The Jewish Traveler

Panama, a Jewish Paradise Between Two Oceans

When most international travelers add the Central American country of Panama to their list of top destinations, it is most likely to behold, if not sail through, the engineering marvel that is the Panama Canal. In 2024 alone, more than 800,000 people visited the canal’s Miraflores Visitor Center, and local authorities expect the 2024-2025 cruise season to see more than 225 passenger ships transiting the canal, with some carrying upwards of 4,000 guests.

But Jewish travelers have further incentives to visit the lush tropical paradise—the country’s increasingly sophisticated kosher amenities, from high-end gourmet restaurants to hotels that cater to an observant clientele.

Indeed, in recent years, Orthodox social media influencers such as Gabriel Boxer (aka the “Kosher Guru”) and TikTok star Miriam Ezagui have documented the trendy kosher scene as well as excursions to the Monkey Island nature preserve, outdoor adventures like canoeing and cultural interactions with the indigenous Emberá community.

The evolution of Panama as a Jewish destination may be due to its status as the largest Jewish community in Central America. The country of more than four million is home to 10,000-plus Jews, most of whom identify as traditional or Orthodox, and boasts several synagogues, over 35 kosher restaurants and two large kosher supermarkets. The Panama Kosher Fest, held annually in January, seeks to highlight both kosher cuisine and local culture.

The abundance of kosher resources, unusual in a tropical setting, provides a foundation for indulgent vacations set amid palm trees, modern skyscrapers and the unique geography of being sandwiched between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

Panama City—the capital and home to most of the country’s Jewish population—is in the Eastern Standard Time Zone, so for those visiting from the East Coast, there’s no need to change clocks or deal with jetlag. And unlike an increasing number of foreign destinations, levels of antisemitism are insignificant.

“Panama as a country has been very good to the Jews,” said Max Harari, president of El Consejo Central Comunitario Hebreo de Panamá, or the Central Hebrew Community Council of Panama, which acts as an umbrella organization for the country’s Sephardi and Ashkenazi communities. And, in turn, “the Jewish community has been very much involved in the development of this country.”

Indeed, many local Jews have worked, and continue to prosper, in the fields of construction, real estate, trade and commerce, and Panama has had two Jewish presidents. Max Delvalle Maduro served as vice president from 1964 to 1968—with a one-week stint as acting president in April 1967—and his nephew, Eric Arturo Delvalle Cohen-Henriquez, was president from 1985 to 1988 while dictator and military officer Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno was Panama’s de facto ruler. The current mayor of Panama City, Mayer Mizrachi Matalon, is Jewish.

The Jewish presence in Panama dates to the early 1500s, with the arrival of Conversos escaping the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions, whose tentacles had reached the Americas. Many of these early Jewish settlers either assimilated or, if their faith was discovered in the New World, were forced to convert to Catholicism, resulting in no visible Jewish presence for several hundred years.

Jewish immigration to Panama resumed in the 19th century, when the Spanish Empire began to fracture and many of its former colonies declared independence. At the end of Spanish colonial rule in 1821, Panama became attached to a federation known as Gran Colombia, only becoming completely independent in 1903.

According to the World Jewish Congress, in the middle of the 19th century, a number of immigrants of Sephardi origin from the Caribbean region and a much smaller group of Ashkenazi from the Netherlands settled in Panama, attracted by economic developments such as the construction of the bi-oceanic railroad and the California Gold Rush, which had brought them west. A further influx of Sephardi Jews from the Caribbean led to the establishment of Panama’s first synagogue, Kol Shearith Israel, in 1876.

Today, Kol Shearith Israel is the only non-Orthodox synagogue in Panama. It is housed in a community center that was consecrated in 2006 in Panama City’s Costa del Este neighborhood.

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 continued to bring Jews seeking economic opportunities. After World War I, Sephardi Jews, many of Syrian origin, arrived after fleeing persecution and instability in the Middle East brought about by the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire.

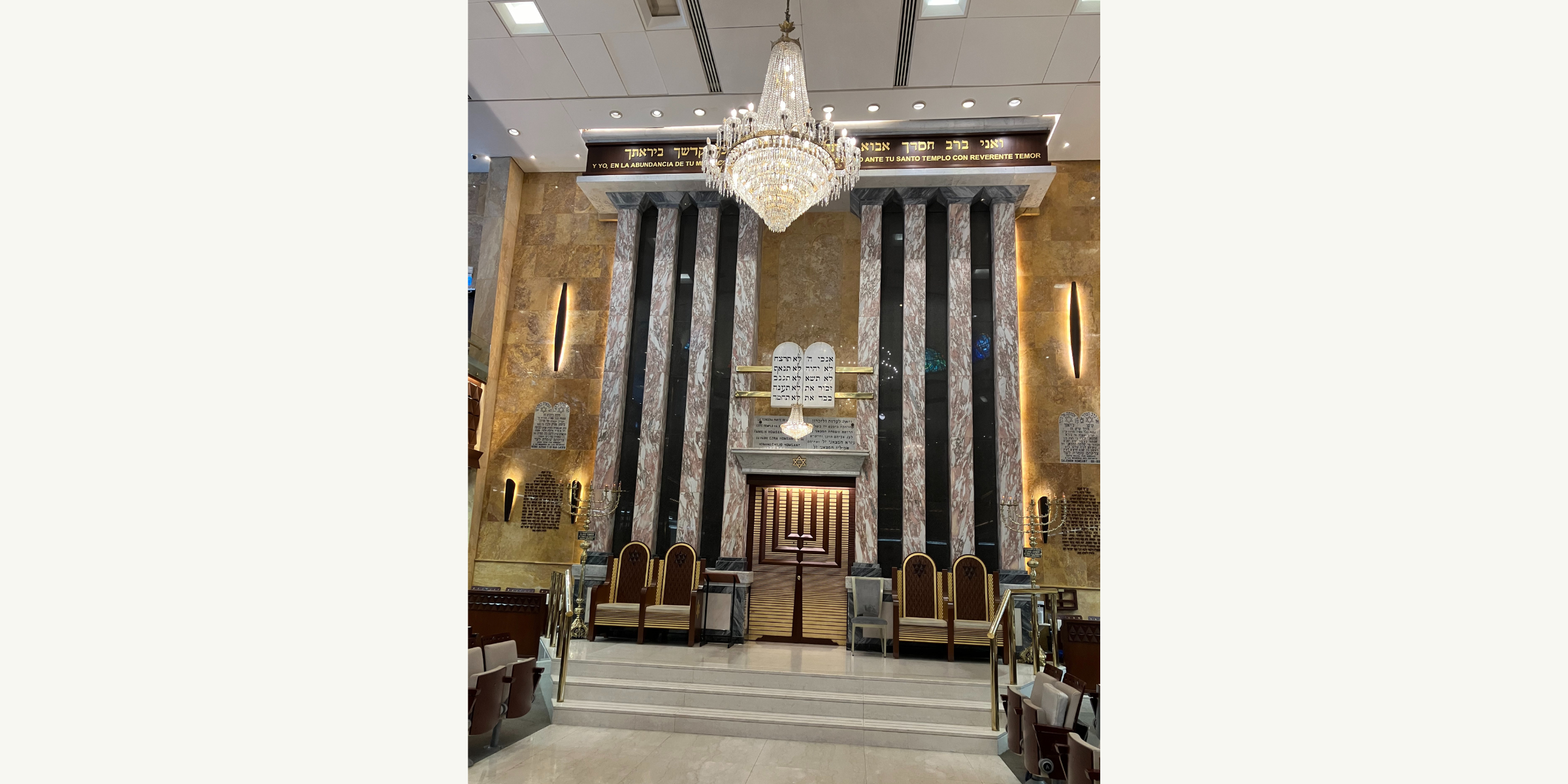

Another synagogue, Shevet Ahim, opened in 1933 to serve this Sephardi population. Based in Panama City’s Bella Vista neighborhood, the vast, ornately decorated synagogue maintains branches in other parts of the city, including Ahavat Sion in Punta Paitilla and Bet Max Ve Sarah in the Punta Pacifica neighborhood.

With the rise of Nazism in Europe, more Ashkenazi Jews began immigrating to Latin America, including Panama, in the 1930s and 1940s. Beth-El Synagogue, established in the 1940s, is today the only Ashkenazi synagogue in Panama City aside from two Chabad outposts.

Following World War II, Panama experienced further Jewish immigration as Jews from Arab countries were forced to flee their respective countries following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

Jews continue to immigrate to Panama, especially from the economically volatile nation of Venezuela as well as from Colombia and Argentina. Panama also draws American retirees to its tropical climate and comfortable, more affordable way of life.

Harari, the community president, said that Panama remains a safe place for Jews, and that there is no issue with wearing a kippah on the street, for example.

“We consider ourselves Panamanians,” said Harari, who estimates that the community today is 65 percent Sephardi and 35 percent Ashkenazi. His own car was decorated with Panamanian flags during this reporter’s meeting with him in December.

With several day schools in Panama City serving Jewish children from the Reform to ultra-Orthodox communities, “a huge majority of Jewish children have the privilege of having a Jewish education,” said David Mizrachi Fidanque, a former Jewish community leader.

And unlike in many smaller Diaspora communities, “a very large percentage of the children return here” after completing their university education, oftentimes abroad, Mizrachi Fidanque said.

Michael Harari, a cousin of Max, is a Shevet Ahim congregant who works in real estate property management. He is especially proud of the meaningful work of dozens of Jewish communal organizations, from local medical welfare groups and food pantries to Zionist groups like United Hatzalah, Keren Hayesod and Hadassah Panama, the national branch of Hadassah International. “Somehow, everyone is involved in one or another,” Harari said.

With the support of key philanthropists in Panama’s Jewish community, Hadassah Panama helped to fund the establishment of a major conference hall at Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem in Jerusalem. The Panama Auditorium has hosted hundreds of medical and scientific conferences featuring experts from around the world.

Indeed, support for Israel is evident to any observer visiting Panama City’s synagogues, where giant posters and signs in Spanish and English call for the return of all the Israeli hostages. There is also a somber, glass-encased art installation inside Shevet Ahim that pays tribute to the victims of the October 7 Hamas attacks.

IF YOU GO

• With over 35 kosher restaurants under the supervision of Shevet Ahim and two full-service kosher supermarkets, keeping kosher in Panama is a (tropical) breeze. Lists of kosher restaurants are available at Chabad Panama and Go Kosher Panama.

• Restaurants cover the spectrum of meat and dairy cuisines, with establishments like La Fonda Mi Reinita specializing in Panamanian dishes, such as chicken tamales; the whimsical garden vibes of Italian dairy restaurant Blame Kiki; and Yoss Burger, where you can order hearty meat entrees, including Israeli-style arayes—meat stuffed in a pita and then grilled—bursting with herbs and spices.

• Outside of Panama City, there are Chabad Houses in Boquete, in the West of the country, and in Bocas del Toro, along the Caribbean coast, which offer kosher options. On Shabbat, Chabad in Panama City offers prepaid communal Friday night dinners and lunches at its Punta Paitilla center. A few blocks away, the Beth-El Synagogue runs a prepaid kiddush luncheon.

• The Shabbat meal organization Fadalu, which means “welcome…come on in” in Arabic, provides home hospitality with a local Jewish family, most likely Sephardi, at no charge (donations are always welcome). Contact program coordinator Susie Antebi at Fadalupty@gmail.com for information.

• All visitors to synagogues and other Jewish institutions must complete a security screening in advance. Once you receive an emailed letter of acceptance, be sure to print out a copy to present to security guards, even for Shabbat services.

• Go Beyond and Panama Travel Co. offer customized kosher tours in Panama, from outdoor adventure trips to visits to Jewish communal institutions such as synagogues and schools.

• There are a host of upscale hotels in Panama City, from the centrally located Intercontinental Miramar overlooking the Bay of Panama, to the JW Marriott Panama in Punta Pacifica near several synagogues, to other top-name establishments like the Waldorf Astoria Panama, W Panama and Sortis hotels. In walking distance of many restaurants and synagogues in Punta Paitilla is Eshel Suites, which offers Shabbat-friendly conveniences like a keyless entrance, candles and grape juice.

• No trip to Panama is complete without a visit to the Panama Canal’s Miraflores Visitor Center. Not only will you see an incredible IMAX 3D film narrated by Morgan Freeman about the origins and building of the canal, but you can also watch ships passing through its locks. From Panama City, several operators run full- and partial-transit day cruises. For a deeper historical dive, David McCullough’s book, The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914, is a must read.

• Amador Causeway is a 3.7-mile road that connects Panama City to three islands, with amazing views of the city and the Pacific entrance to the canal. Along the way you will find the Biomuseo museum dedicated to country’s natural history, playgrounds, bike rental shops, kosher ice cream spots and one of the city’s two colorful “Panama” signs for taking pictures.

• Panama City’s Casco Viejo, or historic old quarter, dates back to 1673. Strolling through the UNESCO World Heritage site, you will see churches, squares, museums, cafes and many shops. When you are ready for dinner, stop at Lula, known for its kosher Israeli street food with a Latin flair, with an array of menu items like schnitzel, hummus and empanadas.

• To take a trip even further back in time, check out Panama Viejo, the remains of the first permanent European settlement on the Pacific Ocean and the country’s original capital, dating to 1519, that today is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. After wandering through the ruins, visitors can view an exhibit on crypto-Jews—those who maintained some level of secret Jewish practice—in the Plaza Mayor Museum Samuel Lewis García de Paredes.

Lori Silberman Brauner, former deputy managing editor at the New Jersey Jewish News, is currently working on a book about Diaspora Jewish communities.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply