Israeli Scene

Life + Style

Notes from the World: The Annual Song of Songs

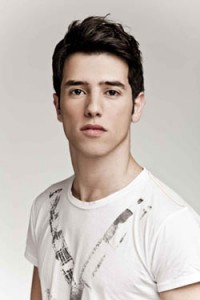

This month, Israeli heartthrob Harel Skaat will get to fulfill a longtime dream when he represents his country in the 55th-annual Eurovision music contest, a yearly European musical extravaganza.

A second-place winner of the second season of A Star Is Born, Israel’s version of American Idol, the handsome 28-year-old will be singing the ballad “Milim” (words) in his attempt to bring a victory back to Israel for the first time in 11 years: The time-honored pop music competition will take place in Oslo on May 27. Some European betting Web sites have placed Skaat in second place behind Safura, representing Azerbaijan, while others have him winning.

This is not the first time the Israel Broadcast Authority selected an artist fromA Star Is Born to represent Israel at Eurovision. In 2005, Shiri Maimon, first runner-up in the 2003 season, placed fourth in Eurovision and, in 2008, Boaz Mauda, the 2007 series’ winner, came in ninth.

Practically unknown in the United States, Eurovision (www.eurovision.tv) is one of the longest-running television programs broadcast throughout Europe, Asia and parts of the Middle East. Best known for flashy costumes, sugary pop lyrics and highly choreographed dance performances, it has launched the careers of numerous singing stars. Swedish pop sensation ABBA went forth to conquer the world following their 1974 winning Eurovision performance of “Waterloo,” and Cliff Richard, Julio Iglesias and Celine Dion have strutted their stuff on the Eurovision stage.

In its early years, entries had to be sung in one of the country’s national languages, but the requirement changed over time. English has become the language of choice, though some entries, such as Achinoam Nini and Miri Awad’s “There Must Be Another Way” from last year, combine two native languages with English—and others are even sung in a fictional language. Skaat will perform “Milim” in Hebrew.

Though not geographically part of Europe, Israel has participated in the competition since 1975. Grateful at the time for the European Broadcast Authority’s invitation, joining Eurovision symbolized one more step toward the recognition Israel so coveted.

“[Israelis] liked that feeling of leaving the periphery,” says Motti Regev, a professor of sociology at the Open University in Ranaana. “The value came from being a part of…an international cultural exchange. It’s very European.

“The respect is in the participation,” Regev continues. “If [the entry] was good that was good, but [the quality of the song] was less important than the actual participation in the competition.”

Ireland holds the winning record, nabbing the top spot seven times—three in a row starting in 1992—while Portugal has participated the longest, 43 competitions, without a win.

The Jewish state has done relatively well, winning three times: in 1978 with “A-Ba-Ni-Bi,” sung by Izhar Cohen and Alphabeta; “Hallelujah” performed by Gali Atari and Milk and Honey the following year, which became a sort of Israeli anthem; and, in 1998, Israel garnered its third win with flamboyant transsexual performer Dana International and her rendition of “Diva.”

Though traditionally the winning country hosts the following year’s competition, Israel was unable to host in 1980 because of the financial strain of producing two events back-to-back. Israel then elected not to compete that year because the scheduling coincided with its Memorial Day, Yom Hazikaron.

Yael Robin, 50, Jerusalem art teacher, artist and Eurovision fan, recalls how, as an art student living in Belgium in 1998, she was filled with national pride whenever she strode into a store, restaurant or café and was greeted by the pulsating beat of Dana International’s winning song.

“The song was everywhere I went,” says Robin. “I felt proud to be an Israeli; especially that we won the contest with a song by a transsexual.”

But, in recent years, Israel has had its less-than-shining moments, such as in 2006 and 2007, when it scored among the lowest in the contest.

Eddie Butler, a member of the Black Hebrew Israelite community of Dimona, represented Israel in 2006 with the ballad “Together We Are One” and finished in 23rd place out of 24. Seven years earlier, Butler had represented Israel as part of the band Eden together with his older brother, Gabriel, and Rafael Dahan and Doron Oren. Their song, “Happy Birthday”–which, like Butler’s losing song, was performed in both Hebrew and English–finished in a respectable fifth place.

In 2007, it was Israel’s quirky pop band Teapacks’ turn to disappoint with a poor showing of 24 out of 28 with the Hebrew, English and French lyrics in “Push the Button,” failing even to reach the finals.

Israel finished 16th in last year’s Eurovision, held in Moscow. Nini and Awad became the first Jewish-Arab duo to represent Israel in the contest. Coming at the end of Operation Cast Lead, the choice of Nini and Awad and their song was labeled propaganda by detractors.

In its early years, Eurovision was an institution in Israel. With only one television channel to watch, most Israelis share in the collective memory of national excitement over which song would represent their country, then later the exhilaration of galvanizing support for its singer. People were glued to the television late into the night to hear the final results, arriving to school and work bleary-eyed the next day.

Today, Israel no longer craves international recognition as it once did. But still, every year as Eurovision rolls around, the competition elicits national attention—especially for the pre-contest song selection broadcast on national television to choose the official entry.

“The competition is attractive simply because of what it offers: an international singing contest, like A Star Is Born but on a larger scale,” says the IBA’s Assaf Azoulay. “The competition has 100 million viewers…. For a lot of people it is just spectacular.”

Indeed, says Regev, the European gay community–and the Israeli gay community in its wake–has especially embraced the competition. “[Eurovision] is very ‘camp’ with a lot of show and theatrical fashion,” adds Regev.

In the past, a pre-Eurovision competition was held to select that year’s performer but, more recently, the artist has been pre-chosen by an IBA committee. Now, via televoting, television viewers participate only in the song selection.

Dissatisfied by the IBA’s role as sole arbitrator of who will represent Israel, Knesset Member Alex Miller of the Yisrael Beiteinu Party called for a parliamentary meeting in January to clarify how the IBA chooses the contestant.

“All these preparations are paid for by the Israeli taxpayers, and I wanted to know who decides who goes and how it is organized,” says Moscow-born Miller, who moved to Israel in 1992 at age 15. “After all, we have not been able to bring the Eurovision to Jerusalem since 1998. We have to have a winning strategy to prepare for the contest so we know we have done the best we can.”

Several Arab countries that fall within the European Broadcasting area and who are, like Israel, eligible to participate in Eurovision–Tunisia, Morocco and Lebanon, for example–abstain because of Israel’s inclusion.

Morocco, however, participated in Eurovision in 1980, the year Israel sat out. In 2005, Lebanon incurred a fine when it withdrew from competition at the last minute; Lebanese television would have violated contest rules had it not broadcast Israeli segments.

Though it is unrealistic to expect Eurovision to affect politics, says Azoulay, it is important that Israel participate to showcase its nonpolitical side–especially to a Europe that tends only to see the militaristic aspect of the country.

“We export culture,” he says. “Israel has much to offer to the art world and it is important the world sees it and knows how to judge it fairly.”

Though there have long been accusations of anti-Israeli voting, Azoulay prefers to believe the songs are judged solely on their artistic merit. Nevertheless, judging from talkback comments on various Internet sites, not everyone sees it that way. One writer argued that Dana International should be “arrested for killing Palestinians.” And several years ago, an Internet petition asked Eurovision to drop Israeli participation. But there are bright spots of support. A viewer from Iran wrote on one site in favor of Shiri Maimon, and fans from all over Europe wrote in congratulating Israel on the selection of Skaat, commenting on his good looks and wishing him luck.

Talk of political bias flourishes among Eurovision fans. Some observers have noted the strong support Greece and Cyprus have given each other since popular voting was introduced in 1998, though they point out this may be due to similar tastes in music rather than politics. The televote has also created apparent voting blocs in the Balkan states as well as given Turkey a high number of votes in West European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, home to large Turkish émigré communities.

Academics have even weighed in on changing voting patterns. One researcher in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation used the straightforward terms “Western,” “Mediterranean” and “Northern” blocs to identify clusters between 1975-1992. Another termed different blocs in the overlapping years of 1975-2002 as a “Viking Empire” bloc, which included the Scandinavian and Baltic countries and Ireland; the “Warsaw Pact” bloc, consisting of Russia, Romania and former Yugoslavia; and the “Maltese Cross” bloc centered loosely around Malta.

According to Radio Free Europe, it was the prevalence of these voting blocs that spurred longtime BBC Eurovision correspondent Terry Wogan to step down last year, quoting the 35-year veteran as saying, “Those who care will have had it up to here with the blatant political voting.”

In an attempt to help reduce the power of voting blocs, last year Eurovision reintroduced national juries that control 50 percent of a country’s vote alongside the televotes for the winner.

Historically, Israel has received the most votes from France, Switzerland, Finland, Portugal and Germany.

In 2002, at the height of the intifada, Israeli media reported that the Israeli delegation headed by Sarit Hadad had encountered anti-Israel comments throughout their stay in the Estonian capital of Tallinn. That same year, Eurovision television announcers in Sweden and Belgium made blatant anti-Israel comments urging the local audience not to vote for Israel.

Following geopolitical changes in Europe, the contest has grown with more countries from Eastern and Southern Europe taking part, pushing up the number of participating countries to 43.

“The Eurovision is very popular in Central Europe, more popular than in other countries,” says Azoulay. “They are living what Europe and we experienced in the past.”

This year’s controversy appears to be between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey. Internet sites were rife with vitriolic attacks between Azerbaijan and Armenian fans. Last year, the BBC reported that several people in Azerbaijan who voted for the Armenian song were questioned by the Azerbaijan police for being “unpatriotic and a potential security threat.” The two countries have been at odds over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Turkey protested Armenia’s inclusion this year, accusing the nation of touching upon the Turkish genocide of the Armenians–that it refuses to acknowledge–in lyrics sung by Eva Rigas, representing Armenia. Meanwhile, back in Armenia, fans of one of the losing contestants charged that the phone-in voting system had been rigged in favor of Rigas.

In Israel, Robin still enjoys gathering with friends to share a glass of wine and some laughs on the evening of Eurovision as they take in the increasingly garish and revealing costumes and giggle at the gyrating hips, flashy lighting and special effects.

“Every year [the performances] get more extreme,” says Robin, recalling how in her college days watching Eurovision even took on some cult aspects. “We would meet at somebody’s home to watch it together and drink some wine and beer. We would scream when we had to scream and laugh at the dancing and the performances. Nobody takes the whole event too seriously but they take the winning seriously. And it is fun to watch.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply