Wider World

Feature

Chiune Sugihara: Heroism in the Face of Evil

Dalia Tzura never expected to be reminded of the tragic fate of her family while traveling with an Israeli tour group through the bucolic heartland of Japan. Yet here she was in late November, emerging from a small Holocaust memorial museum in the town of Yaotsu with tears in her eyes. “I was deeply affected,” said the 74-year-old, whose father and mother both lost their entire families to the Nazis and rarely discussed the devastation with their daughter.

“I was living my life far from this, and now the pain and sorrow knock at my feelings,” said Tzura, who grew up in Israel, lived for a while in the United States and now resides in South Africa.

What stirred her feelings was the story that unfolds within the Chiune Sugihara Memorial Hall—a tale of heroism in the face of evil that features the Japanese diplomat who defied his government to issue visas for thousands of Jews, enabling them to flee Nazi persecution.

The Sugihara story has been told before but it is not nearly as well known as that of Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist whose tale of saving 1,000 Jewish workers was immortalized in the Steven Spielberg film, Schindler’s List.

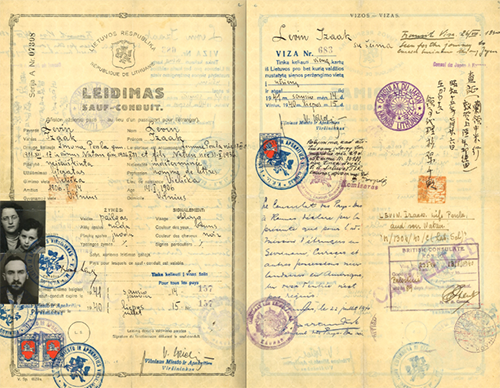

Sugihara’s actions were no less dramatic. With a pen and a stamp, he charted the course for Jews desperately seeking a path out of Europe when few escape routes were left.

Now, nearly 78 years after the rescue efforts and 34 years after Sugihara’s heroism first became public when Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and remembrance center, honored him as one of the Righteous Among the Nations, Japanese officials have launched a new campaign to bring attention to his courageous actions. (Read more about traveling to Sugihara’s Japan here.)

The story of Sugihara’s humanity is not only the story of the past, it is “very much alive today, especially in the increasing tensions of the world,” Hajime Furuta, the governor of Gifu Prefecture, Sugihara’s birthplace and home to the Sugihara memorial, told a group of visiting Jewish journalists in November. “These are the important lessons learned that we should disseminate and continue to express.”

In 1940, Sugihara, then 40, was stationed at the Japanese consulate in Kovno, Lithuania (today known as Kaunas), in part to monitor the maneuvering of the German and Soviet armies. In July of that year—nearly a year after Germany set off World War II with its invasion of Poland—he was first approached to issue transit visas to a small group of Polish Jews.

Among those to receive the first transit visas was the family of Nathan Lewin, a well-known attorney in Washington, D.C. “I don’t remember a minute of that long trip,” recounted Lewin, who was 4 years old at the time, but he knows Sugihara deserves credit for saving his family and others.

Lewin’s mother, a former Dutch citizen, used that lineage to convince the Dutch mission in Lithuania to issue bogus visas to Curaçao, declaring that an entrance visa to the Dutch Caribbean island was not required. Reaching Curaçao from war-torn Europe required crossing the Pacific Ocean, which is how Sugihara’s transit visas to Japan became the vital link.

Within days of signing those initial visas, Sugihara reportedly heard a clamor at the gates of the Japanese consulate. A group of 100 Jews, who had learned by word of mouth that he had issued the travel permits, pleaded with the diplomat to write even more to enable them to flee Nazi persecution. At that point, according to various accounts, he contacted the Japanese Foreign Ministry seeking permission to issue the additional visas, but the permission was never granted.

He was faced with an agonizing choice: Follow the orders of his state, which required certain conditions for visas, or save the lives of Jews, thereby risking his own personal and professional future.

He opted to save lives. His actions set off a chain of events that continued with a grueling and risky trip for the refugees that included traversing Russia’s vast terrain on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok. From there, with the help of the Japan Tourist Bureau that provided and manned the ships and helped distribute relief funds from American Jewish agencies, the refugees boarded the vessels that took them to the Japanese port city of Tsuruga. The Jews, among them many students and rabbis from the famed Mir Yeshiva of Lithuania, traveled from Tsuruga to Kobe and Yokohama, two cities where small, local Jewish communities—established with the opening of Japan to Western trade in the 19th century—took them in and cared for them while they awaited transit to America, Canada, Australia and other countries.

Even after Japan closed the consulate later that summer, at the orders of the Soviet authorities who had by then annexed Lithuania, Sugihara reportedly continued writing the visas from his hotel room, and later from the train as he was departing the city. All told, he is credited with writing more than 2,000 visas in a period of one month. With children and other family members able to travel on the visas, he saved an estimated 6,000 individuals from the Nazis.

Today Japan is investing considerable resources to publicize the Sugihara story. The Japanese government had hoped to get a boost in visibility for the “Visas for Life” program under the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. Officials expressed deep disappointment when they found out in October 2017 that the United Nations body had rejected the application. No reason was given and the Japanese government is considering reapplying in the future.

Despite the setback, the Gifu Prefecture, partnering with JTB, the Japan travel agency, and the national government, is moving forward with a 20-million yen (nearly $200,000) campaign to encourage primarily Israeli and American Jewish visitors to the region. Six local municipalities have also banded together to develop the Sugihara Survivors Remembrance Route, which includes visits to the Sugihara memorial in Yaotsu, where Sugihara is believed to have been born, and the small Port of Humanity Museum in the coastal town of Tsuruga, where the refugees landed.

The emphasis on the diplomat’s good deeds reflects a dramatic reversal from the way official Japan first treated his actions. After the consulate in Lithuania closed, he was sent to Berlin, then Prague and finally Bucharest, where, at the end of the war, he was imprisoned in a Soviet internment camp.

When he returned to Japan in 1947, he was forced to resign from the Foreign Ministry.

There are conflicting accounts about whether he lost his job as a direct result of his actions. Some officials point to the fact that many diplomats lost their positions after the war, when Japan was under Allied occupation and its diplomatic corps was severely curtailed. Even the Sugihara memorial museum presents a nuanced account of his fate, falling back on the words of his wife: In 1947, two months after he and his family arrived back in Japan, both he and his wife were called to the Foreign Ministry, where he was laid off, according to an explanatory panel at the museum. “According to Yukiko Sugihara, Sugihara told her he was dismissed because he had taken it upon himself to issue those visas. After his retirement, Sugihara faced many financial hardships.” He had different jobs toward the end of his life, including working at a trading company in Moscow.

One thing is certain: Japan didn’t officially recognize him for his heroic actions until 2000, 14 years after his death at the age of 86, when a plaque to Sugihara was erected at Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo. That it took so long was not a big surprise to Lewin, the Washington attorney, who spoke two months later at a ceremony in Osaka honoring Sugihara on the 100th anniversary of his birth.

“Were they going to make a hero of someone who violated his instructions?” asked Lewin, 82. “Not until the rest of the world recognized his actions did Japan say it was time.”

Some might wonder whether Japanese officials have now moved from honoring his legacy to using it to bolster tourism among Israelis and American Jews, and perhaps even more importantly, to soften an otherwise brutal record of Japan’s actions during World War II. Both motivations seem plausible, but there also appears to be a genuine interest in spreading Sugihara’s values, including among Japanese citizens and schoolchildren.

Given the limited number of potential Israeli and American Jewish tourists, officials acknowledge they will unlikely get a return on their investment. “If we are able to see a profit in this over the next 10 to 20 years, that’s fine, but that’s not the main goal of the project,” said JTB’s regional president, Hiroshi Matsumoto. “Our main goal is to further deepen the connection between the Japanese and Jewish people.”

With that quest, they no doubt will continue to count on the good will of people like Tzura, who encountered Sugihara’s story for the first time while traveling in Japan, and Lewin, who grew up with the diplomat’s actions deeply embedded in his family history and sees Sugihara’s legacy quite clearly.

“Rescue and saving lives should be an unconditional human obligation,” he said, noting that Sugihara was one of the rare souls during the Holocaust who took that obligation to heart.

Lisa Hostein, executive editor of Hadassah Magazine, traveled to Japan as the guest of the Gifu Prefecture, which sponsored these stories but was not involved in their production.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply