Being Jewish

The Last Generation of Holocaust Survivors

In the late 1990s, writing for a New York City Jewish newspaper, I spent many afternoons on plastic-covered sofas while interviewing Holocaust survivors over cake and coffee. My European-born subjects, then in their 70s and 80s, had largely been adults with families during the war. They had made wrenching decisions in order to save their children and had witnessed the unthinkable in concentration camps.

Their survival stories had the quality of action thrillers: Nazi chases, forest hideouts, daring escapes from moving trains.

Today, virtually all the survivors of that generation are gone—including such high-profile figures as Ruth Westheimer, the German-born sex therapist known as Dr. Ruth who died last July, and the Hungarian-born British memoirist Lily Ebert, who had two million followers on TikTok and passed away in October. Those still alive who bore witness to the Holocaust were, for the most part, children during the war, with the diffuse and impressionistic memories of youth. While their parents were forced to make agonizing choices for them, as children they lacked agency, living out those decisions amid a dystopia of lost families, ruptured friendships, seized homes and untimely lessons in human cruelty.

As I got to know some of these “younger” female survivors in the United States—octogenarians and nonagenarians speaking 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz—I noticed common threads. Their families, not especially religious, had been well integrated into their European communities. Many, likely due to the disruption and instability of war, had no siblings. As adults, they seemed more American than their parents’ generation, perhaps because they had moved to the United States while still quite young.

Their wartime experiences were shaped by displacement and hiding, rather than camps like Auschwitz, which few young children survived. Over and over, I heard about the cruelty of strangers: The classmates who beat up Jews, the neighbors who attacked without provocation and even the Russians who treated the Jews they liberated with callous dehumanization.

These women see echoes of that cruelty today, as antisemitism flares up in the country of their refuge and around the world. And to a one, they emphasized the vital importance of Israel to Jewish survival. Here are the stories of five women who survived the Shoah—and their reflections on life as American Jews today.

Ronnie Breslow

At a Kristallnacht commemoration at Or Hadash Synagogue in suburban Philadelphia, Ronnie Breslow tells the congregation of her first, heartbreaking voyage to the Americas at age 9. It was aboard the infamous St. Louis, a ship carrying 1,000 refugees, most of them Jewish, that was refused dockage first by the Cuban authorities, then by the United States government, before being turned back to Nazi Europe in 1939.

“We saw the shimmering lights of Miami Beach; that’s how close we came to America,” Breslow, now 94, tells her audience. Just days after the world was shaken by an Amsterdam pogrom last November targeting visiting Israeli soccer fans, Breslow speaks of how impressed she was that Israel chartered planes to rescue its stranded countrymen. “In 1938, we didn’t have an Israel to go to,” she says. “We were stuck.”

It is a lesson, more than any other, that the Stuttgart-born Breslow impresses on her audiences. She has done so ever since the 1970s, when she began speaking about her experiences.

In her appearances, now arranged through the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center in suburban Philadelphia, she relates how her family—with roots going back five centuries in southern Germany—saw its comfortable world disintegrate after Hitler passed the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws. Her first-grade teacher told her not to come back to school, her best friend was beaten for associating with a Jew, and Nazi guards discouraged shoppers outside the family’s dry goods store.

When her father had the opportunity to escape Germany solo, her mother insisted he go, arguing the family had better odds with one person abroad. She was right. He made it to the safety of Cuba, and although their planned reunion on the island was foiled, the family eventually reconvened in New York City in 1949 thanks to her father, who had migrated from Cuba to America and sponsored the family. In between, Breslow—then Renate Reutlinger—and her mother survived thanks to the brave decision of the captain of the St. Louis to defy German orders to return home, landing instead at Antwerp.

The ship’s plight—they were stranded in international waters for more than a month—garnered international attention, and Dutch onlookers clapped for the refugees from the shore. Still, their fortuitous survival involved months of isolation and deprivation in a Dutch detention camp.

Breslow still has the thoughtful dark eyes of the bob-haired girl pictured on both her German passport and her American immigration card. While her family’s arrival seemed like a happy ending, the survivor recalls a difficult new beginning when the family settled in Philadelphia. Poorly dressed, unable to speak English and with chronic eye infections, Breslow struggled in school while her parents struggled to earn a living.

At 19, she married a fellow German refugee, Paul Breslow, though they never discussed their past. There were happy years, as they both worked in medical laboratories, but also tragedy: Of Breslow’s five children, only three survive.

With antisemitism rising globally, she has a warning. “I see history repeating itself,” Breslow tells the crowd. Addressing a row of children, the grandmother of nine and great-grandmother of five adds: “I, too, had a normal childhood…. The big difference between then and now is we have the State of Israel.

“I caution all of you here today to be careful,” she continues. “Don’t lose this very precious gift, freedom. God bless America and God bless Israel.”

Gabriella Karin

In her Los Angeles studio, Gabriella Karin shapes copper and clay into wrenching images of suffering. The contorted figures and outstretched hands evoke a childhood warped by Nazi terror in her native Bratislava, where Lubitsa Gabrielle Foldes, as she was called then, enjoyed a carefree childhood until 1938.

That was when the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia—and seized the Foldes family’s apartment. After unsuccessfully trying to send their daughter to safety abroad, her parents obtained false papers and placed her, then 8, in a convent boarding school.

“I cried myself to sleep every night,” recalls Karin, 94, who in America adopted her middle name. “A year later, my mother came to visit, and when she saw my cried-out eyes, she decided to take me.”

After moving from one hiding place to another, the extended family—eight people—was taken in by a non-Jewish lawyer. Somehow, the Nazis never suspected their presence in the district’s only residential house built, according to Karin, under a 1935 law that prohibited Jews from occupancy,

“The lawyer brought us food, but he couldn’t bring too much,” in order to evade suspicion, explains Karin. “We were hungry all the time. And he brought me books to keep me quiet, but they weren’t books for young girls.” Instead of going to school, young Lubitsa made do with Dostoevsky and Tolstoy until the Russian liberation, when the family reclaimed their store, a delicatessen.

After studying fashion in Bratislava, at 19, Karin and her husband, Ofer Karin, a fellow survivor, decided to move to Israel; reluctantly, her parents followed their only child. As a dressmaker in Netanya, “I had a good social life,” Karin says. “We were all survivors, and we never knew each other’s stories. We never talked about it.”

In 1960, after her mother visited the United States and declared it “a much easier life” than Israel, Karin and her family, including her parents, resettled in Southern California, where they found yet another community of European refugees. There, Karin worked as a fashion designer for department stores and raised a son.

Years later, Karin began to speak out; she now shares her story of surviving the Holocaust regularly with local audiences through Los Angeles’s Museum of Tolerance and other organizations. In retirement, she says, she took up sculpture, which she exhibits locally, “so people can see visually something, not only the written word. It brings them closer” to the Holocaust experience.

And she marvels that as a Jew in America, she has felt that she is an equal citizen—unlike her father in Bratislava who, though a proud Czech, was rejected from the army for being Jewish. Lately, though, Karin worries about authoritarian rhetoric from some of the country’s new top leaders.

But Karin, who has two living grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, says she is determined “to not dwell on things.”

Repeating the vow she had made after witnessing her unrecognizably skeletal neighbors returning to Czechoslovakia in 1945, Karin stresses, “Hitler will never get my body, my soul. Be happy; don’t be a sad person. Otherwise, he has won.”

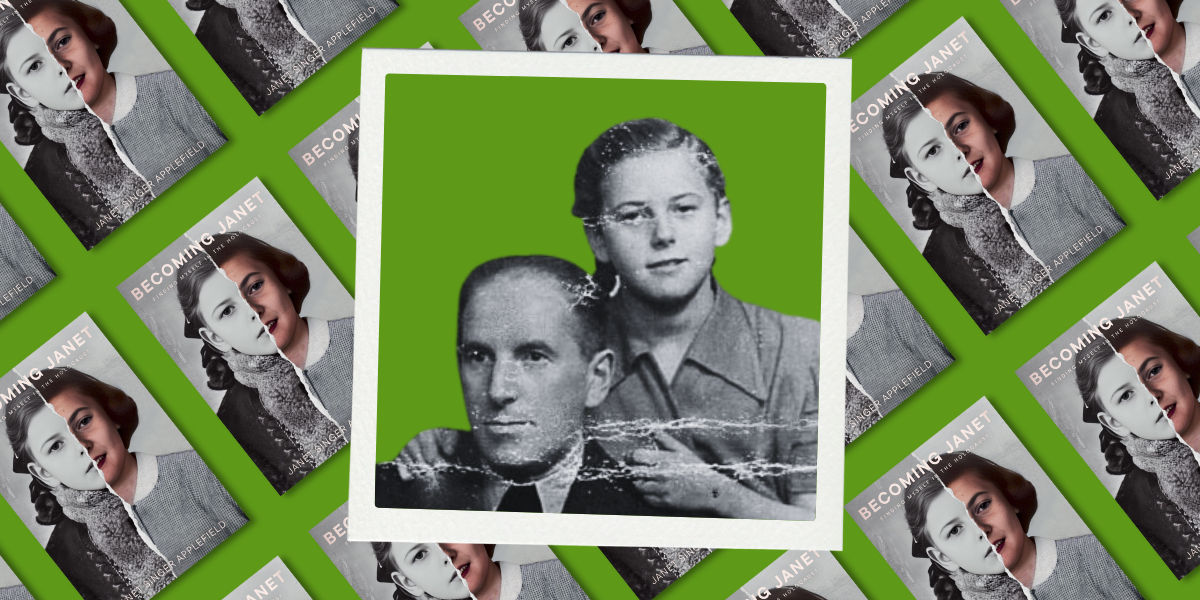

Janet Applefield

For a long time, Janet Applefield declined to share with the world her story of how she survived the Holocaust—of fleeing to Ukraine on a wagon as the Nazis invaded her native Poland, seeing cousins sent to the Siberian gulag, hiding from German soldiers in a potato field, losing a baby sister to diphtheria.

And that was only the first chapter, before Gustawa Singer, as she was then named, went into hiding at age 7, spending three years alone and on the run before ending up in a Jewish orphanage. “I didn’t think that my story was valuable because I never considered myself a survivor—I’d never been in a camp,” says Applefield, 89. But when other hidden children began speaking out in the 1980s, the Boston-area social worker decided it was her responsibility to speak up about what she’d witnessed.

Applefield now shares her story with 4,000 people annually, mostly through the Boston-based nonprofit Facing History & Ourselves, whose grade-school curricula teach racial and ethnic understanding. In 2021, she spoke before the Massachusetts State Legislature to champion mandatory public school genocide education. And in 2024, Cypress Books published her memoir, Becoming Janet, based on postwar notes her father wrote of her experiences. (After setting it down on paper, they never spoke of it again.)

“I’m very upset about what’s happening in the world and how much hatred there is toward Jews,” Applefield explains of her continued motivation to speak out. “This Middle East situation and the Ukrainian war—it really triggers me and frightens me terribly.”

Having started out as the “pampered and spoiled first grandchild” of a well-to-do Krakow-area Jewish family, Applefield knows how quickly things can change. She remembers cooking for Jewish holidays alongside her mother and grandmother, and riding an uncle’s sidecar to the candy store. That life ended when the family was awakened on September 1, 1939, by sounds of the Nazi invasion.

Taking the identity of a dead Polish girl, she was handed over to a family friend. Applefield’s father was eventually arrested and selected for slave labor. Her mother and grandmother, unable to outrun the Gestapo, perished in a death camp.

Applefield sought shelter with various non-Jews, enduring beatings and Gestapo raids until she was able to escape to Ukraine. She was finally liberated back into a postwar Poland aflame with antisemitism, where hospitals wouldn’t treat Jews—she was crippled by rickets—and her orphanage was repeatedly attacked by torch-bearing Polish horsemen.

Applefield was lucky to be reunited with her father by the resourceful orphanage director. But she shrank at first from the skeletal stranger and was reluctant to leave her fellow orphans. Father and daughter returned to their war-ravaged hometown, but it “had lost its life and color,” she recalls. And it remained unsafe: After several Jewish friends were murdered and her family was threatened, Applefield’s father began sleeping with a gun.

Two years later, her father secured a medical visa to the United States and hastily married a Jewish American acquaintance to gain permanent residency. While he started a hardware business in Newark, N.J., Applefield, then a teenager going by Janet, struggled to learn English and catch up on years of missed school.

She married while still in college, waiting decades before divorcing her abusive husband out of fear that she’d lose her three children—the kind of family separation she was determined not to perpetuate. “I had a crazy life,” reflects Applefield, now a grandmother of five. “But you know, I survived.”

Marion Kreith

Born in Weimar-era Hamburg, Marion Kreith was a wartime refugee in Brussels, worked for several years as a teenager in Cuba’s diamond-polishing industry and came of age in Los Angeles. She has seen enough war, hatred and displacement to be “very scared for what may happen to us here,” says Kreith, referring to the rise of both antisemitism and populism in this country.

“But I’m more scared about what’s happening to Israel, because it was the creation of the State of Israel that gave Jews in the world a bit of standing for all those years. Now that feeling of safety is being fractured,” she says, referring to the recent wars in Gaza and Lebanon.

Kreith, 97, was born to a secular German-speaking family, the Finkels, who owned a dry goods store. Her childhood was “physically very comfortable, but emotionally very scary,” Kreith recalls. By 1933, Jewish children were banned from public school and no longer allowed to play with non-Jewish friends. Walking outside, “you never knew if you were going to get stoned at or jeered at by German kids.”

Worried about supporting his family during the Depression, Kreith’s father opted against immigration to America. But after Kristallnacht in 1938, the family decamped to an uncle’s house in Brussels, where Kreith learned French in school. When the Nazis invaded in 1940—“in the mornings, you heard them goose-stepping”—her father was taken away.

After discovering that her husband was in a camp in southern France, Kreith’s mother took Kreith and her sister to Antwerp and arranged covert passage to Marseille, where they survived for months on the only food available—tomatoes and onions—cooked on a hotel-room hot plate. Somehow, Kreith’s mother negotiated French exit visas, transit visas through civil war-ravaged Spain and Portugal and passage from Lisbon to Cuba for the whole family, including her father. They landed in Havana in 1941.

What the family anticipated as a brief stay in Cuba turned into a five-year wait after the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor halted immigration into America. The burgeoning diamond industry in Cuba sustained Kreith’s family as well as a generation of European refugees, who communicated in a mix of English, Flemish, Spanish, French, German and Yiddish.

After another uncle sponsored their passage to Atlantic City, N.J, in 1946, yet a third uncle offered them an apartment in Hollywood, Calif., where they settled.

At the age of 24, Kreith married a fellow survivor, Frank Kreith—a Viennese Jew who had survived thanks to the Kindertransport children’s refugee program—and started a happy life together in Boulder, Colo. There, her husband became a college professor of mechanical engineering while she taught grade-school French.

They had three children, to whom Kreith regretfully admits she didn’t speak enough about the Holocaust. In fact, she only recently started speaking about it at all—sharing her story with Boulder audiences after her daughter, Judy Kreith, made a documentary film about Jewish participation in Cuba’s diamond industry called Cuba’s Forgotten Jewels: A Haven in Havana.

Her reticence perhaps comes from a childhood “living with an awareness of otherness,” says Kreith, who has three grandchildren. “Jewishness is not really a part of our life. It is very strongly a part of my heart. But I suppose my German experience keeps me lying low at all times.”

Miriam Schupacheveci

The happiest years of Miriam Schupacheveci’s life were as a young wife and mother in Israel, rebuilding her life after the war. “Everybody was newcomers. We had nothing,” says Schupacheveci, recalling how she and other Holocaust refugees would pop in and out of each other’s Haifa apartments, their kids mingling while the adults drank coffee. “But it was a happy life.”

Israel, where one of her three children and four of her nine grandchildren still live, remains a touchstone for the 89-year-old Schupacheveci. The Jewish state felt like an extended family, a balm after the Holocaust. Her suburban life in Philadelphia, where she has lived in the same house since resettling in the 1980s, “is very different,” she reflects. “But America was my husband’s dream from the day I married him.”

Born Marieta Markovic in Romania, Schupacheveci grew up in a small town near the Russian border, the only child of a shoe leather tanner and a mother whose pharmacist ambitions were derailed by antisemitism. One of Schupacheveci’s earliest memories, from January 1941, was the Nazi evacuation of local Jews to the nearby city of Iasi.

“The trains arrived full of people; they were suffocating,” she says. “My mother offered water at the station and got beaten by the Germans.”

Soon enough, Schupacheveci’s own family was part of that transport, living on bread and tea in a makeshift Iasi ghetto while her father was put to work at a factory making boots for German soldiers.

In 1944, her beloved father was killed while protecting Schupacheveci during an air raid. While still in Romania, “I used to say to my mother to take me to his grave every day,” she recalls.

Thirty years later, when she returned to her native country, “I went straight to the grave.”

Though she doesn’t remember all the details, Schupacheveci says she and her mother survived the war moving between relatives’ houses, then marked time in Bucharest until securing passage to Haifa in 1950. In Israel, they reunited with her mother’s six siblings. She finished high school, married at 18—to a Polish Jew, Mordhai Schupacheveci, his family’s sole survivor—and became a knitwear designer.

It was a career she continued in Philadelphia, where she opened a yarn shop. Her husband became a shoe repairman, a kind of homage to the father-in-law he never knew.

Schupacheveci still volunteers at the kitchen of her local Jewish community center, serving patrons who are mostly refugees from the Soviet Union. Close by in New Jersey are two grown children and their families.

“I don’t leave a nice world for them. That’s my big problem,” reflects Schupacheveci, as the conversation turns to the wars Israel has been fighting and rising antisemitism. “History is repeating itself.”

At least “we have Israel behind us,” she adds. “As a Jew, if you don’t have Israel behind you, you cannot exist anywhere.”

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Debra Breslow says

Great article-

Paquita Sitzer says

Outstanding report of the lives of in spite iof hardships fortunate survivors. With a very realistic attitude. One sad comment. We are not leaving a pretty world for our heirs. We want to be optimistic and we are thanks to Israel and it’s citizens. Am Israel Jai.

siva heimanl says

I don’t agree with Kink Bibi. I agree with the millions of Isrealis who want justice for all.

Siva

Teresa Fleener says

Why? Why? Will humanity not learn from history? Just as we are seeing anti-sematism from lack of education, it has extended to anti-science from lack of teaching in the public schools. Thank you, ladies for sharing. Let us continue to demand thorough educations for our youth so they will know and will not forget.