Books

Feature

Reading Myself in Another: A Look at the Life of a Prestate Tel Aviv Journalist

It’s rare, but it happens. You meet someone new and are stunned to discover that you have somehow lived parallel lives—your experiences and world outlooks uncannily mirror each other’s. There is instant affinity and you become hungry to learn all you can about her.

That was my feeling when I encountered Dorothy Kahn Bar-Adon. We both spent our childhoods as Reform Jews living a comfortable, thoroughly assimilated life in the United States, she in Philadelphia, Pa., and then in Atlantic City, N.J.; I in Barrington, R.I. We were both writers from a young age, drawn to journalism with strong career aspirations. Our Jewish identity, passion for storytelling and desire to be part of something new and adventurous led us on the same journey. Both Bar-Adon and I left all that was safe and familiar for the challenges of life in the bustling, growing, diverse city of Tel Aviv.

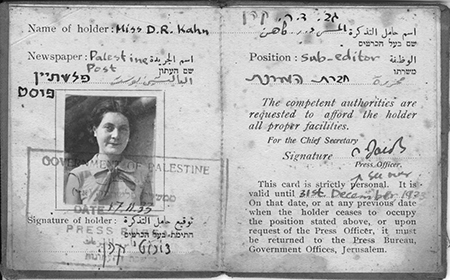

We were among the masses of Jews coming from around the world to the Middle East seeking refuge or meaning. We were trying to redefine our lives and identities while building a country still wrestling with its own self-definition. Bar-Adon and I even got jobs at the same English-language newspaper—The Jerusalem Post—and began reporting on the ever-changing scenes of Palestine/Israel from almost the moment we arrived, and never stopped.

The major difference between us is this: Bar-Adon, who was born in 1907, traveled to Tel Aviv by boat in 1933. I made my trip on an El Al jet from Washington, D.C., in 1993, decades after her death in 1950.

Despite this, I feel that I know Bar-Adon intimately, thanks to the treasure trove of writing she left behind. In her short life, she impressively produced five books, hundreds of articles for The Palestine Post—the forerunner of The Jerusalem Post—and other publications, and left letters written to friends and family back in the United States as well as selections from her personal diaries. I discovered her in the recently published Writing Palestine 1933-1950: Dorothy Kahn Bar-Adon (Academic Studies Press; edited by Esther Carmel-Hakim and Nancy Rosenfeld).

Three years after arriving, Bar-Adon penned an imaginary dialogue in response to the question, “What is it like being a reporter in 1936 Palestine?” She answers almost precisely the way I would about my experiences in Israel:

[The country is] as small and convenient as a pocket comb. If you hear about a story on the farthest frontier, you can be on the scene within a few hours. You can get anywhere in the country and home again between breakfast and dinner—with your story safely up your sleeve or under your hat. Surely, this is a paradise for journalists who have a reputation for wanting to be everywhere.

Bar-Adon somehow manages to be everywhere. She captures a remarkable slice of history in the years leading up to the establishment of the state, describing life in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and the small northern village of Merhavia. She relates how the influx of German Jewish immigrants, driven to Palestine by the rise of Hitler, transformed the country through medicine, culture and architecture. She notes how Jews wrestled to reconcile their Zionist ideals with the sobering realization that the Arabs—whom she refers to as “our cousins”—were increasingly unhappy with the growing Jewish presence and began to rise up against it. In 1936, she writes:

The Arab is my close neighbor. He is my fellow citizen. He is the man with whom a few months ago I broke bread. He is the man who today is spilling the blood and burning the crops of my people. He is the man with whom a few months from now I hope I shall be breaking bread again.

The sights, sounds and smells she conveys in her scenes of life in Tel Aviv are still utterly recognizable today in the heady mix of cultures in the East-West encounters on the streets, in the overflowing bars and cafés and on the Mediterranean coast. Her description of a lively Simchat Torah celebration in the streets of Tel Aviv in 1935 is vivid:

Large circles of hora dancers stretched down Allenby Road to the sea. Blue-bloused youths swayed to the tune of their own singing—then others joined the circle—middle-aged women—old men—tourists. The circles broke up. New ones formed. Nearby a vast crowd was gathered around a young couple who were executing a lively hora. Hasidic melodies intermingled with pioneer songs. Joy of the evening seemed to infuse the dancers with a strength beyond themselves. No one was drunk but everyone was intoxicated.

Also ringing true is Bar-Adon’s description of how newcomers react to the everyday use of the Hebrew language:

It is amazing…that this Biblical tongue should be the key to everyday business life. By the time you make a few purchases and order a few meals in Tel Aviv, you are able to disassociate Hebrew from shepherds, kings and prophets and begin to think of it in terms of toothpaste and fried eggs.

The scene she draws of the Tel Aviv beach is also familiar:

The girl in the exaggerated suntan bathing suit who would be at home on the beaches of Miami or Lido is rubbing shoulders with two Muslim women who have daringly lifted their veils for a moment to glimpse the sea. A substantial looking real estate dealer from Brooklyn applies olive oil to a newly acquired sunburn while an Arab in the neighboring chair gathers his purple silk robe about his feet and settles down to enjoy “the big parade” for a few hours.

Sixty years later, that parade continues, enhanced by French Jews and Asian tourists and youngsters on Birthright Israel trips. Today, we worry about Iran and Hezbollah and ISIS—back then, there was the ominous backdrop of the rise of Hitler.

In a moving 1938 article in The Palestine Post, Bar-Adon describes German Jews wistfully touring the country, knowing it will be their last visit but unable to imagine the tragic fate that awaits them when they return home. “For them, Palestine is unattainable, the ‘Paradise Lost,’” she observes. “They are past middle age and they cannot take money out of Germany: to start life again in a strange country, virtually penniless, is terrifying.”

Reading that passage, I want to jump into the text and tell them not to go back, to stay in Palestine; even if they have to start over, at least their lives will be saved. Similarly, when Bar-Adon reports on the Jewish refugees interned in detention camps in Cyprus after World War II, waiting for British authorities to allow them in, I want to reassure the scared children behind barbed wire that it will all be O.K., that decades from now they will be proud, secure Israelis with children and grandchildren, with satisfied lives and careers to look back on.

It makes me wonder: Sixty years from now, what will someone reading my stories wish they could shout at me? What is it that I am not seeing? What missteps are we making at this turbulent time in history?

Of course, there is no way to know. All that my future readers will be able to do, as I did when reading Bar-Adon’s work, is appreciate how, despite the passing of the years, the emotional core of our unique country remains the same.

This woman whom I have never met feels not just like a colleague, but like a sister.

Allison Kaplan Sommer lives in Israel and writes on culture and politics, primarily for Ha’aretz.

The Hadassah Connection

Dorothy Kahn Bar-Adon’s brief life intersected with Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold and Hadassah Hospital, and a new collection of her essays and articles, Writing Palestine 1933-1950, offers several glimpses into those ties.

A close observer, Bar-Adon contributed both as a journalist to the English-language Palestine Post and other papers and as a publicist for many Jewish organizations, at one point becoming publicity director of Hadassah Hospital. She also worked for Youth Aliyah, which Szold was then leading, working to save young Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe. Bar-Adon described how Szold, “at the age of 73 assumed the gigantic task of settling these children and whom I recently heard referred to by a pioneer from Ein Harod as ‘the belle of the Emek….’ ”

Before Bar-Adon moved to Palestine at the age of 26 in 1933, she had asked Reform Rabbi Stephen S. Wise for letters of introduction to people who could help ease her adjustment. In response, he gave her letters to Szold, who had made aliyah in 1918, and to Irma Lindheim, the second president of Hadassah, who made aliyah in 1933.

Bar-Adon said of Szold that she was among those American and British Jews who in those years had “proved their ability and devotion and success” and “who is a shining example in more than one sphere.”

Bar-Adon’s ties with Szold went even deeper: Szold became godmother to Bar-Adon’s only child, son Doron, who was born in 1940.

Sadly, Bar-Adon’s final connection to Hadassah was tragic. In July 1950, she was taken to Hadassah Hospital, where she was diagnosed with untreatable kidney disease. She died there at the age of 43. —Zelda Shluker

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply