Books

Fiction

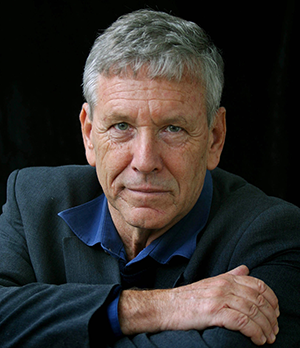

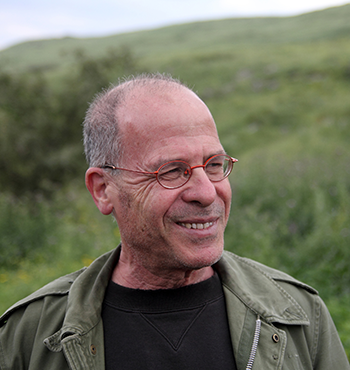

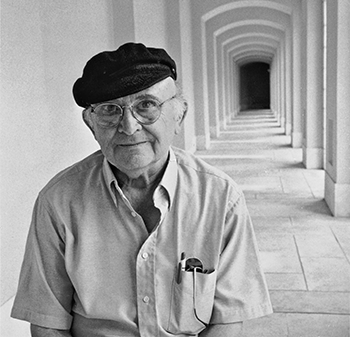

Amos Oz, David Grossman, Meir Shalev and Aharon Appelfeld

The English translations of four Israeli novels landed almost simultaneously in late 2016 and early 2017. Taken together, they provide fascinating insight into the cultural shifts of Israeli society 50 years after the Six-Day War. Israeli novelists have shifted emphasis from the male-dominated army to a greater focus on women. Even though the effects of needing and having a standing army in Israel are subconsciously and continuously present in these novels, the authors—some of Israel’s best known—are no less concerned with creating an Israel where belles-lettres and fine arts are moved from the background to the foreground of consciousness. This is in contradistinction to the “political Israel” we in America are so often presented with. Such is the case especially with the strong-willed character Atalia Abravanel Wald in Amos Oz’s Judas and outspoken Ruta Tavori in Meir Shalev’s Two She-Bears.

As to the men of Aharon Appelfeld and David Grossman, they reveal a deep-seated feminine side, where feelings and emotions play as important a role as actions. To a greater or lesser degree, this trend has to do with the ways Israeli literary artists today have learned to create, with psychological insight, compelling literary characters of both genders.

The year 1967, apparently, will always remain with us. But these novels suggest a process of integrating that historical experience into a different way of looking toward the future.

Judas

by Amos Oz. Translated by Nicholas de Lange (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 305 pp. $25)

Among the several ways to characterize the powerless main protagonist of Amos Oz’s new novel, unheroic hero, lost boy, schlemiel and lo yitzlach (loser) come readily to mind. Shmuel Ash is a dud, a gangly, bushy-bearded 25-year-old graduate student living, a decade after Israel’s War of Independence, in a Jerusalem divided by barbed wire, minefields and Jordanian snipers. He is writing his master’s thesis on “Jewish Views of Jesus,” a project that, despite reams of notes, is going nowhere. For every compelling point about the subject he uncovers, he finds an equally compelling counterpoint that turns his “work” into an act of pointlessness. He realizes that his main idea—that Judas Iscariot, the Christian world’s archetype for the hateful Jew in his so-called betrayal of Jesus, was the true founder of Christianity—will never gain traction.

There is even more gloominess in Shmuel’s life. His beloved has just married a bureaucrat who measures rainwater. The socialist café-revolutionaries he hangs around with have disbanded. In addition, his father, who has been underwriting Shmuel’s academic lifestyle, has just gone bankrupt, forcing his son to withdraw from university and find a job.

The job he finds could not be less heroic. He will be a part-time minder of Gershom Wald, a curmudgeonly, opinionated, housebound invalid. Shmuel’s main responsibility is to serve as the old man’s conversational sparring partner. Shmuel has been hired by Gershom’s daughter-in-law, Atalia, the attractive 45-year-old widow of the only real hero in the novel, Micha Wald, who was brutally massacred by Arab marauders during the 1948 war. Gershom, given shelter in Atalia’s home, spends his days on the telephone offering raging homilies to his old cronies. In the evening, Gershom talks with Shmuel about Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s fictional nemesis, an apostle of powerlessness, Shealtiel Abravanel. Shealtiel also happened to be Atalia’s deceased father and was adamantly opposed to the founding of a state in the Land of Israel. The tie that binds Shmuel to this household is that Shealtiel, like Judas, is castigated as a traitor.

In chapter 47, Judas speaks in a beautiful poem in prose that is a radiant work of art embedded in a gloomy context:

And when we arrived in Jerusalem, I made the crucifixion happen for him almost single-handedly.It occurred to no one in Jerusalem to crucify him. In the eyes of the Chief Priests this lad from Galilee was merely another feeble-minded preacher dressed in rags. Whereas for the Romans he was simply a demented beggar, sick with God like all the Jews.

This chapter is not unlike Michelangelo’s Pietà, a poster of which decorates Shmuel’s attic room. The chapter describes Judas’s state of mind as he contemplates hanging himself after a crucified Jesus proved not to be a god but a man of flesh and blood. Because there is neither a sentence introducing this chapter nor a transitional phrase at the end, readers are justified in conjecturing that it is meant to be taken as an excerpt from Shmuel’s forthcoming book, The Gospel According to Judas (the Hebrew title of Oz’s novel). If this is so, Shmuel Ash is not the lo yitzlach we had been led to believe.

A Horse Walks into a Bar

by David Grossman. Translated by Jessica Cohen (Knopf, 208 pp. $24.95)

In his 1956 novel, The Fall, Albert Camus took readers into a bar in a squalid section of Amsterdam where Dutch Jews had lived before the Holocaust. There, a former high-end Parisian lawyer, now a seedy “judge-penitent,” holds court nightly, confronting the humans who walk into the bar. Confessing his own sins, he seeks to induce his “clients” to take possession of their own—and history’s—transgressions. Now, 60 years later, writer David Grossman, in A Horse Walks Into a Bar, provides an Israeli update to the European setting and, in so doing, turns Camus’ Christian “confession” into a Vidui, the traditional Jewish confession recited by the dying as well as on Yom Kippur.

Grossman does this by taking his readers into a rundown nightclub in a squalid section of Netanya for a performance by a stand-up comedian who has other things on his mind than telling the lame jokes—often vulgar and insulting—that this genre of entertainment calls for.

The performer, Dov Greenstein, whose stage name is “Dovaleh G,” has summoned a different type of high-end lawyer—a disgraced judge, in fact—to come and “judge” his performance, not as a comedian but as a human being. The judge, Avishai, is a former classmate.

The novel, written without any chapter divisions, is presented as a two-hour monologue interspersed with Avishai’s unspoken commentary on the comedian’s gloomy tale. There are also raucous interruptions by members of the audience. Among the compassionate ones who stay—fascinated by the depressing melancholy being meted out—is a short woman whom Dov calls Pitzaleh (Yiddish for “tiny one”) and, even more meanly, Thumbelina. Having grown up in Dov’s Jerusalem neighborhood and remembering him as a quirky boy who walked on his hands, Pitzaleh, who shows herself to have strong convictions, denies Dov’s claim that he was ill behaved. Neither she nor Avishai knows, however, that Dov was the child of an abusive father and a Holocaust-survivor mother awash in vulnerabilities.

The protracted tale of Dov’s greatest psychological trauma takes up the second half of the book, where we also learn, told in counterpoint to Dov’s performance, the vicissitudes of the life of the repentant judge, including a tragic love story and a breakdown.

Curiously, among the jokes that Dov feels he owes his audience—the one that comes from the novel’s title—is begun but interrupted constantly by zany digressions and never completed. While it would be reviewer malpractice to reveal all the subtle secrets and mysteries hidden in this novel—for example, that Dov’s vulgarity masks his erudition—it certainly couldn’t hurt to tell the title joke: A horse walks into a bar. The bartender looks up, sees the horse, and says,“Why the long face?” By the time commiserating readers who have stayed to the end of this thought-provoking novel look up, they will have understood why indeed the long face.

Two She-Bears

by Meir Shalev. Translated by Stuart Schoffman (Schocken Books, 320 pp. $26.95)

Meir Shalev has already given us, among other delightful reading experiences, the tender A Pigeon and a Boy and a feel-good family memoir, My Russian Grandmother and Her American Vacuum Cleaner. Two She-Bears, an alluring novel wrapped in matters of life and death, has its source in the enchanting yet civilizing world of Hebrew grammar. The Hebrew title of the novel, Shetayim Dubim, a puzzling Hebrew construction seemingly confusing masculine and feminine, is taken from a Bible story that, like this novel, involves wanton killing. The opening chapter of the book consists of a phone conversation between two murderers—one a “plain-speaking” Israeli with sloppy speech habits; the other, his refined, grammatically correct employer who will not tolerate improper use of Hebrew.

The language conundrum is presented in the life and classes of Ruta Tavori, a high school teacher of Bible stories in an agricultural settlement. Ruta, a descendant of the founders of the moshava, is no stranger to death and murder and is skilled in recounting the founders’ tales. One day, a scholar doing research on gender issues in the Baron de Rothschild’s settlements lands at Ruta’s door. Ruta has long thought about gender issues in Israel and suffered tragically from them. Moreover, Ruta, a woman with literary talents, burns with the desire to reveal not only her own story but also the moshava’s. Ruta chastises the neighbor whose father bore false witness to the murder around which her story revolves.

My grandfather was once a violent man, cruel, primitive. He became a human being only after he brought me and Dovik [her brother] here. We were his tikkun, his correction, atonement.… But your grandfather was a louse and remained one to his dying day.

In addition to telling of the modern rebuilding of the Land of Israel, she also goes about restructuring the story of the human race and its evolution from the animal kingdom, demystifying the notion of the noble savage in the process.

There are two main male characters in Ruta’s story: Ze’ev Tavori, her imperious grandfather, and Eitan Druckman, her husband, who so loves both Ze’ev and Ruta that he takes on the Tavori name. From a distance, Ze’ev is a naturalist who loves to go out into the fields to collect seeds and identify flowers and trees. His murderous attitudes toward human beings—including his adulterous wife, her lover and their infant daughter—are governed by other primitive instincts, including manly honor and loyalty to clan. Eitan, the muscular Zionist hero, is seduced by Ze’ev’s brutal certitudes and becomes a worshiping acolyte who softens only in Ruta’s company. When Eitan tries to inculcate in their 6-year-old son the masculine arts that one needs to become a Tavori man, disaster strikes in the form of a deadly snakebite. Eitan will retreat from humanity with a primitive vengeance. Ruta’s tale of the revenge killings Eitan commits mirrors those of the detective-story beginnings of the novel.

And what of Ruta? In the end, she will be able to shine a thin ray of light into the dark cave that is this somber but engaging novel. What is the cost of this ray of light? That is Meir Shalev’s unanswered question.

The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping

by Aharon Appelfeld. Translated by Jeffrey M. Green (Schocken Books, 288 pp. $26)

Aharon Appelfeld’s novel The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping can be traced back to his 1981 groundbreaking masterpiece, The Age of Wonders. The earlier book dealt with failed artists in pre-Holocaust Europe: a musician, a painter and, above all, the narrator’s bitterly unsuccessful father, an author destroyed by society’s anti-Semitism and by his own hatred of petit-bourgeois Jewry. The narrator (first called Bruno, then Erwin) had escaped the Holocaust to become a writer in Israel and later returns to his childhood home in Austria, seeking, unsuccessfully, to make sense of his unconventional literary accomplishments.

Twenty-five years after writing The Age of Wonders, Appelfeld returns us in the new novel to the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust in the person of a redacted Erwin, a teenager who has joined a group of refugees recruited by Youth Aliyah to prepare themselves to become the “New Jew” in Palestine. Erwin stands apart from the others by succumbing to a chronic strain of sleeping sickness, as he wends his way through Europe and from there to the British-run Atlit detention camp in Palestine and, subsequently, to a fictional Kibbutz Misgav Yitzhak. There, even as he is being trained to become a soldier, he sleeps—and dreams. At first glance, what he dreams about is vintage Appelfeld—the city of his birth, his assimilated family and the idyllic countryside abode of his grandparents in the Carpathian Mountains.

While Erwin sleeps, he speaks to his dead parents as though they were alive in the present.

The shift from memory to creativity takes place after Erwin has been seriously wounded in a military action and has become a recuperating invalid. Here, the novel revisits and revises the story in The Age of Wonders, when Erwin meets a former teacher, Dr. Weingarten, who had survived the death camps. The teacher reports to the son that his father, far from being the scoundrel and literary failure he was in the earlier novel, was the hero of the concentration camp where he was imprisoned and used storytelling to raise the spirits of his fellow victims.

After reading two of his books, I sensed that he had great talent, but it seemed tangled up; I hoped that someday he would emerge from this entanglement. I didn’t absorb the logic of his sentences. Only when he was telling us stories at night did I feel he was conveying brilliant depths to us.

This reading of the novel suggests that the entire corpus of Appelfeld’s writing is a continuous act of revising and rewriting. By constantly recasting the stories he has created over a long career, Appelfeld creates a literary way of bringing his pre-Holocaust past into his Israeli present. There is no longer a need to return to Bukovina in Ukraine. There is a creative way of bringing Bukovina to the café in Beit Ticho in Jerusalem where the venerable and venerated Appelfeld comes to sit and write.

Joseph Lowin is the author of the recent book, Art and the Artist in the Contemporary Israel Noveli, which is a study of eight Israeli masterpieces.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply