Books

Non-fiction

Books: Nazism and Communism: Tracing How One Family Endured

In her seventh book, Enemies of the People: My Family’s Journey to America (Simon & Schuster, 272 pp. $26), Kati Marton provides a chilling, intimate look at the life of her journalist parents in cold war Hungary, lives that were under constant surveillance for 20 years by every employee of their household and by virtually every “friend” in Budapest.

In her seventh book, Enemies of the People: My Family’s Journey to America (Simon & Schuster, 272 pp. $26), Kati Marton provides a chilling, intimate look at the life of her journalist parents in cold war Hungary, lives that were under constant surveillance for 20 years by every employee of their household and by virtually every “friend” in Budapest.

Deftly, in clear, readable prose and without rancor, Marton uncorks a tale of suffering, bravery, survival and vindication, using the memoirs of her father and mother, Endre and Ilona Marton, her remembrances, the recollections of those who came in contact with them and, most important, the hitherto secret files compiled by the dreaded Hungarian secret police of the pre- and post-Stalinist era. It is as much a recounting of her parents’ ordeal as “enemies of the people” as a blistering indictment of government surveillance.

“Everybody in your circle, whether your parents trusted or did not trust them, was informing on them,” the head of the Hungarian state security archives told Marton when the files became available to her. That included her treacherous nanny, whom Marton despised long before she knew she was an informant, and even the family dentist, reporting on every inane, mundane, inconsequential event in the Martons’ lives. In addition, surveillance agents bugged their telephones, opened their mail and even tried to recruit them after they had settled in the United States.

“The files were full of shocks and betrayals,” Marton said in an interview in November at the Miami Book Fair. Some intimate details showed her parents to be far more complex than she thought, but helped her understand them better and intensified her love for them. As for the informers: “I have become much more forgiving and less judgmental about them. These were decent people turned into cogs of the state. These were unforgivable betrayals. But it was tough to resist. Fear is the core of a totalitarian state.”

Endre was the Budapest correspondent of the Associated Press and Ilona performed the same role for the United Press. Both wrote and spoke near-perfect English and played a keen game of bridge, which made them popular with the American legation. Both had “barely survived the Nazis” in World War II, Marton writes. Born Jewish, they became Roman Catholics. “It was a common phenomenon of the time,” Marton said in the interview. “They felt absolutely assimilated as Hungarians. They were very secular. They believed science and reason would supplant faith as the pillars of civilization.”

But that was not to be. After the war, Hungary came under the repressive Communist rule of Matyas Rakosi. The Martons were sought out by British and American diplomats who wanted a better understanding of “the Sovietization of this unfortunate corner of Central Europe,” Marton writes. “After the stigma of being Jewish in an anti-Semitic society,” they inexplicably embraced the new enemy, the Americans. “Having such powerful friends may have given my parents a sense of invulnerability,” Marton speculates. But their allegiance changed as Soviet domination descended on Budapest.

Eventually, Rakosi expelled all Western journalists, leaving the Martons as the only reliable source of information to the outside world. Because of their relationship to Western diplomats, the Rakosi government believed that the Martons were involved in espionage, and they arrested Endre in early 1955 and interrogated him endlessly. He had no information to impart. Ilona followed him to prison a few months later, taken from her home in the middle of the night in front of the eyes of her daughters. Kati was 6, her sister, Juli, 7.

Eventually, Rakosi expelled all Western journalists, leaving the Martons as the only reliable source of information to the outside world. Because of their relationship to Western diplomats, the Rakosi government believed that the Martons were involved in espionage, and they arrested Endre in early 1955 and interrogated him endlessly. He had no information to impart. Ilona followed him to prison a few months later, taken from her home in the middle of the night in front of the eyes of her daughters. Kati was 6, her sister, Juli, 7.Because their grandparents left for Australia, there were no immediate relatives to care for the girls, so they were sent to live with a friend. But when the girls were delivered to a home in another neighborhood, the friend demurred. “Where shall I send the packages for the little girls?” she asked. “So much for good friends,” Marton commented wryly. Kati and Juli were put in the care of foster parents, who received money from the Associated Press and others to care for them. During that time, the girls, bereft of their toys, friends and dog, had no knowledge of the whereabouts of their parents, and the parents had no knowledge of their girls. Endre was sentenced to six years in prison, Ilona to three.

The Martons were actually in the same prison, a few stories apart. One Christmas Eve, the authorities gave them some private time, and they “fell in love all over again,” Marton said. Her mother told her, “Prison saved our marriage.” Then, with no warning, her mother was released and her father was pardoned, probably after pressure from the West. They rejoined the girls, reclaimed their Budapest apartment and began reporting on the Hungarian Revolution of November 1956. As the revolution was being crushed by Soviet tanks, they fled to Vienna and eventually made their way to the United States.

For most people, that would be enough. Endre, now Andrew, became the State Department correspondent for the A.P. in Washington. Kati, after undergraduate and graduate degrees from George Washington University, decided to become a journalist. “There was never anything else that interested me,” she said. She joined National Public Radio in Washington as it was getting started and worked alongside and opposite her father. After three years she moved to a local television station in Philadelphia as a news writer and reporter.

From December 1977 to December 1979 she was the Bonn bureau chief for ABC News and reported from all the major European capitals and the Middle East. She married Peter Jennings and moved with him the next year to London, where he was ABC News bureau chief. While there, she read a brief item in a British newspaper that someone had just returned from Siberia and reported seeing Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Jews from Adolf Eichmann in wartime Budapest. It proved a turning point in her life.

Marton remembered that, as a child, she had asked her father whom Wallenberg Street was named after. His answer was a bit vague. Eventually, she discovered that Wallenberg was taken into custody at the end of the war by the advancing Russian army. Marton called her father in Washington and asked him to tell her everything he remembered. The result was a two-year, 10-nation quest that led to Wallenberg (Random House), published in 1982. During her research, a woman saved by Wallenberg, told Marton: “Of course, Wallenberg arrived too late to save your grandparents from the gas chambers.” It was the first time Marton became aware of her Jewish heritage. When she told her father of her “discovery,” he was cold, and it put a strain on their relationship for the next 25 years.

“I was at one point religious,” Marton said. “Catholicism was important to me. I prayed to see my parents and gave partial credit for the prayers that reunited me with them. But I was happy to discover we were of Jewish background.” She said she was “very proud” of her forefathers. She found that her great-great grandfather was a rabbi and in 1848 had moved from Prague to Budapest, where he married in the yellow-and-red-brick synagogue.

The Wallenberg book was “a transforming event in my life, personally and professionally,” Marton said, and she embarked on a career as a writer and author. Her fourth book, A Death in Jerusalem, an examination of the assassination of the first Middle East peacemaker, Count Folke Bernadotte, was issued by Pantheon Books/Random House in 1994. Her sixth book,The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World (Simon & Schuster, 2006) profiles four scientists, two filmmakers, two photographers and one author.

After she and Jennings divorced in 1994, Marton married Richard Holbrooke, who brokered a peace agreement among the warring factions in Bosnia that led to the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords. Holbrooke has assumed a major role in the Obama administration as special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan. Holbrooke, whose parents were born Jewish, was raised as a Quaker and has no religion in his background. Marton has taken her two children with Jennings, now young adults, on a “roots” tour of Budapest and she and her husband have visited the synagogue in Budapest and explored their Jewish identity.

In recent years, Marton has combined a career as an author with human rights advocacy. She is active in the International Rescue Committee, serves on the board of Human Rights Watch, was chair of the International Women’s Health Coalition and was a director and former chair of the Committee to Protect Journalists. She is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. In 2002 she received a Matrix Award for women who change the world.

“I try not to carry a lot of anger in my life,” she says. “I feel good and lucky in my parents, for the values they imparted to me. Their lives were more complicated than I realized. My parents never wanted to look back. They felt, as survivors of fascism and communism, that they had earned the right not to look back.”

NONFICTION

Standing By: The Making of an American Military Family in a Time of War

Standing By: The Making of an American Military Family in a Time of War

by Alison Buckholtz. (Tarcher/Penguin, 286 pp. $24.95)

Meet Alison Buckholtz of Washington, D.C.—a Jewish New-Yorker-reading, museum-going urbanite with a full-time job, desperate to make a new relationship with her military officer boyfriend work. Fifty pages later, in a cross-country shift of fate, we find Buckholtz in Anacortes, Washington, a tired, overworked mother of two. The precarious relationship in the book’s opening scene has clearly wended its way to matrimony, motherhood and small-town life—but Buckholtz’s husband is nowhere to be seen. He is on an aircraft carrier in Iraq, thousands of miles away.

Standing By documents the months of Buckholtz’s life when her husband, Scott, is away—seven months of de facto part-time single motherhood in a place far from home. In a chronological series of honest vignettes she describes the culture shock, exhaustion and emotional hardship of adjusting to a new lifestyle. Buckholtz peppers her account with little-known facts about the Navy and its traditions, devoting special attention to the iconic figure of the military wife. She paints vivid pictures of Anacortes and the Navy personalities who populate its streets. But more than anything else, the book is one of self-reflection, designed to examine her own journey from independent, urban woman to Navy mom and wife. Buckholtz doesn’t shy away from the fact that she never expected to take on such a role—to the contrary: Standing By is her attempt to make sense of, and to embrace, the unexpected turn her life has taken.

It is also the story of how a Jewish woman sought to find and tried to create the Jewish community she felt she needed in a place where it didn’t exist: Unlike during World War II, today Jews make up about one percent of active-duty military, Buckholtz writes. Being Jewish in the Navy, she and her husband discovered, is “different weird.” When, for lack of a nearby synagogue, she decides to open her home for Jewish service members for Rosh Hashana—buying halla and kosher wine and preparing brisket—no one shows up. On Yom Kippur, she had to say goodbye to her husband who was returning to duty. Opening the prayer book to the Yom Kippur service, she read the Unetaneah Tokef poem about how each person’s future is inscribed for the New Year, speaking to the anxiety she feels knowing that her husband will be flying jets on and off aircraft carriers in the months to come.

Buckholtz walks the reader through her family’s emotional travails. She earns the title of “Gone Mom,” as she calls it, struggling to keep it together for her children through the whirlwind of Scott’s absences.

More colorful are her descriptions of fellow Navy wives. As someone who “drank in feminism with mother’s milk,” Buckholtz is forced to put her assumptions to the test as she gets to know the women around her and, as an officer’s wife, learns her own role in the community. The women that Buckholtz finds herself admiring most, in many ways, are the polar opposites of the financially independent feminist prototype she has idealized since childhood. “I’ve thought a lot about feminism since I found myself, unexpectedly, assuming the most traditional role a woman can play,” Buckholtz muses. “And when I reflect on my experience I keep coming back to the idea that feminism is about choices that expand women’s lives rather than constricting them. Becoming a military spouse expanded my world, and the ultimate paradox is that I spent more time working within the domestic sphere than ever before.”

And her world isn’t the only one that expands—by recording her journey, Standing By expands ours as well. Buckholtz serves as an intermediary for the reader, guiding us through the intricacies of Navy family life as she is forced to learn them herself. Buckholtz laments the culture gap between the civilian population and the military and the American layman’s narrow understanding of the institution that defends his way of life. Her memoir—insightful and self-aware, if occasionally redundant—helps close that gap. —Ray Katz

Beyond America’s Grasp: A Century of Failed Diplomacy in the Middle Eastby Stephen P. Cohen. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 304 pp. $27)

Beyond America’s Grasp: A Century of Failed Diplomacy in the Middle Eastby Stephen P. Cohen. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 304 pp. $27)In the 1950s, when Israel was young and the Jerusalem Post a small paper that could afford only a part-time correspondent in the United States, I, as that correspondent, would travel to Washington once a month for a briefing at the State Department.

The head of the Israel desk, my briefer, was very proud of the Baghdad Pact, which had brought the Arabs into the cold war. Neither he nor his colleagues in the State Department could “seem to grasp that this was not the lens through which the Arabs saw the world,” writes Stephen P. Cohen, who is president of the Institute for Middle East Peace and Development in Washington. The cold war told them nothing about Arab nationalism and inter-Arab rivalry. In fact, says Cohen, American officials had difficulty distinguishing between communism and Arab nationalism.

Israel was not helpful; then as now the country relies on its army to solve its problems. Gaza was then a province of Egypt and fedayeen partisans had been raiding across the border. The Israeli Army held the Egyptian forces responsible for not controlling the fedayeen, just as last year Israel held Hamas responsible for not stopping Islamic Jihad rockets aimed at Sderot. So in February 1955, the Israel Army raided Gaza and decimated the Egyptian forces.

Although this minor raid had no resemblance to last year’s devastating attack, Cohen shows how it changed the history of the Middle East. President Gamal Abdul Nasser was shamed. Up to this point, he had reduced the army budget in favor of social acts in an attempt to alleviate Egyptian poverty. With the poor performance of his military in Gaza, he reversed his priorities.

Where did he get the arms to build up his forces? From the Soviet Union via Czechoslovakia. The Soviets gave him an attractive deal and Communist officials were firmly ensconced on Israel’s border.

This is a fact-drenched book. Briefly, it asserts that in every country the United States relates to it talks only to the elites, yet “The Street” influences the elites, and the street’s significance is heightened by the satellite television that pervades the Arab world. The end result in every country is hatred of America for its support of Israel. Cohen takes us on a sad journey through Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan.

We are learning, however. In Iraq and in Afghanistan, the American Army is making deals with subgroups. “They are the depositories of very strong feelings of particular identity,” Cohen writes in his finest professorial language. In plain words: The tribe comes first and in both countries we are working with the tribes and clans.

Civil society should do much more, Cohen contends. We should learn to listen and understand the other. We should overcome our distaste for mixing church and state and include religious bodies in the dialogue. Only via dialogue can reconciliation begin. —J. Zel Lurie

FICTION

Remedies

Remedies

by Kate Ledger. (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 373 pp. $24.95)

Though one of the two epigraphs to Kate Ledger’s impressive debut novel, Remedies, comes from a Kol Nidre meditation, it’s not clear until the last three pages how this tale of a marital and parental relationship in free fall resonates as a novel with a Jewish theme (the other epigraph is from Matthew Arnold’s poem “Dover Beach”). But when, at the end, the protagonist sitting in synagogue on Yom Kippur instinctively realizes that forgiveness precedes atonement, he acquires a humility and stature that Ledger has strategically withheld from him until that point.

Dr. Simon Bear, listed as one of Baltimore’s best physicians, and his elegant wife, Emily, a successful corporate public relations executive, see themselves as assimilated, nonobservant Jews; they are an attractive couple in an upscale suburban community, socially active, culturally aware and professionally engaged. Their beautiful home is on the historic register, and it’s where Simon has built an extension to house his medical practice. His hope, more like a mission, is to relieve his patients’ suffering. He believes he succeeds by spending inordinate amounts of time talking with them and by prescribing various medications to relieve their pain. He also wants to have Emily see how much he is appreciated. She is bored, distant, caught up in her own work, at least until she meets a former lover with whom she begins an affair.

Their problem, which they both tend to diminish in their different ways, is their sullen, rebellious 14-year-old daughter, Jamie, who, when the novel opens, has been asked to leave summer camp. Ledger has Jamie’s moody, hostile responses down pat, especially the monosyllabic, hate-filled exchanges she has with her mother. The Bears have another problem, however, that they are even more reluctant to acknowledge: the death, two decades earlier, of their 6-week-old son from fast-moving meningitis, which Simon (and other doctors) failed to detect.

For all his noble intentions, Simon is self-absorbed, arrogantly convinced of the efficacy of his benevolent medical ways and eager to talk about how much he cares. People, he says, are “desperate for his assistance…health and healing were essential.” Among those he would impress is a recent nursing graduate, whom he hires on instinct. A sharp-eyed, by-the-book young woman who reminds him of his daughter, Julie soon makes it clear that she opposes Simon’s reliance on prescribing narcotics. Though he would woo her to his way of thinking, especially after he has accidentally discovered in his stepfather’s drawer a Viagra-like drug that seems to have unusual pain-killing properties, he fails to see how his enthusiasms blindside him.

Even though a reader may sense what’s coming and feel a bit burdened by all the medical detail (Ledger worked for several years as a senior medical writer at Johns Hopkins), the author artfully develops a tale about countering pain into one about medical ethics, and, finally, the consolations of Jewish prayer. —Joan Baum

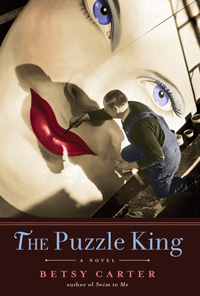

Betsy Carter is best known for her memoir, Nothing to Fall Back On, a book that mentions in passing how her mother’s German-born aunt Flora traveled back to Germany in l936 on a mission to rescue members of her family. The Puzzle King wraps layers of family legend (Carter’s term) and old-fashioned research around an imaginative core about how American Jews “made it” in America, how German Jews regarded themselves as true “Germans” in Germany and how both groups responded to the growing threats of Nazism. The result is a page-turner of a novel that follows Simon Phelps, the “puzzle king,” from 1892 to 1936, the years he spent in America.

Carter introduces the theme of puzzles early. Simon’s sketchbook is always with him as he chronicles what his environs look like. Even as a 6-year-old, on a ship bound for America, he entertains a homesick passenger with sunny pictures and then (talk about foreshadowing!) with a spur-of-the-moment jigsaw puzzle: He carefully tore the picture into odd random shapes and wrapped them up in another sheet of paper. “It’s a puzzle,” he told her. “Try to put it together.”

Later, Simon’s talents are discovered when, as a teenager, he produces an impressive sidewalk chalk drawing of heavyweight fighters. What follows, in a long, successful arc, is Simon’s career as an ad man, and then as the man who figured out how to make jigsaw puzzles from cardboard rather than, more expensively, wood. During the Depression, many families that could not afford more costly entertainments spent evenings putting together Simon Phelps’s intricate jigsaw puzzles.

Time magazine dubbed him “The Puzzle King,” and Carter makes sure we know that he is worth $1.7 million during a time when that was considered serious money. In the end, however, none of his worldly success matters—not as he wonders, decade after decade, about the family he left behind in Vilna. Perhaps some of his money might have gone into efforts to find these relatives, but it doesn’t. I am surely not the only reader who wondered why not.

On the other hand, his wife Flora’s family is alive and living in a small German town as history is poised to destroy them. Unlike Simon (who conveniently dies of a heart attack on the trip abroad), the flamboyant Flora takes action, presenting herself to the German consul and giving him an advance copy of Gone With the Wind. She also has fistfuls of money to pay for the documents necessary to ensure her family’s passage to America. The year is 1936. They make it to America where their offspring eventually includes Betsy Carter herself.

Because the novel interlaces chapters from an American Jewish perspective with the world seen through German Jewish eyes, it is clear, all too clear, that those who saw only what they wanted to see missed the dangerous anti-Semitism embedded on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Puzzle King is a fascinating read that might have been better had Carter allowed her characters to develop in less predictable ways and in richer swathes of language. Still, to add yet another compelling novel to the stack of immigrant Jewish novels already written is no easy feat. But to her credit, Carter has done exactly that. —Sanford Pinsker

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply