Arts

Unearthing Hungarian Heroism and Discovering Jewish Roots

When Linda Ambrus Broenniman opened the battered cardboard box she had received from her sister, it started her years-long research into her Jewish roots. The box, filled with black-and-white photographs, letters and documents in Hungarian and German, was one of the few items that survived a devastating 2011 fire that had claimed their mother’s life, injured their father and damaged their parents’ home in Buffalo, N.Y.

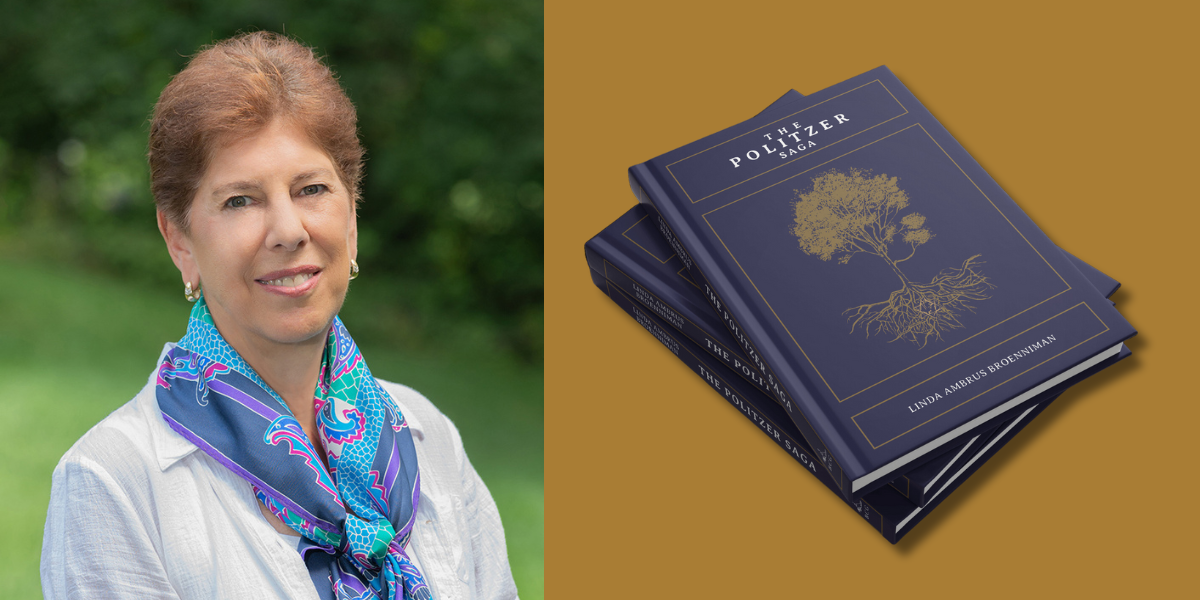

“My quest for the truth about my family began at that moment,” Broenniman writes in The Politzer Saga, her 2023 book chronicling her family history.

The book wasn’t the only creative pursuit begun at that moment. Broenniman’s research has also led to a permanent exhibition at a magnificent restored synagogue in Budapest. And last May, a mural with an image of her mother was unveiled in Buffalo, pointing to another aspect of her family’s story.

The box had been hidden in her parents’ attic for decades. In addition to records of her father and other relatives, it contained a composition book with the words “Our Family Tree” on the cover—a handwritten account by Broenniman’s paternal great-great-uncle, Hungarian journalist Zsigmond Politzer.

It also held answers to questions, Broenniman explained in an interview, that she had been asking her parents, Drs. Julian and Clara Ambrus, for years. She and her six siblings were raised Catholic. Growing up, they knew little of their Hungarian-born parents’ pasts, other than their immigration to the United States in 1949.

Through a chance remark by her sister’s godmother in the late 1980s, when Broenniman was 27, she found out that her father was born Jewish. Though Broenniman sought more details, her father deflected her questions, maintaining a web of silence around his life in Hungary.

Among the information her parents had kept from her: Julian was a descendant of a storied Jewish Hungarian family; he had escaped from a Nazi labor camp; and Clara had hidden him during World War II.

“Discovering my Jewish heritage has been a profound gift, and I feel deeply honored and proud to be a part of this rich lineage,” she said, adding, “While I hold immense respect for Judaism and its traditions, I’ve realized that my spiritual path lies outside of organized religion.”

Her parents were young medical school students in Budapest and engaged to be married when the Nazis occupied Hungary. Through research, Broenniman found out that her father, who already had converted to Catholicism, was taken to a forced labor camp in the spring of 1944. After his escape, he returned to Budapest and reunited with Clara. Then only 19, she helped hide a group of around 20 Jews, including Julian and his mother, in an abandoned factory, where they spent the remaining months of the war.

Broenniman only discovered her mother’s heroism in 2006 when Clara was honored as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. One of the women she had saved from the Nazis had recommended her for the distinction.

Her father gave the acceptance speech at the ceremony at Yad Vashem for his wife, who by that time was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Even in his speech, he omitted that he had been one of those with Jewish heritage whom she had saved.

After the ceremony, Broenniman recalled, she once again approached her parents with questions about their past. Her father still refused to answer, and her mother could no longer respond. In a moment of clarity, however, she told her daughter that there had been a box with documents that held answers.

Using the information found in the box and with the help of Andras Gyekiczki, a Hungarian sociologist and genealogist, Broenniman traced her Hungarian Jewish lineage through the Politzers, back eight generations to the 1700s. They learned of her accomplished ancestors, including physician Adam Politzer, who was considered a trailblazer in the field of otology and had treated Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria and King Leopold II of Belgium, and celebrated lawyer Ignacz Misner, founder of the Budapest Bar Association, who had tried to save his family from the Nazis but died in the Budapest ghetto.

“When I began learning not only about my ancestors, but what my father had gone through, I started to understand him,” Broenniman said. “I think he faced such trauma and never really dealt with it,” she added of her father, who passed away in 2020. “I think I can forgive him for that.”

Before Gyekiczki also passed away in 2020, he connected Broenniman with the Rumbach Street Synagogue, located in Budapest’s historic old town. Her ancestor journalist Zsigmond Politzer was a member and had purchased permanent seats at the synagogue. Built in 1872 in the Moorish Revival style, the building was damaged during World War II but later restored and reopened in 2021 as a cultural and religious center.

As part of its reopening, the synagogue had sought a family story that could reflect the complex history of Hungarian Jewry for a multimedia exhibition space on the third floor—and Gyekiczki had wondered if the Politzers might be a good fit.

“The Politzer Saga,” the institution’s new permanent exhibit, features 10 short films—featuring archival clips, animation and contemporary interviews—and other displays that explore Hungarian Jewish life beginning in the 18th century through the life of the Politzers. One of the films tells the story of Eisik, the earliest ancestor to whom Broenniman was able to trace her Jewish lineage, a violinist from a village called Politz who had to flee religious persecution. Eisik’s son, Moishe, became a doctor to Hungarian aristocrats and had 10 children.

“Here were the people who were so incredible and had such traumatic experiences,” Broenniman said. “And I felt they had died twice. In their natural lives and because their names were hidden.”

Meanwhile, with the May 2024 unveiling of the mural in Buffalo, public recognition of her mother’s heroism is on display, thanks to the Righteous Among the Nations Global Mural Project, under the aegis of Artists4Israel, and the Buffalo Jewish Federation, which raised the funds and brought together the families and the organizations to collaborate on the mural’s production. The mural, painted by Hungarian street artist TakerOne, adorns a building in the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center hospital complex and features black-and-white portraits of Clara and two other Hungarian non-Jews, Tibor Baranski and Sister Margit Slachta, who saved Jews during the Holocaust. All three had immigrated to the United States, made their home in Buffalo and have a personal connection to Roswell.

“We believe that by celebrating the heroism of those who stood up against antisemitism, we not only honor those heroes but create a model for behavior in the face of Jew hatred,” Craig Dershowitz, CEO of Artists4Israel, said. “We were proud to partner with the community in Buffalo to bring this project to their wonderful city and to share with hundreds of people a day a story about how we can protect Jewish lives even in the face of danger.”

Alexandra Lapkin Schwank is a freelance writer for several Jewish publications. She lives with her family in the Boston area.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply