Arts

Exhibit

Eastern Exposure

All images courtesy of the Museum of Jewish Heritage, NY

“Three Crak!” “Pung!” “Four Bam!”

If these cries sound to you like bubbled comic-book punches, you are not from the generations of American Jewish women for whom the exclamatory plays of Mah Jongg elicit shivers of memory and delight. A new exhibit at New York City’s Museum of Jewish Heritage (646-437-4200;www.mjhnyc.com) not only highlights the intriguing objects, colorful imagery and history of the game but also explores its place as a potent vehicle for identity, community and philanthropy. “Project Mah Jongg” runs through February 27, 2011, then travels to Jewish museums throughout the country.

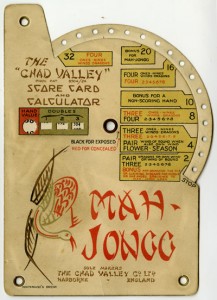

Eighteen panels patterned as giant Mah Jongg tiles, with their signature dragons and dots, bams (bamboo), flowers and crak (characters) symbols, fan out above six cases filled with sets of all kinds; bamboo, bone, and cardboard tiles, artifacts and memorabilia. A central table draws visitors to play an actual game, their memories activated by the visceral clacking and feel of the tiles. Audio recordings of games and memories are interspersed among historical photographs and contemporary illustrations. “Mah Jongg is a visual universe unto itself,” says exhibit designer Abbot Miller. “It was—and still is—a social media with a heavy dose of style and history.”

According to curator Melissa Martens, Mah Jongg tells a riveting story of immigration and cultural adaptation. Introduced to American audiences in 1922 by Joseph P. Babcock, a representative of the Standard Oil Company in Suzhou, China, Mah Jongg evolved from Chinese cards and dominoes based on money symbols and swept the United States over the next three years. Companies like Abercrombie & Fitch, Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers marketed affordable games under different, trademarked names that imagined exotic and elusive origins; each claimed to be the most authentic: “If it isn’t marked Pung Wu it isn’t genuine,” claims one manufacturer. “The set with the real dragons,” announces a Pung-Chow set. “The royal game of China/Played for thousands of years in the land of Confucius,” declares Pung Wo Junior.

An American taste for Chinoiserie was already fashionable. A postcard (circa 1910) depicting the main floor of Vantine’s, an importer of Asian goods, brims with colorful hanging lamps and display cases. Though not exclusively a women’s game, those with time and money to spare were the first to embrace Mah Jongg, which became an index of “stylishness and sophistication,” Martens writes in the accompanying catalog. In a 1924 Washington Post column, Mildred Holland suggests Mah Jongg as an “opportunity for displaying rings and bracelets…making the most of hands which are pretty in shape, texture, grace and grooming.” And, in fact, women showed up to play in fur collars, hats, buns and long dresses—but also attired in bathing suits, as a photo from 1924 of a floating Mah Jongg game printed in The Boston Globe indicates.

The “Mah Jongg Kid,” a novelty doll in orange pants, Chinese button-down top and black pigtail layers cozy associations onto this veneer of worldliness. Yet Mah Jongg provoked its own controversy as it became a game of mixed messages, says Martens, a receptacle for accusations of vice, gambling and wastefulness as well as accolades of virtue.

For Jewish women—at first primarily of German but later also from East European backgrounds—Mah Jongg was a “reminder of American inclusion, carrying high-class connotations,” says Martens, while it “drew heavily on Chinese imagery that reflected the plight of immigrants…. Encounters with Chinese products could stir both anxiety and empathy,” especially since the Jewish Lower East Side was contiguous to Chinatown. Though the fad peaked for the general public by 1925, Mah Jongg was just beginning to cement itself as an icon of American Jewish womanhood.

The leaders of the National Mah Jongg League, formed in 1937 to standardize the rules of game, were reportedly all Jewish. Early rulebooks written by Jewish women included Florence Irwin’s The Complete Mah Jongg Player. League founder Dorothy Meyerson even taught the game on television; a photo captures a 1951 show. The league opened chapters all over country, grew to thousands of members and articulated a philanthropic purpose. It prepared new and varied scorecards annually; examples are on display. (The league continues to sell about 300,000 to 400,000 cards a year, an annual pre-Passover ritual.)

The updated scorecards were sold through sisterhoods, Jewish women’s organizations and other groups to support charities selected by the members. Hadassah was designated numerous times; its medical unit in Palestine was an early recipient. In 1943, Hadassah’s Atlanta chapter raised funds for 850 children and 350 adults who arrived in Palestine. The league created a “national community,” says Martens, and Mah Jongg’s philanthropic goal eclipsed the negative images. “Though the basic object of the league rotates around something as unimportant and trivial as a game…we have managed to find an objective that is not trivial,” the league’s president stated in 1941.

The war years heightened the need for togetherness and distraction and in its wake, Mah Jongg games continued to be an avenue to community and comfort, functioning as support groups where women could express child-rearing worries and just be themselves. A photogenic group in the Catskills relaxes, all smiles, in pointy sampans, berets, cowboy hats and headscarves. Food rituals often accompanied the games: A display showcases a 1950s apron, streamlined art deco dishes and boxes of Jello and Joyva Jell Rings that might have been served on them.

“We always had to serve pineapple with a cherry on it…chips, coffee and cake,” a woman recalls on one of the recordings in part of the exhibit. “My mother-in-law taught me to play,” says another woman. “I really can’t remember who taught me,” yet another confesses, “but I played obsessively two or three nights a week. The babysitter came at 7, and we played ‘til 1 or 2 in morning.”

“You make a connection with the people you play with and it’s lifelong,” says Ruth Unger, the league’s current president. “The bond goes from mother to daughter and friend to friend. It doesn’t get broken.”

Today, younger women who may have inherited sets from their mothers and grandmothers are intrigued by the game’s retro cachet, its social aspect and connection to family. Contemporary artists still find poetry in the game, and several reimaginings are shown in a special edition of 2wice Magazine titled “Mah Jongg: Crack, Bam, Dot” that was published in conjunction with the exhibit. Included in the publication are Bruce McCall illustration of Chinese elders passing along the ancient game to modern-day Miami women—a menora stands on a sideboard and wine and gefilte fish are set out on a cocktail table; fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi’s “Mah Jongg Collection,” which features a backless emerald-green evening gown and bathing suit, both with a flowing serpent print, a black lace-and-satin cocktail dress and a “day costume” with a tile print. Illustrator Maira Kalman concocts a “Mah Jongg Murder” cartoon, which ends with a trio of women looking out above a stabbed man in blue.

In “New York Mah Jongg,” which is in the exhibit, illustrator Christoph Niemann, mirrors the game’s strong Jewish associations. He merges Jewish symbols into the game’s distinctive visual language, replacing three dots with bagels; four dots with matza balls in soup, and one dot with a kippa. Bams become a menora and six dots become part of a Magen David. Mah Jongg’s Chinese origins are almost forgotten.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] Rahel. “Eastern Exposure.” Hadassah Magazine (January, […]