some of her songs are delightfully, achingly small. In “Chorshat HaEkaliptus,” The Eucalyptus Grove, she celebrates the intense relationship so many of us have with a particular landscape that doesn’t change from year to year, from decade to decade. In her case, the lyrics describe “the eucalyptus grove, the bridge, the boat and the scent of saltwort wafting over the waters.” In her most famous song, “Jerusalem of Gold,” written after the 1967 Six-Day War, she transforms our intense, intimate love of landscape into a people’s resounding anthem celebrating one of the greatest national redemptive projects ever. The Jewish people return to “Jerusalem of gold and of bronze and of light,” and each of us shares the same prayer, which we define individually and communally, singing fervently in unison: “Within my heart I shall treasure your song and sight.”

For all its accomplishments, 70 years after Israel’s founding, Zionism has proven to be a controversial movement—and Israel a controversial state. While we all too often feel stuck in the same pre-’48 debate justifying a Jewish state at the United Nations, on college campuses and elsewhere, the discussion has matured. Political, religious and social progress has transformed the Zionist conversation. And decades of arguments, dreams, frustrations and reality checks have intervened.

The hatred against Israel is so vicious that many feminists today who want to champion the rights of the Palestinians are willing to excuse the anti-woman violence accepted by that community as well as by Israel’s neighbors. Indeed, they ignore the egalitarianism embedded in Zionism’s DNA, and deem Zionism and feminism incompatible.

Fortunately, Zionism has had eloquent champions among feminist thinkers, like Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a founding editor of Ms. magazine, and more recently Einat Ramon, an Israeli historian. In 1982, Pogrebin became one of the first to call out feminist anti-Semitism, writing a lengthy Ms. exposé that almost ruptured the movement. In her 1991 best seller, Deborah, Golda and Me, she insisted: “Zionism is to Jews what feminism is to women. Zionism began as a national liberation movement and has become an ongoing struggle for Jewish solidarity, pride, and unity. Similarly, feminism, which began as a gender-liberation movement, has become an ongoing struggle for women’s solidarity, pride, and unity. Just as feminism has been maligned and misunderstood by those who do not bother to understand it, so, too, Zionism has been maligned and misunderstood by

its enemies.”

Decades later, still fighting surprising hostility from some corners of the feminist movement, Ramon, who writes about the early Zionist female pioneers, makes the case for what she calls “womanism” and “Zionism.” She celebrates particularism—without negating pluralism—and rejoices in the uniqueness of feminine identity and of Jewish identity. “In the same way that I long for the moment when women and men, once again, will not be ashamed to speak about their concrete female or male experiences, encouraging discussions about how to create the conditions of covenant between them,” Ramon wrote in the one essay commissioned especially for The Zionist Ideas, “I long for the moment when all Jews can again revel in their uniqueness, as we did when the State of Israel was declared.”

Today, young millennial Jewish women, harassed by anti-Zionist feminists, are refusing to accept the false choice between their Zionism and their progressivism. As Emily Shire, a politics and culture reporter for the online women’s magazine Bustle.com who in 2017 participated in Hadassah’s Defining Zionism series, proclaimed in The New York Times last year: “I see no reason why I should have to sacrifice my Zionism for the sake of my feminism.”

Part of that misunderstanding is due to anti-Semitism. But part today stems from a broader, postmodernist assault on the very notion of a particular identity itself. Many progressives, especially in universities, designate some identities, like Palestinian nationalism, as legitimate, but want Westerners—and especially Jews—to be citizens of the world. Indeed, tribalism sometimes can be brutal, xenophobic, violent. But tribalism can also be transcendent—when it helps human beings bond behind banners like liberalism, equality, freedom, democracy, feminism—and Zionism.

Clearly, there is more than one woman’s take on Zionism just as there are multiple Jewish takes on feminism. But a Zionist conversation without any women is not just a conversation barring American Zionism’s most effective organizer, Israel’s greatest songwriter or one of the world’s first female prime ministers. It’s a conversation that’s a little more sterile and a little less personal. It’s a conversation that’s less likely to characterize the deep but still restrained American Jewish bond with Israel as being “more than platonic,” and in the “blood and bones,” in the former Hadassah president Rose Halprin’s spot-on phrasing. It’s also a conversation that’s less likely to capture American Jews’ Zionist guilt, epitomized by a story that Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis, the late charismatic Orthodox revivalist, liked to tell about a sister so worried about her American-born son studying in Israel during the Yom Kippur War, she first forgot to ask about her Israeli-born nephew who was actually fighting in that war—and fell.

Clearly, there is more than one woman’s take on Zionism just as there are multiple Jewish takes on feminism. But a Zionist conversation without any women is not just a conversation barring American Zionism’s most effective organizer, Israel’s greatest songwriter or one of the world’s first female prime ministers. It’s a conversation that’s a little more sterile and a little less personal. It’s a conversation that’s less likely to characterize the deep but still restrained American Jewish bond with Israel as being “more than platonic,” and in the “blood and bones,” in the former Hadassah president Rose Halprin’s spot-on phrasing. It’s also a conversation that’s less likely to capture American Jews’ Zionist guilt, epitomized by a story that Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis, the late charismatic Orthodox revivalist, liked to tell about a sister so worried about her American-born son studying in Israel during the Yom Kippur War, she first forgot to ask about her Israeli-born nephew who was actually fighting in that war—and fell.

And it’s a conversation that misses two of the most influential, epoch-making movements Jewish women in the 20th century spearheaded: Jewish liberation in the form of Zionism and women’s liberation in the form of feminism. A conversation without women’s voices is a conversation that wouldn’t fully reflect the panoply of Zionist emotions and Zionist ideas—nor would it fully get the essence of what the Zionist movement was, and is, all about.

Gil Troy is an American presidential historian, political columnist and Zionist activist who grew up in the Young Judaea movement and made aliyah with his family in 2010. His 13th and latest book, The Zionist Ideas: Visions for the Jewish Homeland―Then, Now, Tomorrow, is the update of Arthur Hertzberg’s classic The Zionist Idea.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

daniele benatouil says

I am a French Jewish immigrant who came to the States because of antisemitism. I would love to connect with Hadassah’s team.

Danièle