American View

Feature

Love Letters: A Lost Writing Genre

When Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso and storyteller Peninnah Schram were collecting love stories for their new book, Jewish Stories of Love and Marriage: Folktales, Legends, and Letters (Rowman & Littlefield), on which this article is based, they found a treasure-trove of love letters. The letter writers were a diverse group—high-powered intellectuals and community leaders as well as military couples, even the authors’ own parents. All, however, expressed heartfelt longing and affection.

Sandy Eisenberg Sasso: A bride-to-be whose wedding I was officiating called me with a special request. She asked if during the wedding ceremony I would be willing to read from one of the letters that her maternal grandfather had written to her grandmother 58 years ago. The next time we met, she handed me a plastic bag filled with handwritten letters. I started reading and couldn’t stop.

That night over glasses of red wine, I read from my favorites to my husband, Dennis. The following excerpt was written a few months before the bride’s grandparents married, when her grandfather was away working at a summer job:

Darling, I love you so much…. When I feel low or blue all I have to do is to pick up…your letters and reread them and everything seems all right again. I only wish, baby, you were here to kiss me.… There is only one thing I want on this earth and that is you and your love. The only job I ever want is making love to you and (loving) our kids and I will sacrifice everything including my life for that objective. Good night, my darling. May the good Lord keep you safe and sound in my absence.

Though less of a romantic than I, Dennis was still moved. I wondered why we hadn’t written each other such letters. We got engaged in 1970 while studying the book of Jeremiah. The prophet is most known for his preaching against sin and predicting disaster—not the most conducive text for a marriage proposal—though chapter 31 contains the passage, “with eternal love, have I loved you.” We engraved the 14 Hebrew characters of that 2,700-year-old sentiment inside our wedding bands. “Those are my letters to you,” Dennis reminded me.

The young bride had brought me her grandfather’s letters at a fortuitous time. Peninnah Schram and I were working on a book on Jewish love and were planning to include biblical and rabbinic narratives, Jewish folktales from around the world and contemporary stories.

We realized then what was missing—love letters. Over the course of our research, we learned of the Jewish custom of a bride and groom writing letters to one another prevalent in Eastern Europe and America, especially in the late 19th and 20th centuries, and discovered a precious collection of writing.

We were also motivated to find letters in our own families. My parents, Freda and Israel (Irv) Eisenberg, were married in 1946. I asked my mom if my father had sent her love letters when he was a soldier in France during the war; she responded with a smile. “Yes, he sent lots of them. He knew that they were being censored, but he still wrote me as often as he could. He told me he loved me.” My father died when he was 64, and my mother was in her late 80s when I asked about the letters. I had hoped for a theatrical moment when my mom would gently lift a neatly tied package of yellowed papers from a mahogany box. Alas, she had lost the letters during one of several moves. Up to my mother’s death last December at 95, she never stopped dreaming about my father.

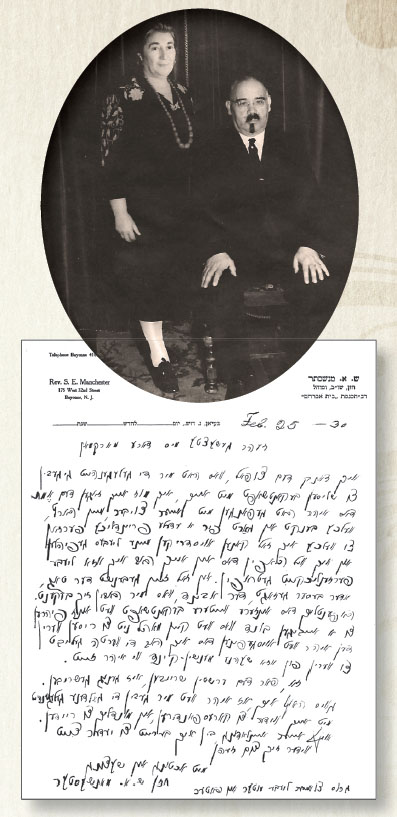

Peninnah Schram: I came across a bundle of letters while closing up my parents’ Victorian home in New London, Conn. It was 1978. My mother had died that December and my father eight years earlier. Going through a credenza, I saw a packet wrapped in a man’s large white handkerchief and bound with a shoelace. As I unwrapped it, I immediately recognized my father’s beautiful handwriting. This letter to my mother, written on February 25, 1930, just after they met, was originally in Yiddish.

Very respected Miss Dora Markman,

I am thankful for the opportunity that was presented to me to be able to make your acquaintance.

I must tell you the truth…that you, with your magic, found your way to my heart…. And the day should be blessed—or better said that the evening should be blessed—when we met each other.

Hazzan S.E. Manchester

The moment I saw the distinctive penmanship, I wept tears of joy and of loss. I recalled the midrash that recounted our ancestor Joseph inquiring of his brothers about their father’s welfare, and Judah handing him a letter written by Jacob intended for the Egyptian overseer. Seeing his father’s handwriting caused Joseph to weep. Jacob’s handwriting, not just his words, triggered evocative memories.

Sandy: Peninnah and I were excited to find the correspondence of German-born Marcus M. Spiegel and Caroline Frances Hamlin Spiegel, a Quaker who converted to Judaism, dating back to the Civil War. Marcus, an abolitionist, achieved one the highest ranks of any Jewish officer in the Union Army, becoming a colonel in 1863. On the first birthday of their fourth child, Marcus wrote to Caroline:

I would love to be with you tonight; I know and feel you are just now thinking of me, but will have to wait awhile, trusting that Vicksburg will soon fall. With hearty prayers for your welfare and that of our beloved children, I remain to the best and loveliest wife in the world a true and loving husband. You don’t know how much I love you.

Tragically, in May 1864, about a year after writing the letter, Marcus, 34, was shot and killed. Two months after his death, Caroline gave birth to their fifth child. She remained committed to Judaism, raising her family in the Chicago Jewish community.

The collection of love letters between Captain Alfred Dreyfus and Lucie Eugénie Hadamard Dreyfus may be familiar to some, as they have been exhibited over the years. A Jewish soldier in the French army, Alfred was falsely accused of treason in 1894 and sentenced to life imprisonment. At first, he wrote letters to Lucie in a diary that he never sent; that later changed and the couple was able to comfort each other during those dark years through their letters. Here is an excerpt dated January 31, 1895, written by Alfred:

…I have each day had a moment of happiness in receiving your letter. It was an echo of home—an echo of the sympathy of you all. That warmed my frozen heart. I read and re-read your letters. I absorbed each word. Little by little the written words were transformed and found a voice; it seemed to me that I could hear you speaking and that you were very close to me. Oh, the exquisite music that whispered to my soul.

Dreyfus was cleared of all charges in 1906 and reinstated in the military.

Rabbi Isaac Mayer wise was another romantic. Born in the Austrian Empire in the early 19th century, he immigrated to America in 1846. In Cincinnati, he established the institutions of Reform Judaism—including the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the Hebrew Union College and the Central Conference of American Rabbis. He and his first wife, Theresa Bloch, had 10 children before she died in 1874. Two years later, he married Selma Bondi and the couple had four children. His letters to Selma remind us that sometimes it is possible to find love after loss:

I go to sleep with you and wake with you, I kiss you 10 times a day, I dream about you day and night and still you want to know whether I think of you a little bit? I say: No. Because it would be high treason to think of you a little bit, Selma. My sweet dreamer: I cannot love a little…. I love you wholeheartedly and that’s how I think of you and how I long for you…. I will pour so much fire into your soul that you shall sing about love and praise it like Sulamith in the Song of Songs.

Peninnah: Today, people seem to have lost the art of letter writing. We believe that the faster and shorter the communication, the better. Emojis and emoticons attempt to take the place of richly embroidered romantic poetry. A contemporary text message might read: ILY (I love you). Thinking of you, I get TIME (tears in my eyes). Sending HAK (hugs and kisses). YLM (you love me)?

Waiting for a text message cannot replace the anticipation of receiving a hand-addressed letter. When I was traveling for nine weeks in Europe in the summer of 1958, my fiancé told me that he would write and send the letters to the American Express offices in cities I was visiting. The first place I always stopped was that office and, with a beating heart, asked if I had received any mail. How happy I was when I was handed a letter or two from Irv Schram, handwritten with longing and love. I carried those letters with me, re-reading them, touching the handwriting, smelling the paper with a joy that cannot be matched by reading a digital device.

Sandy: after discovering all these letters, I decided to ask the couples I have the privilege of marrying to write letters to one another before their wedding. I suggest that they return to those letters at each anniversary to recall what first made them fall in love.

When the bride stood under the huppah in the garden of her paternal grandparents’ home, I read the following from her maternal grandfather’s letters to his beloved:

Before I fell in love with you my darling, I always thought I could live only for myself. However…I have found out how wonderful life can be when one lives because of another’s love.

All of the love letters that we have uncovered in our research, and all that have been written throughout the centuries, connect us to the deeply human side of a loving heart engraved by hand. It is an honor to hear one soul speaking to another.

Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, the first woman ordained by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, is rabbi emerita of Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis. The author of award-winning children’s books, she is director of the Religion, Spirituality and the Arts Initiative at Butler University in Indianapolis.

Storyteller Peninnah Schram is professor emerita at Yeshiva University in New York. The author of 13 books of Jewish folktales, she is the recipient of a distinguished Covenant Award for Outstanding Educator and the National Storytelling Network’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Sheryl Stern says

Thank you so much for this article.

I have the love letters that my grandfather Hyman Lerner wrote to my Bubby Ethel Ayon written in the early 1920’s. I also have love letters written by my father Harry Moises to my mother Ann Lerner write in the early 1940’s. I kept a written journal of the dates I had with my husband-to-be Eddie Stern written in the 1960’s. The memories are so precious. They are also a snapshot of the history of their time.

I also have letters written in Yiddish from my Buby’s niece Yuhudit Poznaik Freund, who immigrated from Poland to Palestine in 1932. Her son Eytan and I continued the letter writing. I have followed in the footsteps of my ancestors. I still love to write 10-page letters by hand.

For the past twenty years I have been researching and writing my Family’s history. These love letters

are are such a special part of our family’s history. By reading these letters my ancestors come alive.

I learn about their character, their personality, their values, and through their love letters, I feel the love they shared with each other.

Thank you again for shedding light on this meaningful form of correspondence.

Sheryl Stern