Books

The Enduring Mythology of Anne Frank

More than any other work of literature, Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl helped the world comprehend the tragedy of the Holocaust. But in recent years, Anne’s name seems to be invoked more often in reference to forms of prejudice other than antisemitism. “Anne Frank today is a Syrian girl,” a New York Times columnist wrote during the refugee crisis of 2016. After the separation of families migrating to the United States made headlines during the first Trump administration, a director staged a version of the Broadway adaptation of the Diary using Latino actors.

Anne’s writing powerfully reminds us of the dangers inherent in any kind of ethnic, religious or racial hatred. But overgeneralizing this lesson risks implying that antisemitism is no longer a matter of concern, diminishing the special message her story bears about antisemitism’s enduringly destructive powers.

In the wake of the Hamas attacks on Israel on October 7 and Israel’s subsequent war in Gaza, Jews globally have experienced the effects of anti-Jewish hatred in a way that many believed was not possible in the post-Holocaust world. The violence in November against Jewish soccer fans in Amsterdam, the city where Anne spent almost all of her life, was a particularly acute reminder of the relevance of her story.

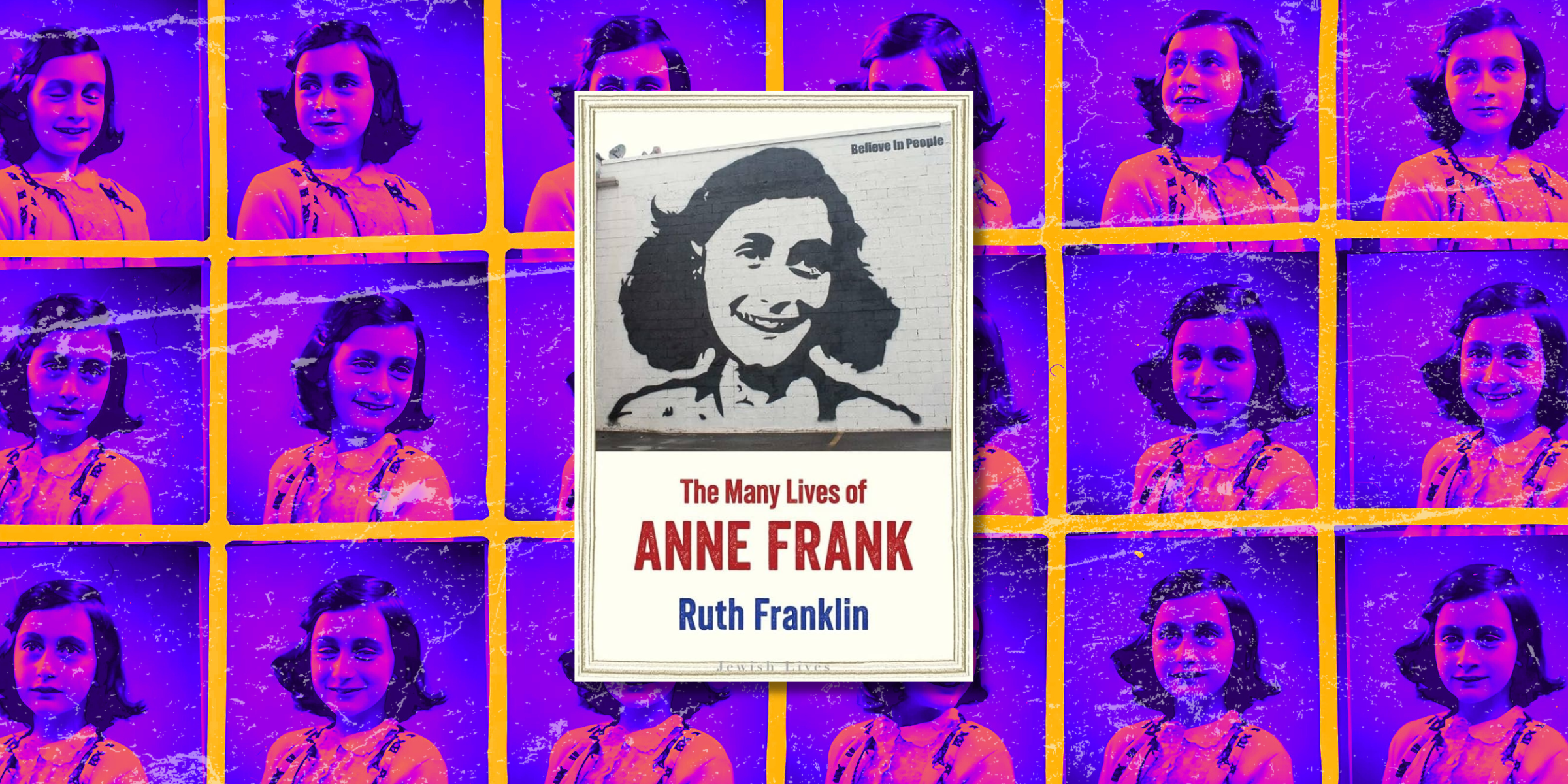

In The Many Lives of Anne Frank, I argue that Anne’s transformation into an icon has obscured our view of who she really was—a German Jewish girl growing up in the Netherlands who became a victim of Nazi persecution. As we mark the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz this January, Anne’s diary merits revisiting—not just as an inspiring tale of a girl coming of age under unimaginable circumstances, but as a siren alerting us to the malevolent potential of antisemitism anywhere.

They congregate on the plaza outside the entrance to Prinsengracht 263, beside a kiosk selling tickets for tours of Amsterdam and another offering traditional Dutch pancakes: children with school groups, teenagers sulking beside their parents, college students on a backpacking adventure, older couples who have saved up for a long-awaited European vacation. They come to the Anne Frank House from just about everywhere: the United States, Canada, Puerto Rico; England, Wales, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Spain, France, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Ukraine; Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Peru, Argentina; the Philippines, South Korea, Israel, Tunisia, Sierra Leone; Germany, so many from Germany.

Some take photos by the front door, striking a sexy or silly pose, and post the results on Instagram. If they happen to be there at the top of the hour, when the bells on the Westertoren clock, above the plaza, play their melancholy tune, they may look up in recognition, remembering how Anne wrote about that sound.

Many of them have come because of the Diary. They read it in school or on their own. They tried to picture Anne’s hiding place: the swinging bookcase, the steep stairs, the darkened rooms where she and her parents—together with the Van Pels family and the dentist Fritz Pfeffer—cooked and slept and studied and used the toilet and argued and listened to the radio and did everything that people do, never stepping outdoors, never seeing the sun.

The experience of visiting this space can be profoundly emotional. Many people comment on how much smaller it is than they expected. I first visited at age 8, after reading the Diary for the first time; little as I was, I found it impossibly cramped. Returning 40 years later, my body registered how rickety and steep the staircases were, set at such a narrow angle that I banged my knee while climbing up.

In 1952, after the Diary became a surprise best seller in the United States, Otto Frank, Anne’s father, found that tourists spontaneously appeared at Prinsengracht 263, which then still housed his business, wanting to see Anne’s “Secret Annex.” Otto used the proceeds from the enormously successful Broadway adaptation of the Diary and the movie version that followed to purchase and restore the building. In 1960, the year it opened, 6,000 people came. Within 30 years, that number had climbed to 300,000 per year.

Along with London’s Madame Tussauds and the Louvre in Paris, the Anne Frank House is one of the most popular museums in Europe, admitting some 70 tourists every 15 minutes, from 9 in the morning until 10 at night every day, including Christmas and New Year’s. At least as much as her diary, this building represents Anne to the world—a living monument in her name. But in the decades since her death, Anne Frank herself has become not just a person, but a symbol: a secret door that opens into a kaleidoscope of meanings, most of which her legions of fans understand incompletely, if at all.

Anne’s chronicle of the period she spent in hiding, now with more than 30 million copies in print in 70 languages, is the most famous work of literature to arise from the Holocaust. Since it first appeared in the Netherlands more than 75 years ago, Anne has become an icon. Time magazine included her on a list of the most important people of the 20th century. An asteroid discovered in 1942, the year she went into hiding, has been named after her. The horse chestnut tree in the courtyard behind the building, which Anne loved to gaze at through the attic window, died in 2010, but its saplings live on at museums and memorials around the world, including Manhattan’s Ground Zero.

Magazine Discussion: The Enduring Relevance of Anne Frank

Join us on Thursday, February 20 at 7 PM ET as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein hosts a discussion on the legacy of Anne Frank and her best-selling diary, which has been published in more than 70 languages.

Panelists include Ruth Franklin, author of the upcoming biography The Many Lives of Anne Frank, and Professor Doyle Stevick, executive director of the Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina and educational adviser to Anne Frank The Exhibition, which opens in January at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan and recreates the annex where Anne and her family hid in Amsterdam.

Her name is synonymous with courage, with resistance to persecution, with optimism. In Japan, it has also been used as a euphemism for a woman’s period. (Translated into Japanese in 1952, the Diary was one of the first books in that language explicitly to address menstruation.)

Anne’s face, smiling enigmatically from billboards worldwide and often accompanied by the most famous line from the Diary—“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”—has been compared to the Mona Lisa. Like that painting, her image evokes endless interpretations. Some see her as a little girl who dreamed of becoming a movie star and whose scribbled diary radiates goodness and hope. Others, including myself, have come to understand her as an accomplished and sophisticated writer—a self-conscious, literary witness to Nazi persecution who revised the rough draft of her writings into a polished work of testimony after hearing a Dutch government minister’s radio address calling for documents of the war years.

At the same time, Anne has often been a lightning rod for controversy. Some contemporary Holocaust educators believe that by virtue of its extreme popularity as a text—often the only text—from which children learn about the Holocaust, the Diary has crowded out other, more representative stories.

Critics have attacked the Broadway play and the movie based on it for downplaying Anne’s Jewishness and emphasizing the humanism in her writing. The play implies that the Diary concludes with her reflections on people being “good at heart.” But Anne wrote the famous line in July 1944, setting it just before a bleak passage that imagines the world gradually being turned into a wilderness: “I hear the ever-approaching thunder, which will destroy us too.”

Anne’s name has been invoked in service of a bewildering range of political causes in the intervening decades, from the United States civil rights movement to the boycott campaign against Israel. Some have argued that all these interpretations and reinterpretations constitute a betrayal of Anne, crowding out the essential aspect of her identity, namely that of a Jew persecuted by Hitler. As the Holocaust scholar Alvin Rosenfeld has pointed out, the Diary—which, of course, does not chronicle Anne’s miserable death from typhus at Bergen-Belsen—allows readers to feel they are accessing a Holocaust story without forcing them to confront its brutal reality. Instead, Anne has become a “symbol of moral and intellectual convenience,” with her affirmation of humanity’s goodness allowing her to be seen as an emblem of forgiveness and consolation rather than a tragic figure.

It is precisely this chameleon-like quality that has made Anne’s story uniquely enduring. As demonstrated by the comments that visitors to the Anne Frank House leave in the guest books, there is truly something in it for everyone. “Just like Anne wrote, we don’t have to wait, we can start to gradually change the world now, to fight for marginalized people and against the climate crisis,” a note from a visitor from Alaska reads. Some address her directly: “Thank you for writing about things that are painful but must be remembered so it does not happen again.” Visitors from Israel often write the phrase Am Yisrael Chai—“the people of Israel live.” Someone else has written, in Arabic, “I truly feel sorry for what happened to Anne Frank and her family, but what the Jews (Zionists) are doing to the Palestinians is much worse.” Another puts it simply, if crassly: “Great experience RIP Anne Frank.”

If Anne, as the journalist and historian Ian Buruma has written, has become “a ready-made icon for those who have turned the Holocaust into a kind of secular religion,” then her diary is akin to a saint’s relic: a text almost holy, not to be tampered with. This special aura around the Diary conflicts with the messiness of its reality as a text that exists in multiple versions and was edited by Anne herself as well as by her father.

It’s simpler to imagine it as a child’s “found object,” as the Dutch novelist Harry Mulisch called it—“a work of art made by life itself”—than to grapple with what the published version of Anne’s diary really is: a carefully conceived work of testimony to the persecution of the Dutch Jews. Recognizing and respecting Anne’s intentions as an author is a crucial first step in reclaiming her as a human being rather than a symbol.

In The Heroine with 1,001 Faces, the critic and scholar Maria Tatar brilliantly rewrites Joseph Campbell’s myth of the hero’s journey by asking how that framework might change if the archetypes it was based on were female instead of male. She notes that women, historically deprived of the weapons that gave men power, sought strength in storytelling.

Tatar considers Anne Frank as an example of the war heroine redefined, emphasizing Anne’s use of “words and stories not just as a therapeutic outlet for herself but also as a public platform for securing justice.” She insightfully notices the number of times Anne’s entries refer to acts of heroism in preserving “decency, integrity and hope” and credits her as a literary prodigy, putting her in the company of Mary Shelley, who wrote Frankenstein in her late teens.

But I’m also struck by the way Anne’s story re-enacts another mythological archetype: the woman who defies silencing. Its roots are found in the Greek myth of Philomela, a princess who is raped by her sister’s husband, Tereus. As Ovid recounts in the Metamorphoses, Tereus cut out Philomela’s tongue to prevent her from telling anyone what he did to her; she then took revenge by weaving a tapestry that revealed his crimes.

Anne might have been silenced by the Gestapo officers who invaded the annex, arrested her and the other residents and scattered her papers on the floor. But her story was preserved—first by two of the “helpers” who supported the family in hiding and found her papers after the raid, and then by her father—and disseminated far and wide, almost miraculously, as an account of trauma and persecution.

This powerful mythological resonance helps to explain the indelible imprint of Anne’s diary. But it also contributes to the difficulty in seeing Anne as the agent of her story rather than the object, the actor rather than the acted upon.

Anne Frank was not a helpless princess hidden away in an attic begging for rescue, but a brilliant young woman who seized control of her own narrative. Reimagining her that way requires a willingness to reconsider not just the facts of her life but also the way we understand heroism, both in her time and in ours.

Ruth Franklin, a book critic and biographer, is also the author of A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction and Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. This excerpt is adapted from her book, The Many Lives of Anne Frank, to be published January 27 by Yale University Press/Jewish Lives. Copyright © 2025 by Ruth Franklin. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] has brought the publication of Ruth Franklin’s The Many Lives of Anne Frank. You can find an adapted excerpt on the Hadassah magazine website, along with information about an upcoming (free) online event that […]