Books

Fiction

Books: Puzzling Out Pages That Challenge Imagination

Beatrice and Virgil: A Novel

Beatrice and Virgil: A Novel

by Yann Martel. (Spiegel & Grau, 224 pp. $24)

To get something out of Beatrice and Virgil, a reader must engage in several acts of faith: faith that the abstruse details will prove meaningful, that the knack for indelible storytelling that won Yann Martel the Man Booker Prize for Fiction for Life of Pi (Marwer) will rematerialize and that it will all produce a luminary way to examine the Holocaust. And get something the faithful reader does.

The novel’s protagonist, Henry, is a successful author with a big next idea: a “flip book” about the Holocaust that will comprise an essay behind one front cover and, when flipped vertically, a work of fiction behind the other. This format, he foresees, will remind readers of the way the Holocaust itself turned the world upside down and cannot be closed neatly behind a back cover. Its very resistance to categorization will help to chip away at the carapace of tradition that, he laments, limits the Holocaust discourse.

But industry experts spurn the manuscript, and their rejection drives Henry to take up residence—as well as Spanish, amateur theater and the clarinet—in a conspicuously unspecified city, and also to give up writing. So he believes, anyway.

Until this point, the book mostly ignores the reader’s need to be pulled forward, offering no conventional suspense; instead, the plot progression feels like a person walking forward while looking at an engaging conversant directly behind. This is due, in part, to Henry’s character, for he is a man lost in thought, and thus the motivation to go on turning pages must come from beyond the book, from within the reader, who must be thoughtful.

This changes when, in Henry’s regular flow of fan mail, there appears a parcel peculiar enough to shake him from his routine and out in search of its sender. And with the man he finds—a gaunt taxidermist with no social graces to speak of—Henry forges a dubious relationship and begins collaboration on a script for the most unorthodox of plays, one that, he suspects, pursues the very same ideal that cost him his career.

Because of certain details, it’s easy to speculate that Martel wrote Henry and his tribulations autobiographically. Like Martel, Henry has two published novels, the second of which features exotic animals and fared marvelously. Neither author is Jewish, but both profess commitment to fostering long-term dialogue about the Holocaust. Ensconced in this, many of the book’s expansive bits—quirky and profound and told via an omniscient narrator who doubles as Henry’s interior monologue—read like the tenets of what one can imagine was Martel’s own rejected essay. Thus it has an aspect like that of a babushka doll, or a creature eating its own tail, or perhaps an M.C. Escher lithograph: The book as a whole is Martel’s answer to questions posed within the book.

Beatrice and Virgil is at once blatant and subtle, and its own unorthodox aspects make it a bit of a stunt, one that might not have found an audience from an author less established than Martel. In this regard, it’s fortunate that it was he who endeavored to take such a chance: Together, his stature and facility have brought to light something quietly phenomenal and enormously important. —Rachel Lieff Axelbank

Rachel Lieff Axelbank is a freelance writer and M.F.A. candidate in the nonfiction writing program at Sarah Lawrence College.

The Glass Room

The Glass Room

by Simon Mawer. (Other Press,

405 pp. $14.95, paper)

British author Simon Mawer has pulled off a literary tour-de-force in The Glass Room, a novel that blends love, art, loneliness, terror, betrayal, sex, tragedy and architectural brilliance in one original and compelling work.

The story uses the see-through design of a glass house as an enduring metaphor, first as a family home, then a heinous Nazi laboratory to craft a “master race” and, finally, a world heritage site, to reflect 66 years of turbulent world history.

Viktor and Liesel Landauer, wealthy newlyweds, commission a visionary architect to design a home that can also serve as a showplace for their sophisticated friends and business colleagues. Here they can host musicales, soirees and other gatherings and perhaps score points as they climb the social ladder.

The avant-garde design is marked by a large room with floor-to-ceiling glass walls, called the Glass Room, and is partitioned by a wall made of onyx that changes appearance with the sun’s position. “It had become a palace of light,” Mawer writes, describing the dazzling house, “light bouncing off the chrome pillars, light refulgent on the walls, light glistening on the dew in the garden, light reverberating from the glass.”

Just as structural restraints are lifted in the building of the revolutionary house so, too, are the cultural and business restrictions of the era. (The fictional house was inspired by the real Villa Tugendhat, an icon of Modernist architecture designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and built between 1928-1930 in today’s Brno, Czech Republic.)

The Glass Room asks readers to imagine the construction of the house against the destruction of cultural Europe. Viktor is an idealist who rejects the trappings of religion, aristocracy and nationalism. Naively, he sees a future state “in which being Czech or German or Jew would not matter, in which democracy would prevail and art and science would combine to bring happiness to all people.”

Viktor is Jewish and Liesel is not, but they harness their dreams to their house. Liesel puts family first, but proves all too human as she succumbs to the advances of her best friend, the plucky Hana. Viktor also accedes to human weakness, befriending a Jewish prostitute in Vienna and taking her as a mistress.

Although the house is a symbol of a new beginning for fledgling Czechoslovakia, the end of the dream comes quickly as the Germans advance and invade. As the world spins into war and chaos, the house is the only constant.

The Landauers escape to Switzerland and then make their way to the United States. The house survives the Nazis, the Communists and the Czechs’ Velvet Revolution. Oh, what tales this house can tell! Viktor’s mistress turns up at the house as a refugee and Liesel innocently hires her as a nanny. Liesel’s friend, Hana, provides unexpected spark, wit and intelligence. She manages to survive the war with sex and cunning, and later leads the campaign to preserve the Modernist masterpiece.

The plot spins on a number of unlikely coincidences, tying up The Glass Room in a neat, enduring little package of redemption. The passions evoked by the story are mesmerizing and unforgettable. —Stewart Kampel

Yom Kippur in Amsterdam

Yom Kippur in Amsterdam

by Maxim D. Shrayer. (Syracuse University Press, 152 pp. $24.95, paper)

Maxim D. Shrayer first wrote short stories in his native Russian and, later, in English after immigrating to America. Yom Kippur in Amsterdam is his first collection of short stories, tales of love, friendship, estrangement and the search for self as a stranger in a strange land.

In eight stories, Shrayer presents smart, sophisticated, modern-day Russian Jewish immigrant characters who confront age-old questions of belonging, loss for a life left behind and religious identity. He captures these experiences with imagination, clarity, tenderness, humor and touches of mysticism that echo the writing of Isaac Bashevis Singer.

In the opening story, “The Disappearance of Zalman,” set in Connecticut, Mark Kagan, a sometimes-brooding Jewish graduate student, ponders whether to break off his long-term, long-distance relationship with Sarah, a Catholic woman he met at a poetry reading. “The Jew in him—the Russian Jew—rejected that which the lover in him still ached for.” A conversation with the university rabbi leaves Kagan flat and unmoved. Yet, when Kagan connects with Zalman, a yeshiva student, he begins weekly Hebrew lessons with him.

Readers are offered a glimpse into Kagan’s inner struggle: “He didn’t think of himself as ‘Russian,’ although he still spoke some Russian with his parents and poured white vinegar over the meat dumplings he bought frozen at the Russian store when he visited his parents in Boston—and cooked for himself at home.”

The title story also explores the vexing question of intermarriage. Jake Glaz, a successful young Russian émigré, is distraught because his Catholic girlfriend will not convert. Alone, on his way home from a vacation on the Riviera, he stops in Amsterdam during Yom Kippur, “a beautiful place for a Jew to atone.” There is a palpable love of the city in richly detailed descriptions of Glaz’s misty walks along the canals, meals of herring that remind him of his Soviet childhood, and Glaz’s observance of Yom Kippur in the centuries-old Portuguese synagogue in the old Jewish quarter. Faith and hope trump despair.

Slowly, organically, other realities emerge in Shrayer’s stories, shedding light on the hidden hardships that come with the immigrant experience. —Penny Schwartz

Nonfiction

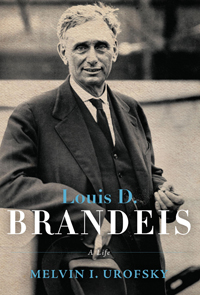

Louis D. Brandeis: A Life

Louis D. Brandeis: A Life

by Melvin I. Urofsky. (Pantheon Books, 953 pp. $40)

In the 1930s, as United States Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis approached his eighth decade, a number of government officials, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, began referring to the progressive reformer, jurist and Zionist leader as “Isaiah.”

Sure, at times he was far from prophetic; much of Brandeis’s political and social philosophy is more in line with 19th-century agrarian America than 21st-century sensibilities. But Melvin I. Urofsky’s exhaustively researched, admiring biography—a doorstopper, to be sure—describes a multifaceted life that often appears presciently relevant to our own perplexing times.

Perhaps there is no better example than Brandeis’s firm conviction that the operations of commercial and investment banks need to be separated—he feared both the concentration of wealth and power and what he often referred to as “the curse of bigness,” a phrase eerily similar to “too big to fail.” (Many today have cited the unraveling of the 1933 Glass-Stengal Act under the Clinton and Bush administrations as a major cause of 2008’s economic meltdown.)

In describing the Kentucky-born Brandeis’s early law career and forays into countless issues of local and national significance at the dawn of the last century, the author makes a compelling case that, even if Brandeis had never been appointed to the high court, his life would have made a compelling biography. In 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson tapped his trusted informal adviser for the Supreme Court, Brandeis was one of the most influential Jews in the country, in many respects a towering figure.

So how did the enormously successful, highly assimilated individual lacking even basic Jewish literacy become the leader of American Zionism, helping to bestow upon it legitimacy and prestige? Why did he undergo a “conversion” similar to Theodor Herzl’s?

Historians have debated this point for decades, and the author puts forth several theories while at the same time acknowledging how elusive the truth might be since Brandeis rarely revealed his inner self in correspondence. In Urofsky’s view, the activist’s embrace of Zionism stemmed from his reading of American democratic ideals. In a different context, this argument is still being debated today: How much do America and Israel’s interests overlap? In the end, Brandeis’s reasons for throwing his heart and soul into the establishment of a Jewish homeland may always remain somewhat of a mystery.

Don’t expect the storytelling techniques of a David McCullough, whose biographies read like novels. Yet, Urofsky does round out the picture of Brandeis’s personal and family life, his love of his grandchildren and devotion to his wife. It might not be a page-turner, but this book deserves a place on the shelf of anyone interested in the history of the Supreme Court, American Jewry or, indeed, the development of the nation as a whole. —Bryan Schwartzman

Bryan Schwartzman is a staff writer for the Jewish Exponent in Philadelphia.

Remember

Pictures That Tell the Story

Rediscovering Traces of Memory: The Jewish Heritage of Polish Galicia Photos by Chris Schwarz. Text by Jonathan Webber. (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization and Indiana University Press, 186 pp. $27.95)

For 15 years, Schwarz and Webber worked to document southern Polish Jewry, who lived in the 19th-century Austro-Hungarian Galicia province. The 73 photos in this book are part of a much larger trove found in the Galicia Jewish Museum (www.galiciajewishmuseum.org), which Schwarz opened before he died in 2007.

The thematically arranged images and text are richly detailed. First, there are the ruins of Polish Jewish life: traces of cemeteries and interiors and exteriors of destroyed synagogues. The grandeur of past Jewish life is visible in still magnificent synagogues and ornate headstones. Sites of massacre and destruction during the Holocaust include a mass grave for 7,000 in a forest and a remnant of the Warsaw Ghetto wall. If Poland was once the epicenter of world Jewry, Belzec, where 450,000 Jews were gassed, is its largest graveyard. How is the destruction being remembered? At Belzec, a narrow path follows the victims’ route to the gas chamber. At its end is a granite wall inscribed with a quote from Job: “Earth do not cover my blood: Let there be no resting place for my outcry!” Elsewhere there are restored cemeteries and synagogues.

Finally, who is remembering the destroyed people? There are images of youngsters on March of the Living, visiting survivors, Polish officials—though there are few public memorials—and non-Jewish Poles who are keeping Jewish culture alive in festivals and music.

A memorial wall in Krakow relays both the Jewish presence and the destruction: It is made up of fragments of smashed tombstones.—Zelda Shluker

Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers

NONFICTION

1. Have a Little Faith: A True Story by Mitch Albom. (Hyperion, $23.99)

2. When I Stop Talking, You’ll Know I’m Dead: Useful Stories from a Persuasive Man by Jerry Weintraub with Rich Cohen. (Twelve, $25.99)

3. The Bedwetter: Stories of Courage, Redemption, and Pee by Sarah Silverman. (Harper, $25.99)

4. Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue and Unthinkable Choices by Mosab Hassan Yousef with Ron Brackin. (SaltRiver/Tyndale, $26.99)

5. The Council of Dads: My Daughters, My Illness, and the Men Who Could Be Me by Bruce Feiler. (William Morrow, $22.99)

FICTION

1. Sarah’s Key by Tatiana de Rosnay. (St. Martin’s Griffin, $13.95, paper)

2. Beatrice and Virgil: A Novel by Yann Martel. (Spiegel & Grau, $24)

3. City of Thieves: A Novel by David Beniof. (Plume, $15, paper)

4. The Three Weissmans of Westport: A Novel by Cathleen Schine. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $25)

5. People of the Book: A Novel by Geraldine Brooks. (Penguin, $15, paper)

Courtesy of www.MyJewishBooks.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply