Arts

Film

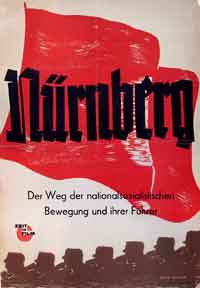

Nuremberg—Its Lesson for Today

On October 13, more than 2,000 Guatemalans packed the Teatro Nacional in Guatemala City to see the 2009 Sandra Schulberg–Josh Waletzky restoration of the 1948 documentaryNuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, which opened last September in New York to rave reviews and is currently on a worldwide tour. For the Guatemalans, the film resonated because of the atrocities their own country endured in the early 1980s. Although the 1948 film was the official United States documentary about the Great War Criminals Trial in Nuremberg, until this year, it was only shown in German theaters.

For the first time in history—from November 1945 to October 1946—leaders of a Western nation were held to personal account for war crimes they had committed in the name of a state. The Nuremberg trial was so unique that Justice Robert Jackson, its architect and chief United States prosecutor, had the trial captured on film so that it would serve as a warning to future generations. The American government commissioned a documentary to be made about the trial, to show to a battered postwar world.

Under the auspices of the United States War Department and with direct input from Jackson, director Stuart Schulberg completed the documentary, which he entitled Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, in 1948. The film is organized around the four counts of the indictment against the Nazis and reconstructs the prosecution’s case as it unfolded during the trial, using film evidence presented in court as well as live trial footage. The film uses footage from evidentiary films that were presented at the Nuremberg trial. The result is a film that is at once shocking and intellectual, dispassionate and full of fury.

Nuremberg was shown throughout Germany in ’48 and ’49, giving viewers their first glimpse of what had actually taken place during the war. In preparation for the film’s distribution in America, Schulberg showed it to higher-ups at the War and State Departments. Without apparent explanation, officials decided that the film would not be released to American theaters. An outraged press protested, but to no avail. The Army quashed both the film and the reasons behind its suppression. (Speculation for the reasons include that the film was scheduled for release in the United States just as the Marshall Plan was being put into action, and the American Army felt the public wouldn’t support the plan if they saw the film; as of the film’s release date, the Soviets were no longer our allies, a relationship contradicted by the film; a number of Army officials objected to the fact that soldiers were denied the right to claim they were just following orders. In addition, there was a great deal of conflict between the American Military Government in Berlin and the War Department in Washington over who would control production of the film.)

Nearly 60 years after Schulberg’s fateful meeting with the military, his daughter, Sandra Schulberg, found a print of the film in a corner cupboard in the family home. Then she found the documentation about its suppression. “When I heard that this film had never been released here, that the negative was lost, that it was buried all these years, I really felt it was a duty to restore it and bring it back,” she says.

As Schulberg didn’t want to change a frame of film, restoration in this case meant rebuilding the sound track. The original narration paraphrased what was being said in court; Schulberg wanted the audience to hear Jackson deliver the opening and closing himself and the defendants deliver their own denials. That involved not only the painstaking job of synchronizing sound to film but also re-recording the narrative track (delivered by Liev Schreiber in the restoration) and re-constructing sections of the musical track that could be integrated with the original.

As Schulberg didn’t want to change a frame of film, restoration in this case meant rebuilding the sound track. The original narration paraphrased what was being said in court; Schulberg wanted the audience to hear Jackson deliver the opening and closing himself and the defendants deliver their own denials. That involved not only the painstaking job of synchronizing sound to film but also re-recording the narrative track (delivered by Liev Schreiber in the restoration) and re-constructing sections of the musical track that could be integrated with the original.

The Schulberg–Waletzky restoration has ignited viewers’ passions. It is Sandra’s hope that screenings will be followed by panel discussions, as they have been in New York, where panelists have included Benjamin Ferencz, chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trial of the Nazi Einsatzgruppen; Auschwitz survivor Ernest Michel, who served at the Nuremberg trial as a press correspondent for German newspapers (see interview); and Ambassador Stephen Rapp, ambassador-at-large on War Crimes issues, who speaks about the case law developed at Nuremberg as the foundation of today’s International Criminal Court.

Schulberg is currently promoting the film as well as working on a scholar’s edition DVD. Noting that the movie’s subtitle—Its Lesson for Today—was crafted in 1948, Schulberg reiterates its relevance for modern audiences: “This is a great antiwar film,” she says. Most viewers will agree with her.

For a schedule of national and international screening of the film, go to www.nurembergfilm.org.

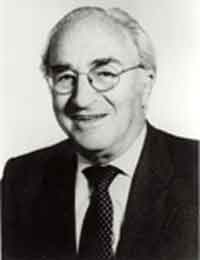

Nuremberg Eyewitness: Ernest W. Michel

As it was getting dark, Ernest W. Michel crept into the forest with two of his friends. They waited till they were sure all was quiet, then slowly sneaked deeper and deeper into the woods. When he could only faintly hear the Nazis ordering their prisoners to continue on their death march, Michel ran through the trees until he was free for the first time after six years imprisonment in Paderborn, Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

Seven months later, Michel—who had been kicked out of school at the age of 13 for being Jewish and whose parents had been selected for death as soon as they had entered the gates at Auschwitz—ascended to the press gallery to take his place beside Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite at the Great War Criminals Trial at Nuremberg. Michel had been hired as a reporter by DANA, the newly formed German press agency, and had gotten the Nuremberg assignment.

“The first time I come into the press gallery, 25 feet away from me sits Hermann Goering,” Michel recalls. “I felt like jumping down and screaming, ‘Why did you do this to me? Why did you kill my parents?’ But obviously I couldn’t do that, so I ate it on the inside.”

For eight months, he published under the byline “Ernest Michel, DANA Staff Correspondent (formerly prisoner No. 104995 at Auschwitz concentration camp).”

In the camps, Michel had made a vow to his parents and his friend Walter, who had not escaped: He would bear witness to the horrors he had survived so that no one would ever have to face them again. For the next 60 years, from his reporting job in a tiny town in Michigan to his position as executive vice president of UJA-Federation in New York, from organizing The World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem to writing an autobiography, entitled Promises Kept: One Man’s Journey Against Incredible Odds (Barricade Books), he spoke out again and again.

One of those speaking engagements was at the New York Film Festival press screening ofNuremberg: Its Lesson for Today. It was the second time the 87-year-old Michel had seen the film, and he was so moved that he was visibly shaking. In the foreword to Promises Kept, author Leon Uris writes, “Ernie Michel was chosen to live by a force beyond his own power.” Perhaps, but perhaps it was Mr. Michel who forced himself to live even beyond his own power, continued to speak out even though it made him tremble six decades after the fact. —J.G.M.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply