Arts

Bringing Anne Frank to New York City

Ronald Leopold has served as executive director of one of the most visited museum sites in Europe—the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam—since 2011. Now, in a move he sees as a “stand against antisemitism” and Holocaust denial, Leopold has brought the Anne Frank House to New York City with a full-scale recreation of the annex rooms where Frank, her family and four other Jews hid for two years.

“Anne Frank The Exhibition” is on display at the Center for Jewish History through the end of October, extended from the original April closing due to its popularity. The show takes visitors on a journey through Anne Frank’s life, set against the rise of the Nazi regime and the backdrop of World War II. The exhibition provides context for Anne’s experiences, beginning with her early years in Frankfurt followed by her family’s move to Amsterdam in 1934 to escape Nazi persecution, her arrest in 1944, her deportation to the Westerbork transit camp in the Netherlands and, later, to Auschwitz. The show concludes with the tragic end of Anne’s life at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany at the age of 15.

Leopold, 64, who lives in Amsterdam and lectures around the world on behalf of the museum, has called the Anne Frank House “the world’s most famous empty space”—haunted by the absence of the family that once lived there. He spoke to Hadassah Magazine a few weeks before the opening of the exhibition in New York City on January 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What inspired you to stage this exhibition to New York City?

We realized that many people are unable to travel to Amsterdam, and even if they are able to come, they might have difficulties getting tickets to the house. So we’ve been thinking for a long time about what we could offer those audiences who cannot visit the house. And, obviously, during the pandemic, that became even more of a problem. We began to think about how we could bring this story to audiences across the world.

Why is this an important time to present this exhibition?

With ever fewer Holocaust survivors in our communities, I think the responsibility of the Anne Frank House has never been greater. This exhibition is, in part, a response to this responsibility.

How will the objects on display—including a few documents that have never been seen before—shed new light on Anne and her family?

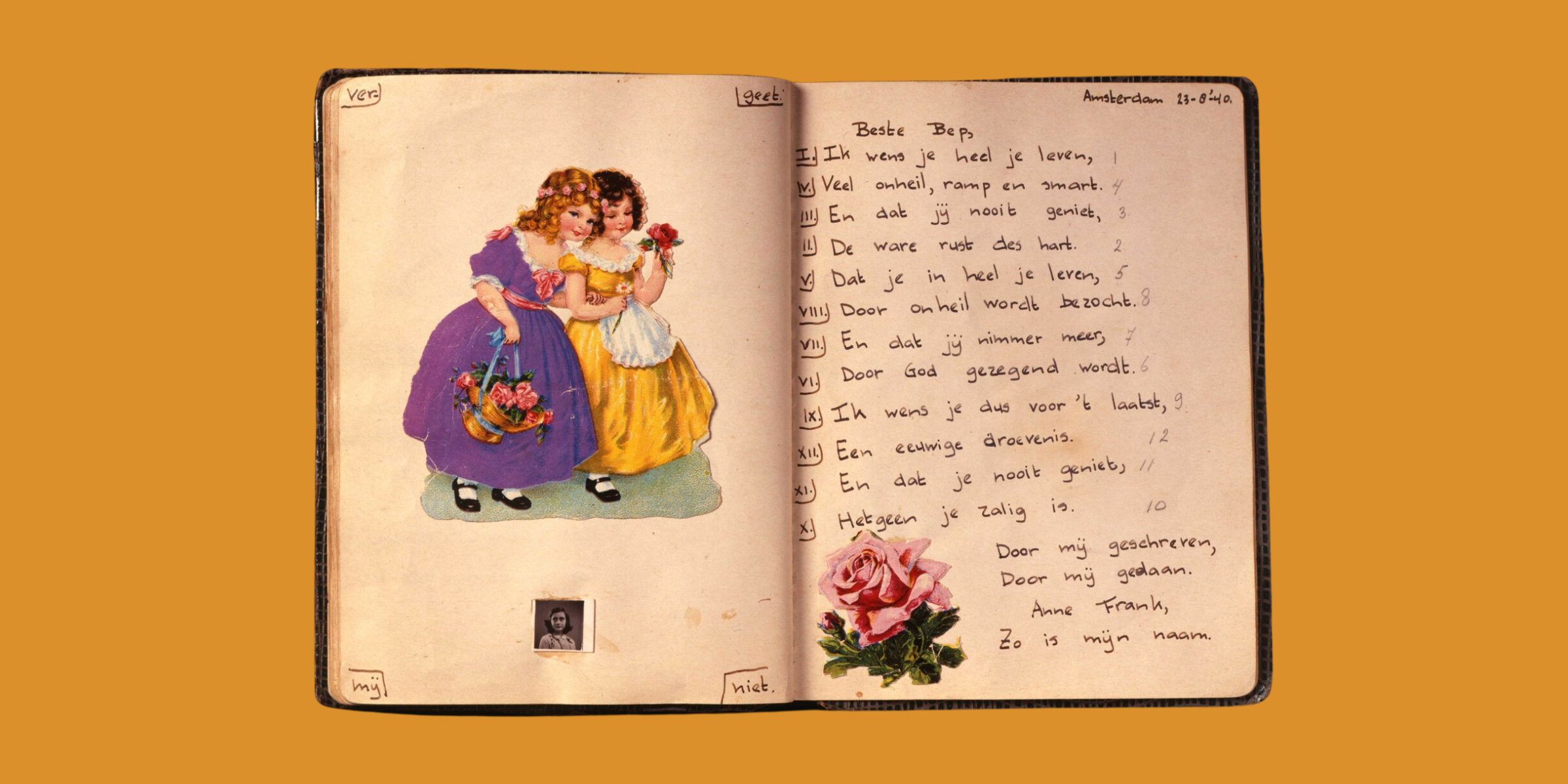

What we hope is that the more than 100 artifacts will contribute to a deeply personal connection between visitors and Anne Frank’s story. They show us a teenage girl, radiating life, embracing life, full of dreams, full of fear, of course, but also in a very intimate way. Just look at the beautiful, handwritten verse that she writes in an album of her dearest friend. With such an artifact, you can create a very intimate relationship between the visitor and the story.

How does the exhibition differ from the actual annex rooms in the Anne Frank House?

What’s different is that the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is unfurnished, and in New York, we will present a hiding place that’s been furnished. The original furniture in the house has been lost. But we know partly from Anne’s father, Otto, exactly what their hiding place looked like. And that’s an important source of information for us, which we use now to furnish this replica in New York City.

Who is the intended audience for this exhibition?

It’s been designed for all kinds of visitors, but specifically geared to young visitors. We think it’s incredibly important for a new generation to learn about Anne Frank.

Will this exhibition travel?

Once we complete a successful presentation in New York, our intention is to have the exhibition travel across the United States. We expect to make a decision on future plans after we have seen how people respond to it in New York.

What changes have you observed in your 14 years at the Anne Frank House?

What never changed is the interest in the story of Anne. As the distance in time increased from the end of the war, you would think that this interest would diminish. But actually, we see that the interest, also among the younger generations, is increasing, which is, of course, a very helpful sign. What we do see in terms of changes is that younger generations know less about the Holocaust. There is less and less time or attention to Holocaust education in schools in many countries. We need to rethink how to present the memory of the Holocaust in the 21st century.

Jane L. Levere is a New York-based freelance journalist and contributor to The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN and Forbes.com, among many publications. She is also a life member of Hadassah.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply